It might seem like all of California is busy naming scapegoats who consume unfair shares of water during the state’s historic drought. But there’s actually no way for the public to go after the state’s worst water wasters because there’s no way of knowing who they are. Legislation has ensured that much of the state’s water data will never be made public.

In fact, California is the only state in the west that does not make its water data public.

While the state has promised to call out cities with exceptionally high per capita water usage — information which was only released by the state for the first time last year — that’s one small part of the water data story. Due to several measures that challenge open government policies, what should be boundless flows of open data about our most squandered resource are as dry as the wells in much of the state. And right now California needs all the data it can get — not only to find out who the biggest water hogs are, but so data scientists, visualisation designers, developers, and engineers can work together to find better and more relevant ways for the state’s residents to weather the drought.

Protecting water wasters

When the California Public Records Act was passed in 1968 it was one of the most progressive public information efforts in the country. It’s easy, for example, to find water information collected by the state at public monitoring stations. But several challenges to the act have removed more specific datasets from public access. An intriguing story at Reveal uncovers a 1997 measure that was specifically written to keep water consumption data in the dark. And it was brought about specifically so affluent tech industry giants would not be forced to reveal their own water use.

The city of Palo Alto was the first to back the measure, which was sponsored by its former mayor Byron Sher. As a state senator, Sher had helped pass several important environmental initiatives like the Groundwater Protection Act. But this 1997 legislation he introduced was not so much about protecting underground aquifers as it was about protecting Intel execs, since many of the state’s wealthiest residents lived in Sher’s Silicon Valley district.

Releasing personal information about water and energy usage was a safety issue, argued the supporters, citing a 1989 case where the man who murdered actress Rebecca Schaeffer legally got her information from DMV records.

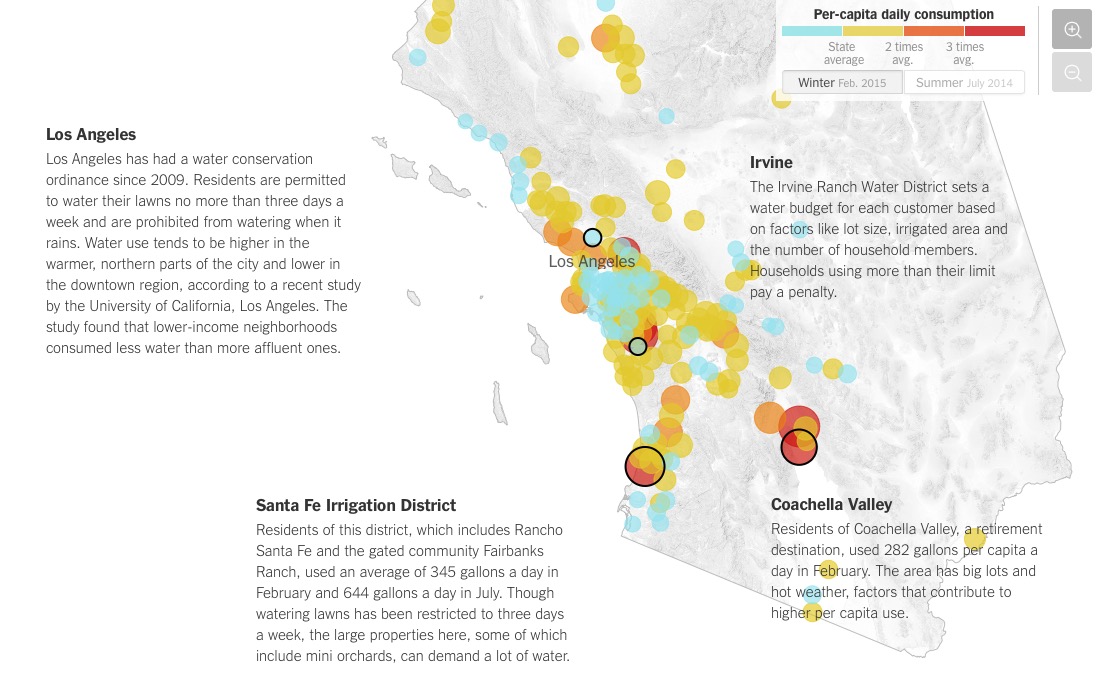

A detail of an infographic by the New York Times showing municipal water use in California. While cities report aggregate data, the available information is usually not much more granular than that.

The problems with California and water data go even further back than that, according to a story in Government Technology: California Water Code Section 13752 blocks the public from inspecting the logs from any well-drilling companies. Much like the antiquated water rights which still rule the state, this 1951 law might be worth revisiting. Several efforts have attempted to end well log confidentiality but so far, these details remain out of the public eye.

Public data, public shaming

Before that 1997 ruling, the California Public Records Act allowed anyone to access utility information. It was, after all, from public utilities. The kind of details that were once made available can be seen in this story from the Los Angeles Times in 1991 (yep, there was a megadrought back then, too). As part of its Internal and External Water Audit Program, the city of San Diego used to publish a list of the city’s top 100 water users.

Helen Copley, the publisher of the Union-Tribune newspaper, made her own headlines for using 10,000 gallons per day on her 9.5-acre La Jolla estate:

“We are doing a very good job of water conservation here,” Copley said, noting that her June, 1990, water bill was 39% lower than her June, 1989, bill. Water conservation efforts of Copley’s 10 full-time gardeners include watering pool-side plants individually instead of spraying an entire area, punching deep holes in soil to allow water to soak in, and pouring unused drinking water on plants. She said she is considering leaving one portion of her property unwatered.

You can quickly see how these same public shaming tactics could just get into people’s hands in the current-day social media landscape, no data required. You can easily report a waster via a 311 app or post a photo on Twitter when you can see someone’s sprinklers overwatering from the street.

