Few people have heard of Eliza Fenning today, but in 1815 she was the most famous wronged woman in England. Executed for a crime on flimsy evidence, she inspired a new age of scientific inquiry — and a character in Frankenstein.

When Mary Shelley wrote Frankenstein in 1816, she included a character based on the defendant in a famous murder trial. The monster comes after Frankenstein’s family and murders his brother, William. A locket is planted in the pocket of Justine, the family’s nanny, and she’s soon executed for a crime she did not commit. The actual “Justine” was Eliza Fenning, a 20-year-old maid who had been put to death just the year before for an attempted murder. We don’t know if she actually tried to kill anyone or not, but even then everyone knew that the justice system hadn’t sufficiently made its case.

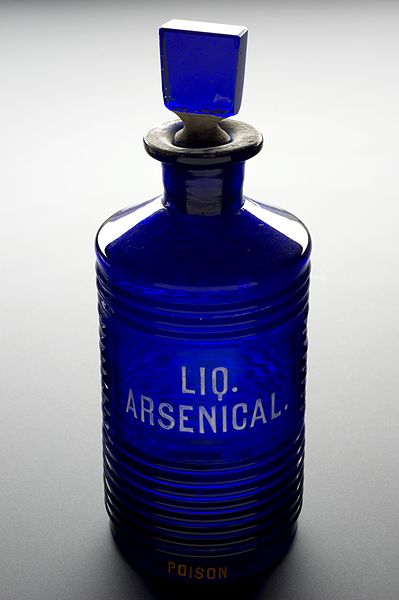

Things looked bad for Eliza from the start. The family she worked for as a cook had eaten her dumplings and promptly fallen ill with what even to modern eyes looks like arsenic poisoning. Several witnesses testified that she disliked the family in general, and the mistress of the family in particular. A few weeks before the incident, a packet of arsenic had gone missing from the house.

Things went from bad to worse when experts on arsenic got involved. The star of the trial was an expert witness called John Marshall. He was already suspicious when he arrived at the kitchen to investigate the crime, because he’d heard that the dumplings had failed to rise properly. Everyone knew that arsenic kept bread from rising. When he burned the half-teaspoon of carefully-reconstituted powder from Eliza’s mixing bowl, as well as slices of dumpling, he smelled garlic. Arsenous oxide smells of garlic. Finally, the knives that he had used to slice the dumplings had turned black — a sure sign, he said, of arsenic.

Eliza was hanged. She proclaimed innocence to everyone who would listen, including the priest on the scaffold with her. Soon doubts over the facts of the case cropped up. Arsenous oxide does smell of garlic, but the “garlic test” as it was known, is subjective, and Marshall was conducting it in a kitchen. The amount of supposed arsenic he found in the mixing bowl was so great that, if a proportional amount had been put in the dumplings, the entire family would certainly have died. (And Eliza along with them. She had eaten the dumplings, too, and gotten a mild case of poisoning.)

Gordon Smith, a professor of forensics, came up with the most spectacular test for arsenic — and one that if it had been performed earlier might have saved Eliza’s life. He got a box of arsenic and a box of pickled walnuts. Putting identical knives in each for ten hours, he withdrew the knives to show that the walnut knife was tarnished, and the arsenic knife was utterly undamaged.

Eliza’s case helped launch an era that valued concrete and repeatable tests done by experienced experts. It also launched experiments on yeast and arsenic that continue to this day. It’s doubtful that either of those facts would be much comfort to her.