In 1995 Eugene Volokh wrote the most paleofuturish article ever written. By that I mean it’s an incredibly prescient meditation on the future of media and technology. But it has just enough weird anachronisms to remind us that nobody can predict the future with absolute certainty.

Think of it as the uncanny valley of old futurism — so incredibly close to the future that actually arrived, but just inaccurate enough that it gives you a weird feeling in the pit of your stomach. Something is just a bit… off.

Volokh’s paper was titled “Cheap Speech and What It Will Do” and was published in the Yale Law Review. The paper is worth reading in its entirety [pdf], but since it’s about 50 pages long (I think that’s like 800 pages when adjusted for internet inflation) I’ve pulled some quotes from the text and highlighted them below.

Essentially, Volokh makes the argument that high speed internet access (something he calls the infobahn) will completely reshape the media landscape. In the big picture, he was absolutely correct. Volokh predicts the rise of on-demand video streaming into people’s homes, the increased targeting of niche political media to specific audiences, and the electronic delivery of music. Of course, all these things came to pass.

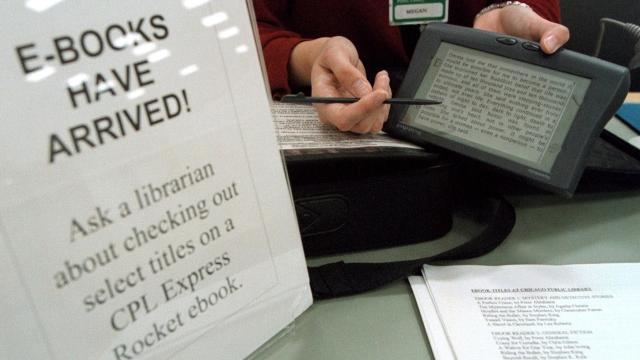

Where Volokh’s article shows its age is in both the terminology used and the predicted costs of new technologies for consuming media. For example, when it comes to the future of print media, Volokh assumes that everything comparable to newspaper and magazine-length articles will be printed out — as most people predicted at the time. Books, he concedes, might be read on e-readers (something he calls a cbook) but he couldn’t imagine a world where those readers are inexpensive:

The cbook itself may be a sizable upfront investment, however, and it may be particularly hard to afford for parents of small children, because the children may be likely to break it or lose it.

The true revolution in the various iterations of the e-reader over the past few years has been its affordability. The cheapest Amazon Kindle is now $US69, which doesn’t make it disposable, but it’s well within reach of middle class Americans. This is why 50 per cent of American households now have an e-reader or tablet. Cheap electronic books and the devices we read them on were hard to envision as recently as 20 years ago.

But Volokh’s predictions around the ability to distribute and update articles via this infobahn (eventually printed at home or otherwise) was certainly spot on:

[…] cbooks will allow timelier distribution of the material. A Newsweek could deliver news to people that’s genuinely current, rather than two or three days out of date. Newspapers could update their stories as news comes in, and would no longer have to be up to a day behind broadcasters. This will help the consumer as well as the publisher; and once some publishers do this, competitive pressures will push others to follow.

Just as Volokh had a hard time imagining words that weren’t printed out for consumption, he assumed that music would usually need to physically be recorded onto some medium like MiniDisc after being electronically delivered to the end user:

Once the music arrives-in data form-at your home, it will need to be recorded on some high-quality medium. Two familiar media are nonstarters: Normal analogue audiotape is too low-quality, and today’s CDs are read-only. But two recently introduced technologies — digital compact cassettes (DCCs) and MiniDiscs-might have what it takes. They both provide sound quality as good as that of a CD; you should be able to download music to them from your home computer, and then play it at home, in your car, or in your Walkman. Today this equipment costs a lot, but prices are expected to fall as the technology improves and economies of scale kick in, just as they did for normal CD equipment.

It’s amusing for those of us here in the second decade of the 21st century to read that recording on CD was a non-starter in 1995. But that was a reasonable perspective in the mid-90s. I vaguely recall a kid in my middle school in the late 90s who was one of the first to get a CD-burner for his home computer. He’d download songs for other kids from Napster and burn them to CD. Both the downloading and the burning took a long time and he charged a nice premium to make custom mix-CDs for other students.

Throughout the article Volokh does seem to underestimate the potential reach of the internet though, especially when it comes to where newspaper columnists will want to publish:

Note that, unlike record stores — which I think will be largely displaced by the electronic music databases — opinion columns in newspapers will survive. People will still buy newspapers for news and will expect to get their familiar columnists, too. Moreover, an up-and-coming columnist may still prefer to be published by a newspaper, with potential access to millions of readers, instead of trying to find his own following on the electronic services. My claim is only that electronic opinion columns will thrive alongside newspapers.

We’re certainly seeing this media star versus established media brand saga play out in new ventures like Ezra Klein’s Vox and Glenn Greenwald’s The Intercept.

Even calling it “Glenn Greenwald’s The Intercept” isn’t accurate, given that it’s run by former Gawker editor-in-chief John Cook, funded by eBay founder Pierre Omidyar, and has a decent sized staff. But there’s no doubting that Greenwald’s name is the one in big bright lights on the internet marquee. Becoming an enemy of the state while reporting will apparently do that.

