In 1812, the English novelist Frances Burney described her mounting terror as she prepared to undergo a mastectomy without any anaesthetic. Having two hours to wait until the dreaded event (her ‘execution’, as she put it), she wandered into the room where the operation was going to take place and ‘recoiled’. In an effort to control her fear she ‘walked backwards & forwards till I quieted all emotion, & became, by degrees, nearly stupid — torpid, without sentiment or consciousness’.

When seven men arrived, all dressed in black, and began laying down two ‘old mattresses’, covering them with an ‘old sheet’, Burney ‘began to tremble violently, more with distaste & horrour of the preparations even than of the pain’. When told to mount the bed, she stood ‘suspended, for a moment, [contemplating] whether I should not abruptly escape — I looked at the door, the windows — I felt desperate’.

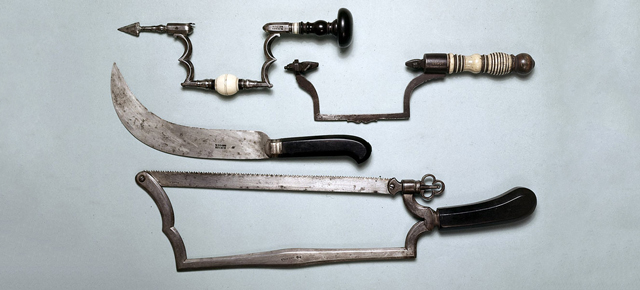

Submission, however, was necessary. The surgeon spread a cambric handkerchief over her face and took up the knife. Burney was consumed by a ‘terror that surpasses all description’. When ‘the dreadful steel was plunged into the breast — cutting through veins — arteries — flesh — nerves’, she wrote: ‘I needed no injunctions not to restrain my cries. I began a scream that lasted unintermittingly during the whole time of the incident — & I almost marvel that it rings not in my Ears still! so excruciating was the agony.’

A century later, physicians took a very different view of pain narratives. Writing in the 1860s, Peter Mere Latham (physician extraordinary to Queen Victoria) inverted Mandeville’s comment, grumbling that ‘every person’s complaint is interesting to himself, he is apt to discourse about it rather too much at large, and too little to edification’. Latham lamented that ‘among the upper classes of life, we are obliged to listen to the patients’ tale’ — presumably because their social status entitled them to opine — but he confessed that ‘we generally cut [their accounts of pain] as short as possible, in order to get to our plan of investigation’.

With the invention of chloroform in the 1840s, doctors celebrated the fact that the ‘groans and shrieks of sufferers beneath the surgeons’ knives and saws, were all hushed’. So said the surgeon-dentist Walter Blundell. According to Blundell, writing in 1854, surgeons were now able to carry out their work ‘as on breathless, lifeless forms’. Anaesthetics rendered patients passive, unconscious bodies, stripped of sensibility, agency and, critically, words.

The emotional and aesthetic ‘thinning’ of clinical languages has continued ever since, moving the subjective experience of pain further towards the periphery of medical discourse. Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (or fMRI) promises to eradicate the subjective person-in-pain altogether: she is not required to speak, nor even to point. Pain is little more than ‘an altered brain state’. The complex pain narratives of earlier periods have been decisively dismissed.

Patients themselves are no less eloquent about their pain, despite this new secular approach to it. To take some examples from the medical, legal and academic literature of the past few decades, one paraplegic explained that he felt as if ‘a family of snakes’ was ‘squirming’ in his buttocks. Another patient described pain as ‘like a demand from Her Majesty’s Inspector of Taxes’. A woman who experienced phantom limb pain after her arm was amputated observed that it felt like ‘champagne bubbles and blisters’. A man with chronic back pain said; ‘my back hurt so bad I felt like I had a large grapefruit down about the curve of the back’. Even more creative was the woman who said her headache felt ‘like a bowl of Screaming Yellow Zonkers popping hard behind my forehead’.

In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, these communities of fellow-sufferers have been bolstered by the internet. Feeling belittled or ignored by their physicians (who, to be fair, face immense pressure to ‘process’ patients ‘efficiently’), people-in-pain have turned to social media and online communities. These sites offer sufferers a language with which to frame their pain; they enable them to communicate this pain to others; and they provide sufferers with a community in which they feel that their experiences are validated. ‘Bodying forth’ (a term coined by the Swiss psychotherapist Medard Boss in the 1970s) into cyberspace enables pained bodies to fling themselves out of the constraints of geography, medical power regimes and social stigmatisation.

Aeon is a new digital magazine of ideas and culture, publishing an original essay every weekday. It sets out to invigorate conversations about worldviews, commissioning fine writers in a range of genres, including memoir, science and social reportage.