At the University of Oxford, a team of scholars led by the philosopher Rebecca Roache has begun thinking about the ways futuristic technologies might transform punishment. In January, I spoke with Roache and her colleagues Anders Sandberg and Hannah Maslen about emotional enhancement, ‘supercrimes’ and the ethics of eternal damnation. What follows is a condensed and edited transcript of our conversation.

This article is an excerpt of the original Q&A, which can be found on Aeon here.

What about life expansion that meddles with a person’s perception of time? Take someone convicted of a heinous crime, like the torture and murder of a child. Would it be unethical to tinker with the brain so that this person experiences a 1,000-year jail sentence in his or her mind?

Roache: There are a number of psychoactive drugs that distort people’s sense of time, so you could imagine developing a pill or a liquid that made someone feel like they were serving a 1,000-year sentence. Of course, there is a widely held view that any amount of tinkering with a person’s brain is unacceptably invasive. But you might not need to interfere with the brain directly. There is a long history of using the prison environment itself to affect prisoners’ subjective experience. During the Spanish Civil War [in the 1930s] there was actually a prison where modern art was used to make the environment aesthetically unpleasant. Also, prison cells themselves have been designed to make them more claustrophobic, and some prison beds are specifically made to be uncomfortable.

I haven’t found any specific cases of time dilation being used in prisons, but time distortion is a technique that is sometimes used in interrogation, where people are exposed to constant light, or unusual light fluctuations, so that they can’t tell what time of day it is. But in that case it’s not being used as a punishment, per se, it’s being used to break people’s sense of reality so that they become more dependent on the interrogator, and more pliable as a result. In that sense, a time-slowing pill would be a pretty radical innovation in the history of penal technology.

I wanted to close by moving beyond imprisonment, to ask you about the future of punishment more broadly. Are there any alternative punishments that technology might enable, and that you can see on the horizon now? What surprising things might we see down the line?

Roache: We have been thinking a lot about surveillance and punishment lately. Already, we see governments using ankle bracelets to track people in various ways, and many of them are fairly elaborate. For instance, some of these devices allow you to commute to work, but they also give you a curfew and keep a close eye on your location. You can imagine this being refined further, so that your ankle bracelet bans you from entering establishments that sell alcohol. This could be used to punish people who happen to like going to pubs, or it could be used to reform severe alcoholics. Either way, technologies of this sort seem to be edging up to a level of behaviour control that makes some people uneasy, due to questions about personal autonomy.

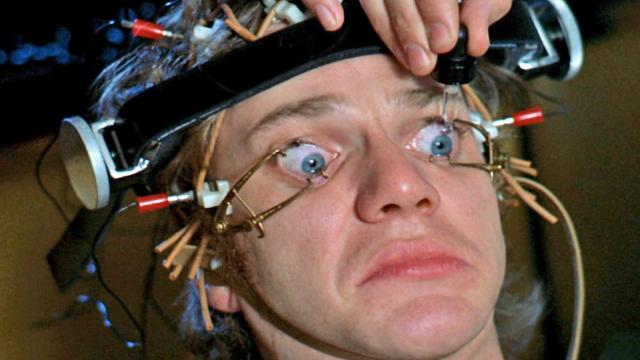

It’s one thing to lose your personal liberty as a result of being confined in a prison, but you are still allowed to believe whatever you want while you are in there. In the UK, for instance, you cannot withhold religious manuscripts from a prisoner unless you have a very good reason. These concerns about autonomy become particularly potent when you start talking about brain implants that could potentially control behaviour directly. The classic example is Robert G Heath [a psychiatrist at Tulane University in New Orleans], who did this famously creepy experiment [in the 1950s] using electrodes in the brain in an attempt to modify behaviour in people who were prone to violent psychosis. The electrodes were ostensibly being used to treat the patients, but he was also, rather gleefully, trying to move them in a socially approved direction. You can really see that in his infamous [1972] paper on ‘curing’ homosexuals. I think most Western societies would say ‘no thanks’ to that k ind of punishment.

To me, these questions about technology are interesting because they force us to rethink the truisms we currently hold about punishment. When we ask ourselves whether it’s inhumane to inflict a certain technology on someone, we have to make sure it’s not just the unfamiliarity that spooks us. And more importantly, we have to ask ourselves whether punishments like imprisonment are only considered humane because they are familiar, because we’ve all grown up in a world where imprisonment is what happens to people who commit crimes. Is it really OK to lock someone up for the best part of the only life they will ever have, or might it be more humane to tinker with their brains and set them free? When we ask that question, the goal isn’t simply to imagine a bunch of futuristic punishments — the goal is to look at today’s punishments through the lens of the future.

This article has been excerpted with permission from Aeon Magazine. To read in its entirety, head here.

Aeon is a new digital magazine of ideas and culture, publishing an original essay every weekday. It sets out to invigorate conversations about worldviews, commissioning fine writers in a range of genres, including memoir, science and social reportage.