The pursuit of lock picking is as old as the lock, which is itself as old as civilisation. But in the entire history of the world, there was only one brief moment, lasting about 70 years, where you could put something under lock and key — a chest, a safe, your home — and have complete, unwavering certainty that no intruder could get to it.

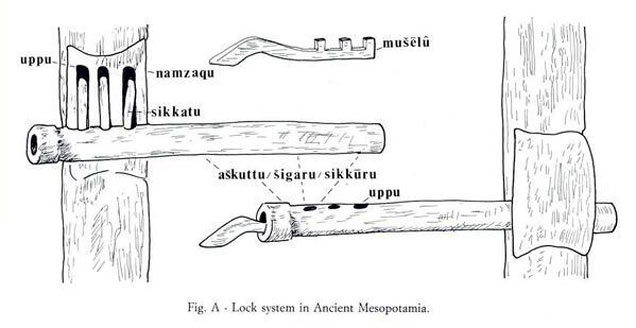

[An ancient Mesopotamian lock. Courtesy of Dan Potts]

This is a feeling that security experts call “perfect security.” Since we lost perfect security in the 1850s, it has has remained elusive. Despite tremendous leaps forward in security technology, we have never been able to get perfect security back. Locks go back at least as far as ancient Egypt (though perhaps originating in ancient Mesopotamia).

From the Middle Ages on for hundreds of years, locks were not very good. The best that locksmiths could do was add features like false keyholes that might at best might confuse a trespasser. But everything changed in 1770s with the arrival of an inventor named Joseph Bramah to the English locksmithing scene.

Joseph Bramah was a polymath engineer who would come to be known as one of the fathers of pneumatic power. But he also applied his talents towards improving locks. Bramah created a lock that was vastly superior to any the world ever seen. His so-called “Bramah safety lock” had layers of complexity in between the key and the deadbolt which Bramah believed made it 100 per cent theft-proof. Bramah was so confident in his design that he published a pamphlet detailing exactly how they worked.

[Joseph Bramah tells all in this this 1785 manifesto.]

Joseph Bramah had another idea that would revolutionise locksmithing — turning it into a contest. As soon as he had a padlock version of this lock that he felt confident in, he put it in the window of his London storefront, and painted on it a challenge:

[Joseph Bramah’s challenge lock: “The artist who can make an instrument that will pick or open this lock shall receive 200 Guineas the moment it is produced.” 200 Guineas in 1777 would be about £20,000 today.]

Many people tried to crack Bramah’s challenge lock, but no one, not even with their own tools, could get it open.

Bramah’s new unbeatable lock — and the hooplah surrounding it — caught the attention of the British crown. The British government wanted to up the game; they wanted a lock that wouldn’t just be unbreakable, but would also alert the owner if someone tried to open it. Another locksmith named Jeremiah Chubb met that challenge with his Chubb detector lock. The government awarded Chubb £100 for his innovation.

[Diagram of the Chubb Detector Lock]

The way Chubb’s lock worked was that if a lock picker tried to lift one of the tumblers up too high, a latching mechanism would trigger, causing the lock to seize up. When that happened, even the key wouldn’t open the lock. To reset the lock, the owner would have to put in a different key and rotate it in the opposite direction to reset the tumblers. Thus, if lock owners went to unlock a chest, or a vault, or a front door, and found that their key didn’t work, they would know that someone had tried to get in — and that they had failed.

As these newer and better locks were getting invented, the public spectacle around them rose to a fever-pitch. At one point they offered a convicted housebreaker parole if he could break the Chubb lock; eventually the prisoner turned the lock back in unbroken.

For years, the names Chubb and Bramah were all but interchangeable with “perfect security” — but only until the Lock Controversy of 1851.

[The Great Exhibition at Crystal Palace, 1851. Courtesy of The British Library.]

In 1851, London was hosting The Great Exhibition — the first international exhibition of manufactured products. One of the attendees was A C Hobbs, an American locksmith. Back in the States, Hobbs had made a name for himself by showing bank managers that their locks could be easily picked and convincing them to buy one of his. Hobbs was selling lots of locks this way.

On day one of the exhibition, Hobbs publicly announced that he would pick the Chubb detector lock — the one that stops working if you pick it incorrectly.

A witness wrote that it took Hobbs about 25 minutes. And the way Hobbs did it was to use the lock against itself. He would pick it until he tripped the detector mechanism, causing the lock to seize up. That would give Hobbs information about how it worked and then he would pick the lock in the opposite direction to reset the detector. He’d go back and forth firing and resetting the detector until the lock told him everything he needed to know about how to get it open.

But the Chubb detector lock was really just a warm up. The main event was the Bramah safety lock — the one with the challenge painted on it in gold lettering, which had been sitting Bramah’s storefront window for 70 years, unbeaten, taunting lock pickers everywhere.

A C Hobbs threw down the gauntlet.

[Diagram of the Bramah Safety Lock]

Josesph Bramah had died by this point, and his sons were running his shop. They gave Hobbs a room above the store where could stay for 30 days while he worked on the lock. He was allowed to set it up however he wanted and use all his own tools. Monitors came to check in on him periodically. After working on the lock for about 52 hours over the course of fourteen days, Hobbs opened the Bramah safety lock.

Overnight, the feeling of perfect security had evaporated. And we have never gotten it back.

[Credit: Andy Wright]

Locksmiths weren’t able to convince the public that perfect security could be restored, but they did keep inventing new locks. One such locksmith was Linus Yale, Jr. You have probably seen present-day locks with the name “Yale” on them — that’s because Yale’s company was able to mass produce their locks at a scale that no one had before. The design was called “pin and tumbler” — it became the world’s most common lock, and they are still made today. It’s probably the lock you have on your door.

The pin and tumbler lock is fairly easy to pick for someone who knows what they’re doing. But despite what movies would have you believe, it can’t usually be done with just a pick, or a paperclip, or a hairpin. There’s a second tool you’ll need: an L-shaped piece of metal called a tension wrench.

The tension wrench applies rotational tension to the lock while the pick works on the pins inside.

[A lock pick (left) and tension wrench. Credit: Dan Tentler]

The video below demonstrates how the inside of the lock works:

The lock on your front door is probably pretty easy to pick, but using a crowbar or going through a window would probably also suffice. It’s not just locks that keep us safe — it’s the existing social order. Today, locks have become a social construct as much as they are a mechanical construct.

The world may have moved away from Joseph Bramah’s “perfect security”, but his legacy of locksport lives on — even if the competition itself looks a bit like tedious factory work.

99% Invisible producer Sam Greenspan spoke with Leigh Honeywell, a digital security expert and amateur lock picking instructor; and Schuyler Towne, a security anthropologist with the Ronin Institute. Schuyler just published a paper positing that locksmithing began in Ancient Mesopotamia, and that the Egyptians got it from them.

This posthas been republished with permission from Roman Mars. It was originally published on 99% Invisible’s blog, which accompanies each podcast.