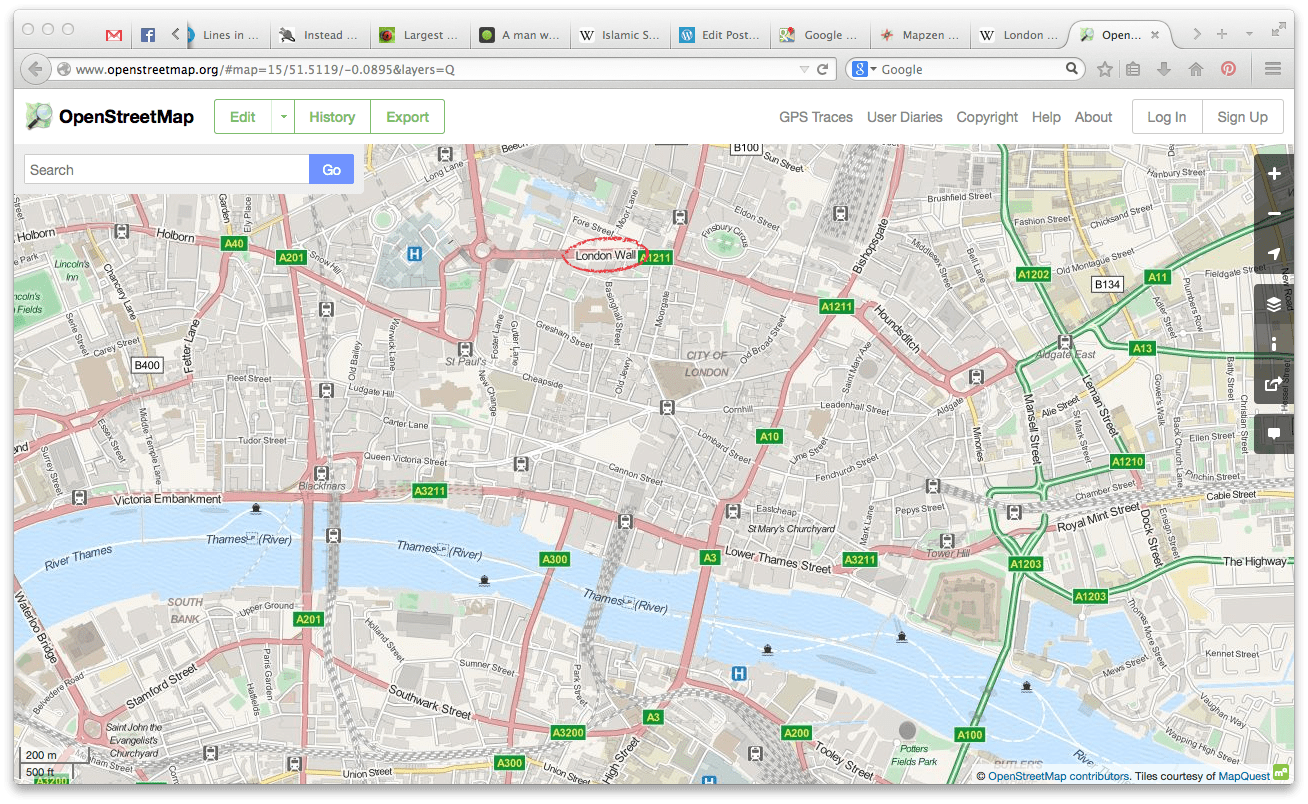

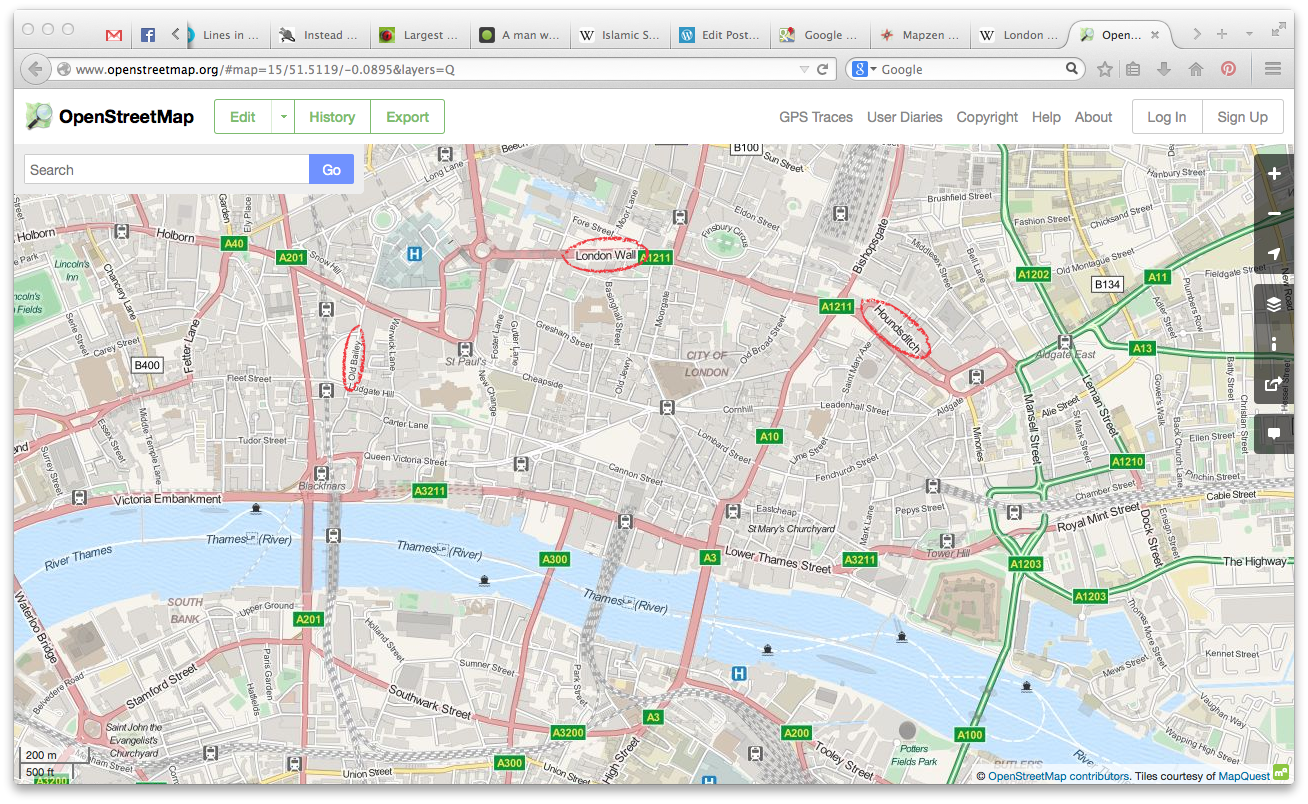

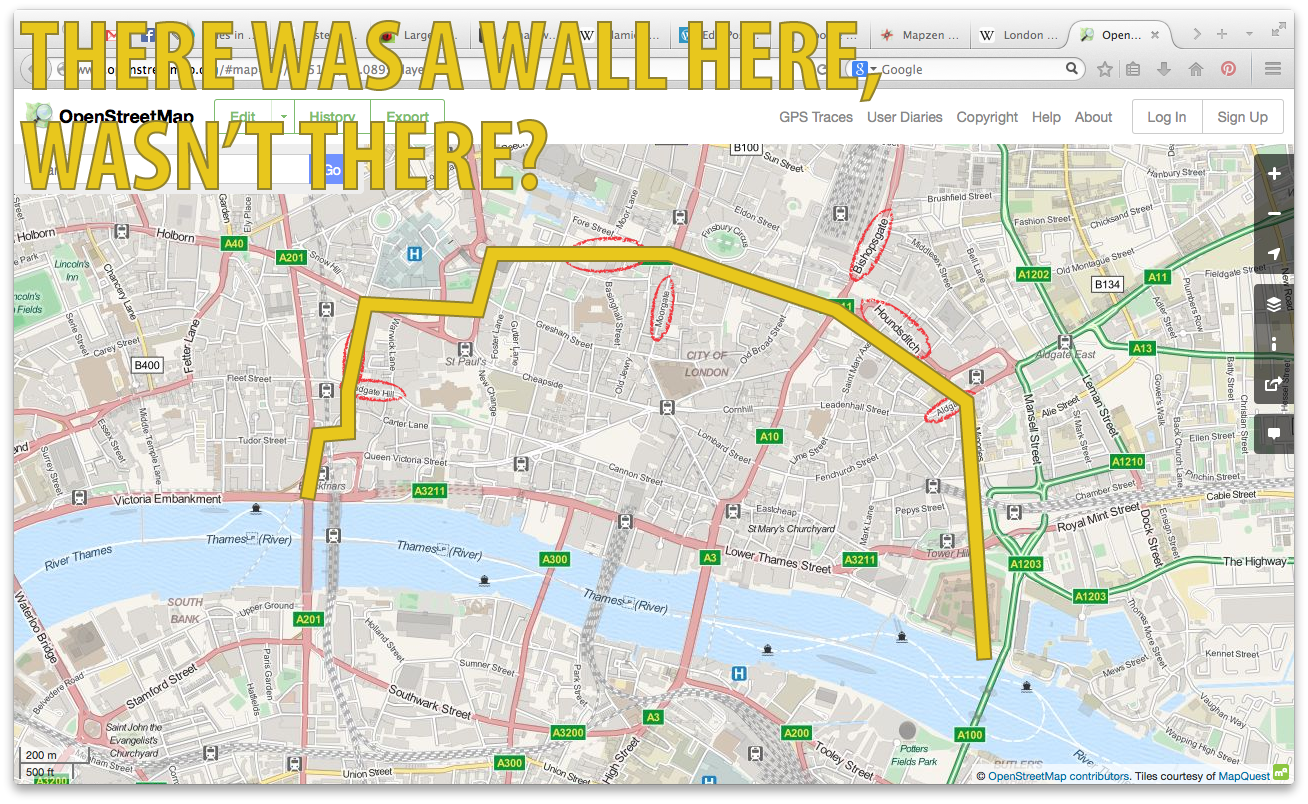

So in your spare time you’re looking at an aerial view of London on your favourite online mapping service (as one does), when you notice a street called London Wall.

And as you’re looking at your map, you notice other wall-y things, like Old Bailey and Houndsditch.

And then you notice that perpendicular to these wall-y things are lots of gate-y things: Ludgate Hill, Newgate, Moorgate, Bishopsgate, Aldgate.

And at about this point you start to see a shape and realise,

You can learn a lot about a city’s history by looking at a map of it. If you know what to look for, you can see how high places, walls, and other fortifications had a major effect in shaping our cities.

