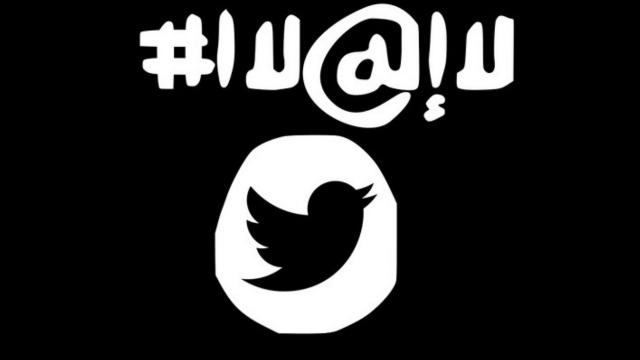

With all the handwringing over how ISIS is “winning” on social media, recruiting young people using Facebook, Twitter and YouTube, one policy wonk thinks we should fight back. He’s got disturbingly detailed plans for how the US government could borrow troll strategies to defeat ISIS on the internet.

New Jersey senator Cory Booker once noted that ISIS has “fancy memes” — so why shouldn’t we get some weaponised memes of our own? That’s what Kalev H. Leetaru believes. He’s a senior fellow at the George Washington University Center for Cyber and Homeland Security and a council member of the World Economic Forum Global Agenda Council on the Future of Government. And he’s written an article for Foreign Policy about how we could run a great psychological ops campaign against ISIS.

He begins by pointing out that the US is focusing all its efforts on censoring ISIS accounts, a strategy that has been proven not to work. We should, he argues, learn from China and Russia that censorship isn’t enough. Instead, the government has to engage actively in misdirection, propaganda, and abuse.

Leetaru writes:

China and Russia learned long ago that simply censoring objectionable material does not work. Instead, the United States could flood the online environment with an overwhelming volume of counter-narratives that simply drown out all other voices. The Chinese propaganda machine, for instance, employs over 300,000 people, including over a quarter-milliononline commentators, whose job is to saturate the web with Beijing-friendly material, while encouraging self-censorship through high-volume character attacks against users posting objectionable material. Russia employs a similar model to control domestic Internet conversation. It adds an offensive element, via propaganda campaigns that spread panic-inciting, false reports of industrial accidents, pandemic outbreaks, and other calamities across the United States.

Imagine if we used a similar approach against the Islamic State. Each time Twitter suspended one of its accounts — let’s use the fictitious @ISISSupporter as an example — the U.S. government could register a thousand new ones, using every conceivable variation of the original user name, designed to appear identical to the suspended account, with handles like @ISISSupporter2, @ISISSupporter3, @SupporterOfISIS, and so on. Each account would claim to be the true reincarnation of the original.

When the real Islamic State user finally registers a new account, the U.S.-registered accounts would go on the offensive, tweeting claims that the real account is a phony designed to ensnare sympathizers. Other accounts would be set up to look like official Islamic State recruiter accounts, posting genuine Islamic State material. But the “recruiters” operating those accounts would, in reality, be government agents lurking in encrypted chat rooms, sending links that redirect the user’s browser to location-tracing malware.

In conjunction, U.S. cyber warriors would upload hundreds of thousands of videos to YouTube and similar platforms. The first few seconds would be lifted from an Islamic State video to ensure that their thumbnail and preview appear legitimate, while the rest would present a counter narrative or be blank. Links to these fake videos would be tweeted in the same fashion that the Islamic State tweets its own videos, effectively drowning legitimate videos in a sea of fake ones. Simultaneously, every Twitter hashtag and meme posted by the Islamic State would be met with a barrage of tens of millions of counter messages, crowding out pro-Islamic State sentiments. A non-stop barrage of false messages would post claims of battlefield failures, defections, and drone strikes, overwhelming positive news and inciting local panic. The end result would be an environment where would-be Islamic State supporters and fighters could no longer distinguish between what was real and what was illusion, or who and what to trust — “a wilderness of mirrors,” to borrow the words of the former head of U.S. counterintelligence.

This is so intensely detailed that I get the feeling I’m reading psyops fanfic, or maybe an NSA proposal that got shot down. Still, this really could be the future of psychological warfare. The problem is — where do you stop? Once we’ve started emulating China by creating a “wilderness of mirrors” on social media to defeat ISIS, will we start to see a widespread acceptance of the practice?

Anti-gay churches could create fake “homosexual” accounts where prominent gay leaders talk about how much they love pedophilia. Presidential campaigns could create fake accounts for their opponents, which post racist jokes. Oil companies could pretend to be environmental advocates online, smearing the reputations of environmentalists and community activists.

Once you create an environment where it’s acceptable weaponize memes, anyone can use them. Maybe the solution to bad speech isn’t always more speech, especially when what you mean by “more speech” is really “more lies.”