The ability to customise your media exposure is arguably still very much in its infancy here in 2014, but in 1995 it was downright sci-fi. But Volokh accurately predicted the function, if not the form, of things like Twitter:

No one wants to read, say, the whole Los Angeles Times, with all its stories about news, sports, entertainment, food, travel, cars, and so on. No one reads the newspaper cover to cover. People read most parts of some sections and some parts of others, and throw out the rest.

What people want are newspapers and magazines with stories about the things that interest them (just as they want radio with the songs they like). They may want a newspaper that has, for example, the top twenty international stories of the day (with a special focus on news from Africa), the top five national stories, the top five science stories, the top ten law stories, news about football and about the Los Angeles Dodgers, and, say, ten random stories just for the unexpected surprise.

Volokh wisely points out that the barrier to entry for media like TV will remain difficult if it aims to have high production values. This struggle continues here in 2014:

The cost of producing high-quality, high-production-values entertainment — from $US500,000 to over $US1 million per hour — will slow down this diversification. So long as production costs remain high, each new program will still have to appeal to many people. 9 Still, it will probably need less of an audience than it does today, when producers face both high production costs and limited distribution channels. Moreover, some video programming-talk shows, talking heads shows such as the McLaughlin Group, stand-up comedy, and some kinds of sporting events-costs relatively little to produce. Production of these shows ought to mushroom.

Netflix and Hulu are now creating original quality content, but it’s still so early in the game that it remains to be seen whether their most coveted programming can be financially viable.

The entire flattening out of the media long-tail will lead to increased polarization. Volokh was far from the first to predict this, but unlike his predecessors, he didn’t seem to think this would be a terribly negative thing:

But as the sources of information and entertainment become less generic and more custom-tailored, people may lose some of this common ground. They may find themselves having fewer shared cultural referents, and less common knowledge about current events, even if they have more knowledge about the events that interest them most.93 People who read the Democratic Party’s organ and people who read the Libertarian Party’s organ might have a hard time even speaking the same language about the issues.

Again, those who want to share common ground with their peers may choose to continue listening to Top 40, or watch news shows that aim for a well-rounded, mainstream view of the world. But many people won’t do this. It’s hardly likely that American society will fall apart because of this, but it’s at least possible that more diversity of sources might mean less common ground and less social cohesion.

Volokh examines the issues of copyrighted works and the inevitable decline of classifieds ad revenue in newspapers. He also dissects everything from the digitization of old books to the considerations that will have to be made for libraries in order for them to legally lend out digital books.

But it’s perhaps his outlook on apartment rentals that gives a reader in 2014 pause about just how far we’ve actually come in 20 short years:

A database of, say, all apartments for rent in the city would be much easier to search through than a newspaper classified section: From a public access terminal, the renter could ask for an instant list of all the one bedroom apartments renting for less than $US850 per month within three miles of UCLA, perhaps plus apartments that are a bit cheaper but a bit further, or more expensive but closer. The list should be more complete, because the information will be easier and cheaper to post. And the list should be timelier-the information will become available as soon as the landlord posts it, and can be removed as soon as the apartment is rented. Electronic classifieds are better on all counts than paper ones, and newspapers will have to adjust to a huge revenue loss when the paper classifieds stop coming in. The loss of classified revenues, coupled with the cost savings and opportunities for extra profits from electronic distribution, should help push newspaper publishers into going electronic.

Again, there’s some anachronistic language in there like “public access terminal” that reminds us this was written back in 1995. But he’s pretty accurately describing how people find apartments today.

His predictions about targeted advertising were also amazingly accurate:

[…] individualization of the media will let advertisers target customers better than ever before. Instead of one newspaper with ads aimed at several hundred thousand people, each electronically delivered newspaper will have ads calculated to fit the particular subscriber’s profile-age, sex, and whatever other information the newspaper gets at subscription time, or can deduce from the mix of stories he’s ordered. The same would be true for the other media. The greater ease of targeting ads may also change the way political campaigns reach voters.

Volokh raises a number of potential problems around the regulation of speech after the introduction of the infobahn, but in the end he comes out rather optimistic about the future of our connected world.

In my view, none of these changes, significant as they may be, should cause us to reconsider the basics of First Amendment law. The dangers of extremists with access to the media, of falsehoods with an audience in the millions, and of an ill-informed electorate are quite real; but the dangers of content regulation, it seems to me, are greater. And the dangers of regulation are exacerbated by the difficulty of doing anything about the most significant problems (here, the possibility that people will choose to watch or read infotainment instead of the important news of the day seems particularly intractable). Finally, the criticisms by Dean Thomas G. Krattenmaker and Professor L.A. Powe of the FCC’s attempts at content regulation seem to me hard to answer.

Still, the media will change, and change dramatically. As people find themselves in a new media environment there’ll be new calls for regulation, and new calls for changes to First Amendment doctrines that some people may think are no longer apt.

I may be wrong in my predictions about what the new media order will look like. But the one thing that seems certain is that the new order will, in many ways, be vastly different from the old.

There’s so much more to discuss in Volokh’s piece, including a much deeper dive into the free speech implications of this new media. But thanks to the “cheap speech” the internet provides, we’re going to leave it here and let you hash it out in the comments.

How accurate do you think Volokh’s paper was about the world we live in today?

Picture: Librarian Megan McArdle displays some text 3 August 2000 from a book available on one of nine new Rocket ebooks available at the Chicago Public Library, Getty