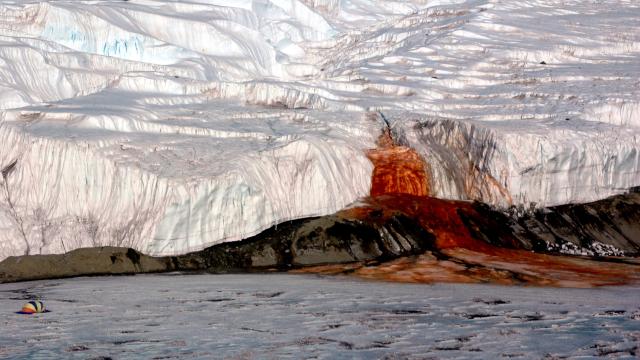

At Blood Falls, deep red iron-rich water oozes out of a glacier. It’s dramatic and unmissable on its own, but Blood Falls has always hinted at some greater hidden thing — that would be a vast subterranean network of briny waters, which scientists have just started to map.

The salty water are likely the remnants of an ancient sea that still host microbial life. In a study published in Nature Communications today, scientists flew an electronmagnetic sensor over Taylor Valley in Antarctica. Based on the sensor’s readings, they could tell whether it was ice, soil, or something else entirely — likely liquid brine. “These inferred brines are widespread within permafrost and extend below glaciers and lakes,” they write.

A helicopter flies the sensor over Lake Frxyell in the McMurdo Dry Valleys, Antarctica. Credit: L. Jansan

The flights were conducted over the Antarctic austral summer in 2011. More recently, microbiologist Jill Mikucki, who helped carry out this electromagnetic research, led a team to actually sample the subterranean liquid brine. You can read about that expedition below. Those results aren’t published yet, but we’ll be waiting for them eagerly.

Top image: Peter Rejcek, National Science Foundation

Against vast whiteness of Antarctica, Blood Falls bleeds a deep dramatic red. The colour comes from iron-rich ancient seawater trapped under the ice for 2 million years. For the first time, scientists have been able to take a sample from deep under the ice.

The five-story tall Blood Falls was first discovered in 1911. In 2004, a team including Jill Mikucki, a microbiologist now at the University of Tennessee Knoxville, sampled the microbial life at the mouth of the falls. Because the microbes oozing out normally live in dark, oxygen-less, and extremely salt places, Blood Falls is a unique place to study extremophiles outside of their inaccessible natural habitat.

Mikucki went on to publish her work in Science, but there was still a problem. Exposure to the light and oxygen at the mouth of the falls could skew the results. This winter (or summer in Antarctica), she returned with a team and the IceMole, which the Antarctic Sun describes:

The IceMole is a long rectangular metal box with a copper head and ice screw at one end capable of melting its way through ice — but not just straight down like a conventional electro-thermal drill. Differential heating at the tip allows IceMole to change directions. It looks a bit like a very large hypodermic needle poised to inoculate a glacier.

Using the IceMole, Mikucki’s team directly sampled a major vein that leads from the buried brine reservoir to the falls. (The reservoir itself is even further up the glacier and buried below even more ice, making it a considerable challenge.) To locate the liquid veins and guide the IceMole, the team used thermometers placed in boreholes in the ice.

The team will be analysing these new, uncontaminated samples for chemical content and microbial life. Blood Falls is pretty much unlike any other place on Earth, so the extremophiles that live in it, isolated for millions of years, are likely to be pretty unique, too. [Antarctica Sun]

Top image: Peter Rejcek, National Science Foundation