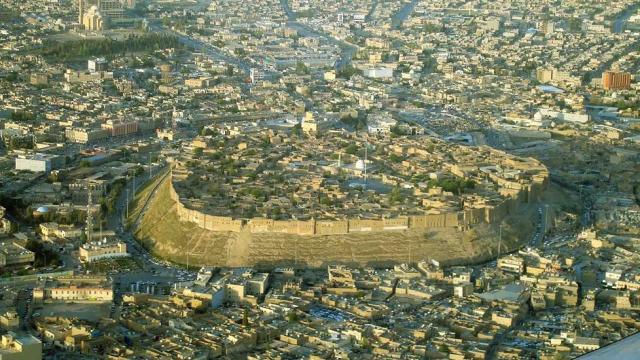

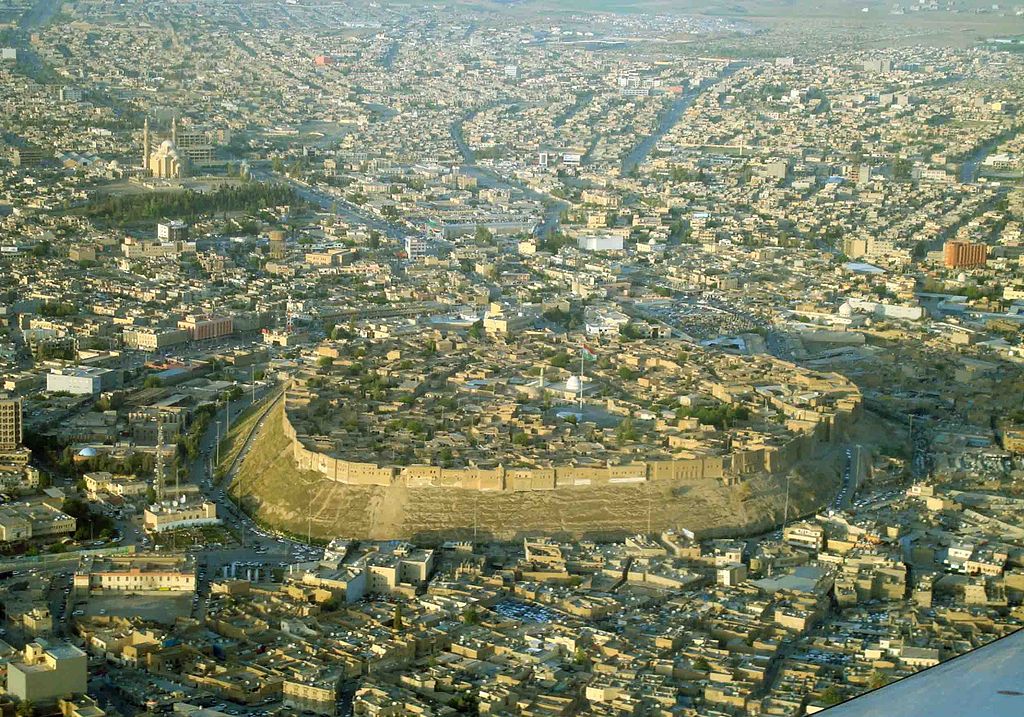

Early settlements all around the world were formed on the tops of hills. Hills are naturally defensible, because they allow you to see a greater distance and force your enemy to expend energy getting up the hill. Even in the large, flat expanses of the Levant, cities would create the advantages found on the more natural hill forts of Europe by building giant piles of dirt, or tells.

It wasn’t a stretch to get from “let’s build our city on this hill” to “this hill would be really great with a wall around it.” And thus, the citadel was born.

The citadel, of course, had different regional names, including the acropolis and the oppidum. Initially they were built of whatever was available, be it stone, wood, mud brick, or rammed earth. But in most places, stone or masonry eventually prevailed.

Groß Raden Archaeological Open Air Museum in Germany

In many cities, the fortified citadel grew to house only the city’s political and/or religious elite, while the normal residents were outside of the walls and subject to attack. But eventually the rulers decided that it was worthwhile to defend their soldiers, scholars and artisans, and cities began erecting full perimeter walls.

The weapons these walls were built to defend from were mostly just guys with swords, arrows, and in some cases fairly light siege equipment. As such, they didn’t need to be particularly thick, but they did need to be high. These walls often followed contours and were somewhat organic. They had fairly regularly spaced towers from which to shoot arrows or throw rocks, and were usually the joints at which straight walls would change direction.

The walls and towers of Rothenburg ob der Tauber, Germany

More importantly for urban design, the city wall provided a natural growth boundary. Especially during the uncertain times of the European Dark Ages and the invasions of the Germans, Huns, Slavs, Vikings, Arabs and Mongols (that’s everyone who invaded anything between the end of the Roman Empire and the introduction of the cannon, right? You get my point), there was a huge incentive to be inside the city walls rather than unprotected in the fields or the lawless countryside. The European feudal system only added fuel to the urban fire; peasants and slaves alike would flee to cities to escape their masters. In Germany, the law was that a serf was a free citizen of a city after a year and a day, thus the phrase Stadtluft macht frei nach Jahr und Tag (“city air makes you free after a year and a day”), better known for its shorthand, Stadtluft macht frei (“city air makes you free”).