Why if we are in drought are the watering the median on Jefferson Blvd in Playa Vista? #waterhog #CAdrought #drought

— Joy Newcomb (@thirdiphoto) April 15, 2015

But it does seem like making this very specific information officially public can make a difference. The city of Montecito, for example, which made national headlines when it was uncovered that cut its water usage 48 per cent from the year before.

Information equals conservation

The type of data that impacts the largest majority of the state’s water consumers arrives from the local utility every month. My monthly bill tells me how many gallons of water I used last month and if it was more or less than the month prior. Depending on your utility company, you might also be able to see how your usage compares to others in your neighbourhood. Now a slew of new apps are trying to make that usage more transparent and top of mind for residents. The biggest issue here isn’t that information is necessarily being withheld, it’s just a painfully slow process for cities to release the datasets.

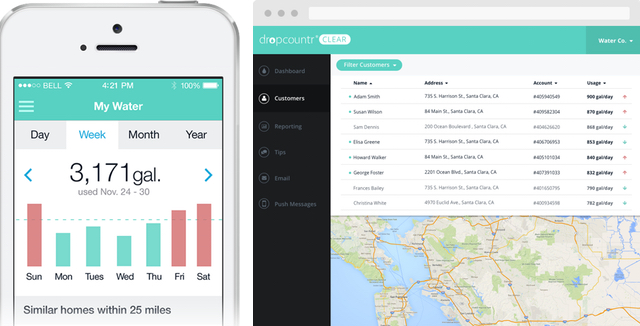

I tried to sign up for an app called Dropcountr which would help me track and manage my water consumption from my iPhone, but was dismayed to discover that LA’s Department of Water and Power hadn’t yet released enough data for me to use it. “In order to make our app actually work we have to partner with the utilities to get the information flowing,” says Robb Barnitt, Dropcountr’s founder. “We have huge user interest and they’re just as frustrated as we are.”

Dropcountr wants its users to be able to track their water use day-to-day; their CLEAR system allows utility companies to manage customers and send messages about conservation

To make it easier to sync city data with their app, Dropcountr has even developed a meter data management product called CLEAR to help utilities gather this very information and pass it along more efficiently to their customers. “Our argument is that a lot more people look at their phones than their bill and getting it front and center is key to conservation,” says Barnitt. He argues that if more California cities switched to a system like their app, they could not only reduce usage but also help send reminders about watering days or new rebates offered for low-flow showers, for example. But they need access to the data to make it work.

The battle for groundwater

Utility-regulated water consumption is only part of the data picture. The rest is actually hidden from view — it’s underground. Of far greater concern at the moment is groundwater use information, since the state’s aquifers are being depleted due to surface water scarcity. And if someone’s wasting or stealing water — including farms — it’s harder to see and report.

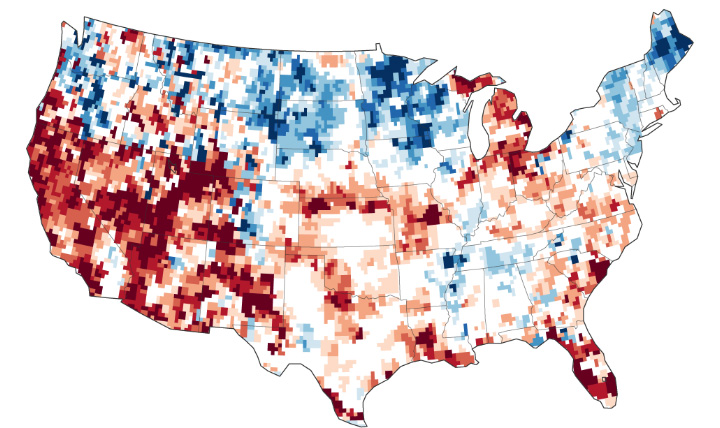

There is plenty of reporting available from scientists on groundwater levels. USGS, NOAA, and NASA, for example, have all been doing extensive groundwater surveys to study how quickly aquifers are being drained. What we know now is that the country is in trouble when it comes to groundwater, and it’s not just California. This information has even inspired hackathons where data scientists are looking at how more open government policies can inspire better agricultural methods.

In this July 2014 image, NASA’s Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) combines data with other satellites and ground-based measurements to model the relative amount of water stored in underground aquifers

The problem in California specifically is that we don’t know who is taking that water out. Up until last year, groundwater was not regulated by the state, and the laws which were passed last summer will take a few years to be fully in effect. Some communities are reporting record-high numbers of requests for new wells to be drilled — shouldn’t we be able to know who’s making them? How about larger agricultural interests that are siphoning off water from smaller farms? And wouldn’t it be important to know how much groundwater that, say, oil companies are extracting?

In the meantime, efforts to try to make this groundwater information public have been swatted down by courts, like a 2014 attempt by the First Amendment Coalition to get the information of businesses like golf courses in the Coachella Valley Water District, the infamously irrigated desert community east of LA.

It’s a privacy issue, the president of the water board told the Desert Sun:

“CVWD fought this lawsuit because we believe it is important to protect private customer data, whether that customer is a homeowner, a business or a private pumper,” board president John Powell Jr. said in a statement.

So we’re back to the same issue of open data being “protected,” while some customers are almost certainly silently sucking the state dry.

This data becomes even more important as municipalities are lining up to negotiate with the state about how much they actually need to reduce their water use in light of the statewide 25 per cent reduction mandated on April 1. Many cities argue that they have already been able to reduce their water use so much that they shouldn’t be subject to another 25 per cent, and they have got the records to prove it. Along with those records, the municipalities should be required to hand over all of that information to the public. You want to get water from the state? Show us all the data.