Two weeks ago, Nobel-prize winning cell biologist Tim Hunt created a storm of controversy when he made a comment about how he can’t work with women because he always falls in love with them, or they with him. But why does he think love in the lab is such a problem? Here are four stories of couples who met through science, fell in love, and created a productive scientific collaboration — though not necessarily in that order.

Being in love doesn’t stop a couple from doing research independently. It doesn’t affect the quality of their studies. And anyone who thinks a couple won’t criticise one another’s ideas needs to get out more.

Sometimes, scientist couples even collaborate on a shared project. And like any good scientific collaboration, these couples take advantage of the strengths each partner brings to the table. One may be a better experimentalist, the other may enjoy theory more — but they combine their talents and help one another produce work that is better than either person could do alone.

Physical Chemistry: Jerome and Isabella (Lugoski) Karle

Jerome Karle and Isabella Lugoski met in their first physical chemistry class at the University of Michigan in 1940. He was in his first year of doctoral work, she was in her last year as an undergraduate, and the magic of alphabetical order made them lab partners. They didn’t hit it off at first.

I walked into the physical chemistry laboratory and there’s a young man in the desk next to mine with his apparatus all set up running his experiment. I don’t think I was very polite about it. I asked him how did he get in here early and have everything all set up. He didn’t like that. So we didn’t talk to each other for a while.

Their relationship got going as they competed for the top grade in that course and they bonded over their mutual interest in chemistry. They married in 1942. By 1946, both of the Karles had earned doctorates in physical chemistry, and, after a stint at the University of Chicago working on the Manhattan Project, moved to Washington DC to join the US Naval Research Laboratory.

Each specialised in a different aspect of X-ray crystallography: Jerome focused on developing equations that could determine how atoms were arranged inside complex molecules, while Isabella ran practical experiments to test how well the equations worked. Working together, they created what is now called the direct method for determining molecular structures, which has allowed scientists to efficiently study and duplicate complex organic molecules to develop new fuels, heart drugs, antibiotics, antimalarials, and antitoxins.

Jerome Karle was awarded the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1985. Although he was disappointed that the Nobel committee had ignored Isabella’s contribution to that work, she was unfazed. At that point, she had already won more awards and prize money for her experimental work than he had.

Animal Behaviour: Steve Nowicki and Susan Peters

By the time Steve Nowicki arrived at Peter Marler’s birdsong lab in 1984, Susan Peters had been a research associate at the Rockefeller University’s Center for Field Research for a decade. Nowicki knew her by reputation, a “really brilliant scientist who had written really important papers” on how young birds learned adult songs. Peters was also impressed by Nowicki’s work on the physics of song production: “I thought it was the best talk I ever heard.”

The two soon became close friends, running together during lunch, sharing their interests in nature, and commiserating about their unsuccessful love lives. Eventually, Peters told me, she realised Nowicki “was far more interesting than anyone else I had ever dated.” They were married in 1986. But they didn’t start collaborating scientifically until they moved to Duke University in 1989.

Nowicki and Peters have now written more than 30 papers together, exploring how young birds learn to control their bodies as they sing, how song learning is affected by stress in infancy, and whether a male’s song can give a female hints about how good he is at foraging or avoiding predators. They both stress that their complimentary talents are what make their scientific collaboration a success. Says Peters, “I think one reason we work so well together is that we bring different things to the table.” Peters is the experimentalist: she loves designing experiments, collecting data, and analysing it. Nowicki is best at synthesis: looking for patterns that help knit different datasets into a larger story. They encourage and challenge each other, and, says Nowicki, “I think the synergy makes the science that much better.”

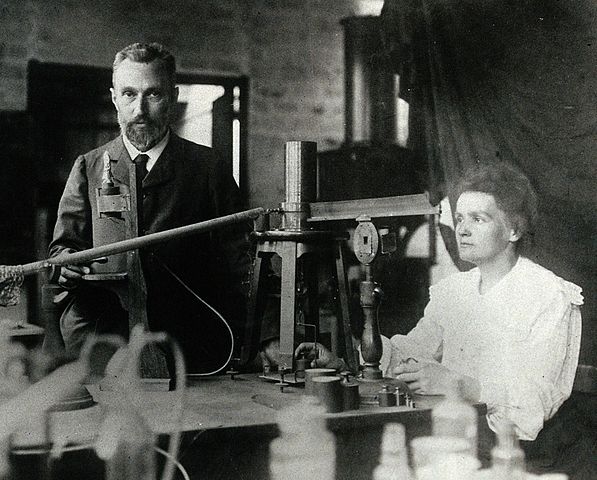

Physics: Pierre Curie and Marie (Sklodowska) Curie

In 1894, Marie Sklodowska was looking for a laboratory in Paris that would give her enough space to let her continue her work on magnetism. A friend pointed her to one of France’s foremost experts in the field, expecting that he might be able to help her. Unfortunately, Pierre Curie didn’t actually have any space of his own — he was running experiments in a closet shoved between a hallway and the student laboratory where he worked as an instructor.

But Pierre was willing to help Marie use a highly sensitive piezoelectric instrument he’d invented in her work. And although he’d once written that women were nothing but a distraction to scientific work, Pierre was entranced by Sklodowska and their shared interest in both science and humanitarian causes. They married in 1895.

After their honeymoon, Pierre continued to investigate the electrical properties of crystals while Marie started doctoral work on radioactive elements. By the middle of 1898, Pierre decided that Marie’s work was far more interesting than his, and dropped crystals altogether to join her experiments on radioactivity. They worked as a team: Pierre concentrated on defining the properties of the elements, Marie developed techniques to purify them. Their collaboration identified both polonium and radium, and jumpstarted an industry built around radium salts.

The Curies shared the 1903 Nobel Prize in Physics with Henri Becquerel. Pierre died in a streetcar accident in 1906.

Neuroscience: Stephen Macknik and Susana Martinez-Conde

Stephen Macknik and Susana Martinez-Conde were scientific collaborators for years before they even considered dating. Now neuroscientists at SUNY Downstate Medical Center, the two met as postdoctoral associates in David Hubel’s lab at Harvard Medical School in 1997 and spent the next five years examining aspects of perception in the visual cortex. Their joint projects were successful — so much so that when both Macknik and Martinez-Conde were offered jobs at University College, London in 2001, they took them for the sake of the collaboration.

The two had become good friends, and as they started assembling their new labs they continued to spend a lot of time together. In 2002, Macknik suggested that they try dating. Martinez-Conde told me that she was sceptical.

I thought it was a terrible idea, because I thought, “We have such a good working relationship — is it worth it to jeopardize it? If things go sour, what’s going to happen to the collaboration?” It was a complicated decision for both of us.

Macknik must have been convincing. They were engaged three months later.

Today, Macknik and Martinez-Conde still keep collaborations going between their two lab groups. They have made major discoveries about visual perception, including the role of eye movements and how the brain perceives the brightness of light. They’re well-known for joint work on illusions and how magic performances fool the brain, the subject of both their popular science book Sleights of Mind, and a column at Scientific American. But, says Martinez-Conde: “We like each other’s science, and that’s at the heart of our relationship.”

[US Naval Research Laboratory | Atomic Heritage Foundation | American Institute of Physics | Goldsmith 2005]

Pictures: Tara Jacoby; Jerome and Isabella Karle, via US Naval Research Laboratory; Steve Nowicki; Wikimedia; Stephen Macknink