The end of this phase of wall building came with the cannon. Unlike previous siege engines like the catapult and trebuchet, which threw objects over city walls to cause damage within, the cannon, with just a few direct hits, could pierce a wall, allowing for foot soldiers to enter the city. The vertical wall laid out perpendicular to the enemy allowed the cannon ball to focus all of its energy on one point, causing maximum destruction. The solution was to not try to necessarily stop the ball, but to diminish its destructive power by deflecting it. And thus the star-shaped wall was born.

These walls were not vertical and not perpendicular, but formed a jagged, pointed wall that sloped back toward the city. The angled and sloped walls, which were also much thicker, made it more likely that a cannon ball would simply bounce off and roll away harmlessly. The star points on the walls also allowed soldiers a forward position from which to attack the enemy, with the civilian population located further back from the action.

Star-shaped walls were massive feats of engineering, and only the wealthiest cities could fully enclose themselves within them. Some cities would create small forward military towns which would be heavily fortified, such as Palmanova outside of Venice. But in many cities would simply build a star-walled fort at a strategic location, such as the confluence of two rivers (Fort Pitt at Pittsburgh) or on the harbour (Fort McHenry at Baltimore).

Fort McHenry guarding Baltimore Harbour

There aren’t many cities whose star-shapped walls or forts remain. That is because they take up a huge amount of land, and as many cities, particularly in the west, began to feel less threatened by foreign armies, they wanted to use that land for other purposes. Many of these areas were redeveloped for public use. For instance, the former site of Fort Pitt in Pittsburgh is now Point State Park, where only traces of the former fort (as well as its French predecessor, Fort Duquesne) remain.

