It took less than four hours for jurors to agree that Ross Ulbricht was the man behind the persona of Silk Road kingpin Dread Pirate Roberts, responsible for running an infamous online drug empire. It takes Deep Web, a new documentary about the Silk Road trial, less than two hours to poke apart the narrative prosecutors used to put Ulbricht behind bars.

Directed by Alex Winter (director of the Napster documentary Downloaded, though probably better-known for his role as William S. Preston, Esquire in the Bill & Ted films), Deep Web comes to a very different conclusion than the Federal Court of Manhattan.

Winter’s former co-star Keanu Reeves narrates most of the film, but it begins with a voiceover from crypto-anarchist Amir Taaki, who rails against fascism of state power and argues that the internet needs services (or, “a giant fuck you to the system”) that operate outside of state control.

The decision to begin the documentary with this anti-state bent reveals its perspective quickly: Winter wants to convince viewers that the Silk Road was as much a vital political statement as it was a narcotics-obtaining platform, and that Ulbricht did not get a fair trial for his association with it.

That Deep Web has an agenda is not necessarily a problem. The problem is the way it tries to fulfil that agenda. The tightly paced, provocative documentary raises two sharp points about the Silk Road trial, and one utterly naive one.

There are several enormously compelling arguments for why Ulbricht should not be in jail, and Deep Web shines when it hits on them — through interviews from former Silk Road vendors, Ulbricht’s family and childhood friends, defence lawyers, law enforcement, crypto-anarchists like Cody Wilson, and journalists.

One theory, first suggested by defence lawyer Robert Dratel, is that Ulbricht did create the Silk Road but was not solely responsible for much of the Dread Pirate Roberts’ activity, that multiple people collectively ran the site. Site administrator VarietyJones is pinned as another potential DPR; Winter interviews a Silk Road vendor who insists that more than one person ran the DPR account. This is a credible theory that the defence was not allowed to mount in court, and Deep Web argues persuasively that pinning the blame solely on Ulbricht was an act of convenience, not justice.

And then there’s the issue of the Silk Road server. As I’ve pointed out before, the question of how the government found and copied the Silk Road’s server went unanswered during Ulbricht’s trial, and Deep Web repeatedly questions the validity of that decision. There’s reason to suspect the FBI obtained the information illegally and that the evidence acquired through the server should be thrown out. Dratel recently filed for a retrial and cited the fact that the government conducted warrantless surveillance as his reasoning.

The film makes salient points about the Silk Road’s social and political value as a hotbed for cyberpunk dissidents and anti-authoritarian discourse. The vendors Winter interviews talk about how vibrant the community forums were, and how Silk Road had enormous potential to reduce harm by removing the need to get drugs on the street and enabling users to review drugs for quality. The FBI shutdown of the Silk Road is framed as something provoked by political motivations rather than any imminent danger posed by the service.

But Winter makes a decision that undercuts these points. The film’s biggest problem is that it paints Ulbricht as a sort of martyr and scapegoat and such an all-around good guy he couldn’t possibly be a criminal mastermind. The second half of Deep Web focuses on the efforts of Lyn Ulbricht, Ross’s mother, as she attempts to rally support for her son. The crux of Lyn’s argument is that Ross is straight-up too nice to be a drug kingpin.

She presents, as evidence, a rose that Ross fashioned out of toilet paper for her from prison. Winter seems to agree: He shows footage of Ross goofing around in a poofy skirt. He interviews Ross’s childhood friend, who recalls a story about Ulbricht emphatically saving the life of a bee — literally, a variation of the old “couldn’t hurt a fly” defence.

Deep Web’s focus on Ulbricht’s likability is misguided. The idea that Ulbricht is incapable of criminal activity because he’s a young, educated, polite, white hippie is laughable, and it damages an otherwise valid argument. Ulbricht should have a retrial. The Silk Road did have social merit both as a community and as a less violent method of drug distribution. Even if Ulbricht had been a volatile punk who spit in his mum’s face, that wouldn’t change how messed-up the trial was, or the basic philosophical tenets or potential social benefit of the Silk Road.

Those points are salient and the film teases them out in a way that both newcomers and people familiar with the case will understand. It also serves as an engaging explainer about the technology that allows illegal businesses to operate and the philosophical underpinnings of why they were created. Unfortunately, the emphasis on Ulbricht’s innocence by dint of his gentle nature dampens the film’s message and gives it the occasional whiff of a propaganda piece.

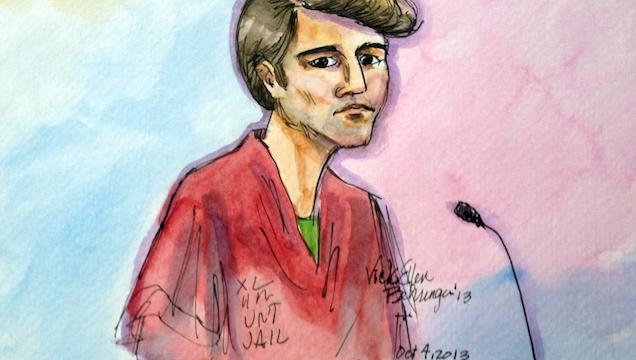

Picture: AP