It’s the year 2051. Welcome to a view of the American landscape. Urban areas have swollen with people. Range and pasturelands have shrunk. There’s a bit more forest than there was back in 2014, a result of economic incentives driving more timber production. These are a few of the predictions of a new study on how people will use privately held U.S. lands in coming decades.

Economists and ecologists from several universities and the World Wildlife Fund put their expertise together to come up with an econometric model, which looked at how market forces surrounding the cost of agricultural goods are likely to shape land-use across the country.

The research, published May 5 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, was designed to help scientists and policymakers better understand the drivers of land-use change and how policies can alter use.

“Providing food, timber, energy, housing, and other goods and services, while maintaining ecosystem functions and biodiversity that underpin their sustainable supply, is one of the great challenges of our time,” the authors write.

The power of economics to alter the landscape

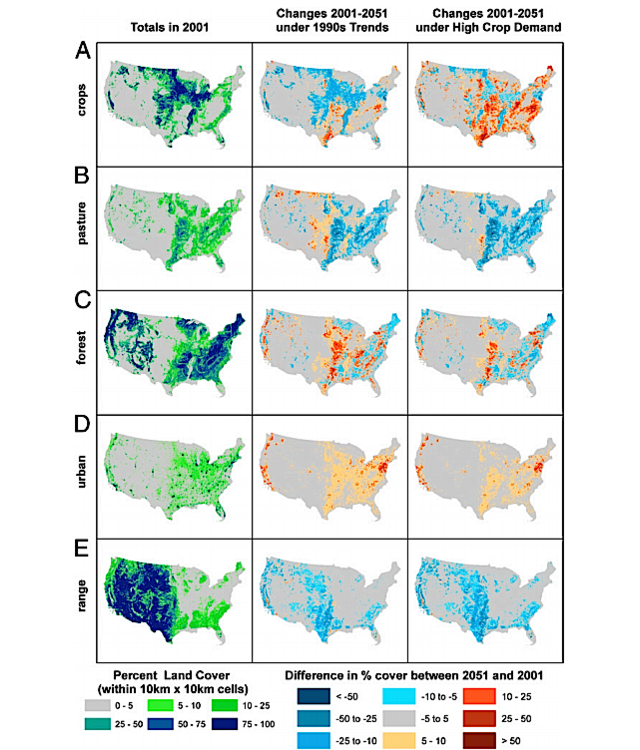

They ran the model from 2001 to 2051 assuming two baseline scenarios — the first mirroring low agricultural prices seen through the 1990s that drove land use away from crop production and into forested and urban lands that offered higher returns on investment. The second scenario assumes a 10 per cent increase in crop prices every five years, a condition like that which dominated from 2007 to 2012 and drove expansion of agricultural land.

Under the high-crop-price scenario, the study found that cropland coverage in the contiguous United States would increase by almost 109,000 square miles. This land increase would amount to double the calories of food produced. With lower agricultural commodity prices, the country would see a shrinking of croplands by more than 43,000 square miles. Increases in crop yields from improved agricultural processes and technology advances would mean 50 per cent more calories produced on less land compared to 2001.

More cropland being planted under the high-agricultural-price scenario would also trigger a decrease of almost 118,000 square miles of pasturelands and 120,000 square miles of range. The lower crop-price scenario, on the other hand, would mean bigger gains for forests of almost 63,000 square miles and 114,000 square miles of urban land over gains that would be seen with high crop demand.

Image: Spatial patterns in land cover in 2001 and changes between 2001 and 2051 under two baseline scenarios, 1990s trends and high crop demand, for crops (A), pasture (B), forest (C), urban (D), and range (E). Courtesy Lawler et al./PNAS.

In both scenarios, wildlife is likely to be the loser. The team studied 194 amphibians, influential species, game species, and at-risk birds. They reported that around a quarter of species they studied would lose more than 10 per cent of their habitat. Only 19 per cent of species would gain as much habitat in the lower crop-price scenario while less than 5 per cent of studied species would gain as much under the higher crop-price scenario.

The researchers introduced non-market mechanisms to see if they could help control some of the change, which would impact ecosystem functioning and lower the land’s ability to provide valuable resources and services if allowed to proceed unchecked. By paying people $US100 an acre per year to convert land into forest and taxing them $US100 an acre for removing forest, the model showed a 14 per cent increase in forested land over the baseline.

“The most interesting outcome of the study to me is that the market is going to drive major land-use changes and policies will have a limited ability to control it,” says researcher Joshua Lawler, a University of Washington assistant professor of landscape ecology. “These market pressures are likely to be so strong that they will make it hard to constrain changes based on policies like taxes and incentive payments.”

Lawler tells Txchnologist that the study didn’t look at the full toolbox of carrots and sticks available to maximise goals like habitat conservation and sustainable exploitation of resources. “To have a larger impact, these incentives and taxes would have to be more aggressive, but they will still likely be limited by market feedbacks,” he says.

But, he says, a number of instruments could do more to improve the outlook for forests and range. Stricter regulations, zoning laws, and enrolling sensitive lands in conservation easement programs all could help guide land use. Also technological advances that increase farming and tree-harvesting intensity on agricultural lands could take off some of the pressure.

Indeed, the authors conclude, “Policy interventions need to be aggressive to significantly alter underlying land-use change trends and shift the trajectory of ecosystem service provision.”

Lawler continues: “By quantifying the landscape, our research showed that, without a policy of specifically growing natural lands, we saw a decrease in natural lands. In general, that translates to a decrease in ecosystem function and value.”

But he says there are other ways to get a handle on unfettered alteration of the landscape, as well. By improving landscape management practices, the impact of agricultural, commercial and residential land-use changes could be at least partially mitigated. “By reducing habitat fragmentation, avoiding clear-cutting of trees, using pesticides less intensively and reducing monoculturing of crops, you can reduce the impact,” he says. “These can improve ecosystem functions on the impacted land itself or on the lands surrounding them.”

This post originally appeared on Txchnologist.

Txchnologist is a digital magazine presented by GE that explores the wider world of science, technology and innovation.

Michael Keller is Managing Editor of Txchnologist. His science, technology, and international reporting work has appeared online and in newspapers, magazines and books, including the graphic novel Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species.

Lead image: MaxyM/Shutterstock