The outlines of Fort Duquesne (smaller, left) and Fort Pitt (larger, right) at Point State Park, Pittsburgh via Google Earth

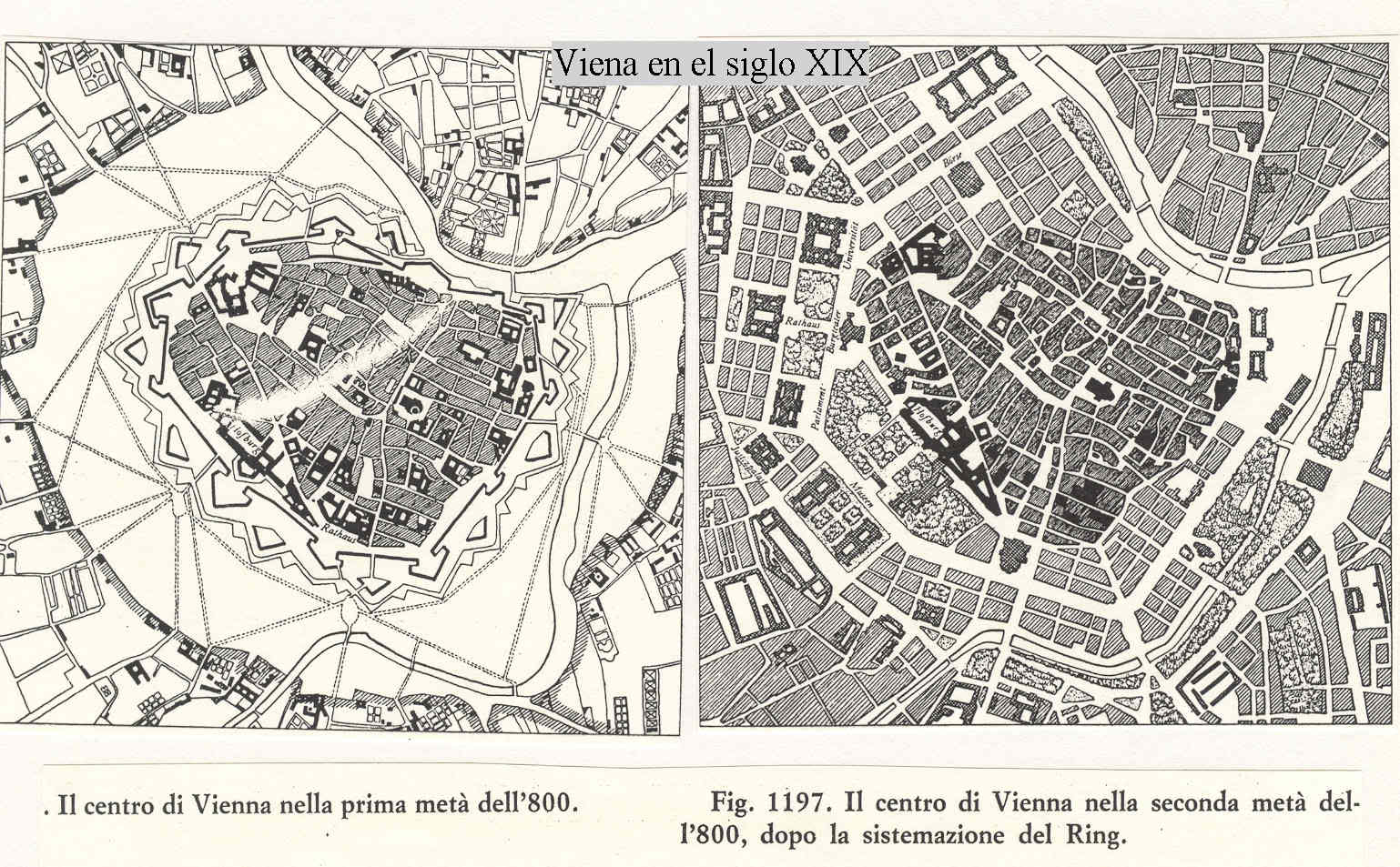

One famous example of a star-walled ring being replaced is the Ringstraße in Vienna. In the 1800s, Vienna had a star wall around its old quarter, but new districts had sprung up on the outside of the wall, and completely encircled it. Vienna was essentially the hole in a fortified doughnut. In the 1860s, the city chose to tear down its old fortifications, replacing them with a ring road, public parks, and major public buildings.

Ringstraße, before and after the redevelopment of the fortifications

It was about this time that explosive artillery shells were introduced, which star-shaped fortifications did not perform well against. These weapons also lead to the end of urban fortifications. The radius of damage from explosive shells was just too large for cities to feel comfortable going against, and the defence of cities fell to rings or lines of polygonal forts set back about eight miles from the city. Yet even without the enclosing walls, there was still an incentive to be in the city, where you were protected by the ring of forts, rather than in suburbs of the open countryside. That incentive came later, with the introduction of aerial bombardment and, later, nuclear weapons.

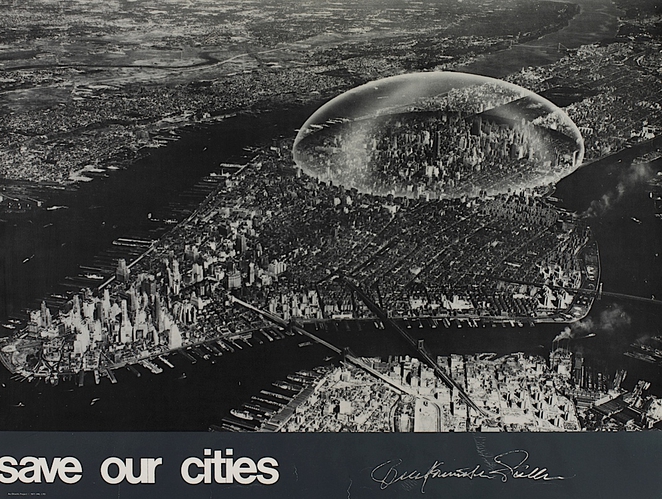

The nuclear era was the first time that the incentive for defence actually pushed people out of cities. When you have a single weapon that can kill hundreds of thousands in an instant and level an entire city, urban areas start to look less like refuges and more like targets. While there were many factors that led to suburbanization in America, the fear of a Soviet nuclear attack cannot be overlooked. One of the many reasons the interstate highway system was built was so that cities could be evacuated in case of an emergency, and one could imagine that those who fled for the suburbs were simply planning ahead.

That being said, there have been several proposals and even a few attempts at creating urban defenses in the nuclear age. There were many proposals for domed cities a la Buckminster Fuller, although his domes were largely meant as a means to prevent air pollution and provide city-wide climate control. The Underground City of Beijing, built during a spat with the Soviets in the 70s, was a network of underground tunnels, featuring shops, warehouses, and even mushroom farms (since mushrooms can grow without light), and supposedly could have held all of Beijing’s population of 6 million at the time. Switzerland, which is just chock full of air raid shelters, intended a double use for theSonnenberg Tunnel outside of Lucerne, which would have been able to house 20,000 people in the event of a nuclear attack.

I think part of the reason that my generation is returning to the city, although it may not be a conscious factor, is that the Cold War is over, and there really isn’t a world power out there with the air force and nuclear capabilities to attack us the way the Soviets could have. While it may have been a perfectly reasonable fear of nuclear annihilation that encouraged our parents or grandparents to leave cities, we don’t have that same fear. The greatest outside threat to our safety is no longer a State with official armed forces, but the small, loosely organised groups and individuals that today are the perpetrators of terrorism. But with few exceptions, terrorists cannot attack a large area at once, and although cities do employ counterterrorism measures, the targets of terrorism aren’t cities, they are usually individual properties or persons. That is why today we are seeing a resurgence of defensive construction, not on the city scale, but on the scale of the individual building.

Bollards, bollards everywhere at HHS in Washington, DC

While defence no longer encourages us to move to cities as it once did, it allows us to, more than it may have our parents or grandparents. The technology of war, as well as its general presence, may continue to be a factor in how we design our cities in the future, but the city of today is a safe place, and getting safer. As Stephen Pinker points out in The Better Angels of our Nature, violence in the world is on the decline, both on the scales of the individual and the nation state. With less to fear, we may be more able to enjoy the benefits that the city has to offer us.

This article has been reposted with permission from Munson’s City. To read in its entirety, head here. For more from Dave Munson, you can check out his blog here or follow him on Twitter here.

Dave is an urban planner and designer working in the Washington, DC area.