For a brief period in the American saga, the astronaut was the man of the moment. No profession commanded as much awe and admiration. Widely regarded as the personification of all that was best in the country, the first astronauts were blanketed with the adulation usually accorded star quarterbacks, war heroes, and charismatic movie stars. Yet this was never part of NASA’s agenda.

In fact, there were concerted early efforts to avoid such celebrity. However, the men chosen to be the first Americans in space were raised in a culture that revered the stoic aviator, and many saw themselves as the latest members of that select spiritual brotherhood.

Celebrated in headlines, fiction, and film, the leather-jacketed pilot personified a new aristocracy during the first half of the twentieth century: a young adventurer whose courage and daring bridged continents and cultures. Prior to World War I, fledgling aviators and their early aeroplanes were frequently depicted on the covers of mass-circulation magazines and on advertising posters throughout Europe. Shortly after hostilities commenced in 1914, nationalistic publications enthralled the public with stirring tales about the most decorated pilots and their bravery in the skies, feats far removed from the mechanised horror in the trenches below. During the interwar years, adventure magazines and cinema screens often featured romantic depictions of the solitary fighter pilot, silk scarf flowing in the wind, engaging his fellow knights of the air in aerial combat in the skies over France, while overhead across America, former military pilots risked their lives by supporting themselves as barnstormers and flying the first airmail routes.

Into this post-war culture arose aviation’s first superstar, Charles A. Lindbergh, the story of whose solo transatlantic journey was known to every schoolboy in America during the decades that followed. The media attention that transformed Lindbergh from a unknown pilot from the Midwest into the most famous living person on the planet set the model — and offered a cautionary warning — for the American press’s treatment of the astronauts a quarter-century later.

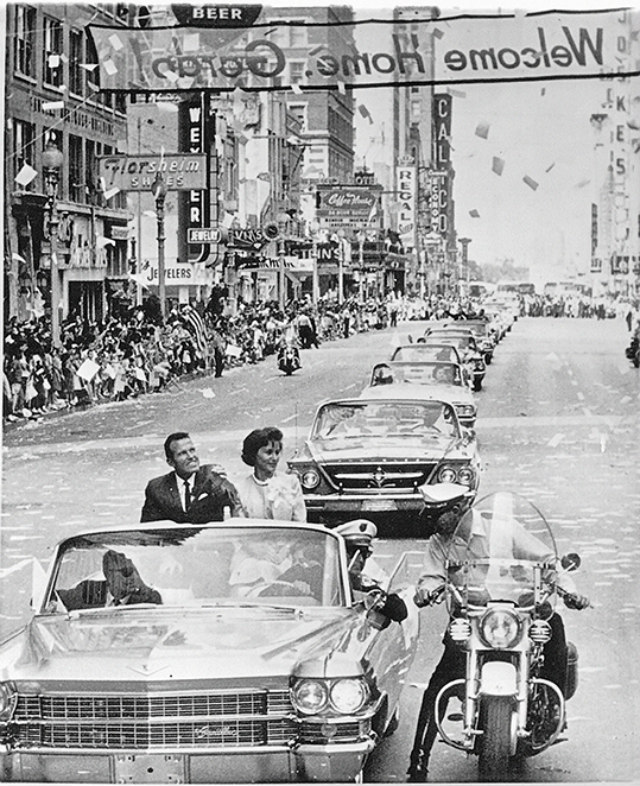

The initial group of seven astronauts got a sudden glimpse of their new public role on April 9, 1959, when they were first introduced to the world press in a crowded room in the Dolley Madison House in Washington D.C. The moment when the Mercury Seven first faced a barrage of clicking cameras and fielded unexpected questions from the Washington press corps is memorably recaptured in a key scene in Tom Wolfe’s The Right Stuff. The press’s insatiable curiosity reflected the country’s fascination and hunger for heroes and, in John Glenn, many journalists wondered if NASA had found the Lindbergh of the space age.

“NASA wasn’t out to market or create heroes,” recalled Gemini and Apollo veteran Gene Cernan, who was introduced to the public as member of the third group of astronauts in 1963. “The hero status was created by the nature of what we did, and by the public’s response to what we were doing.” Yet, as Apollo 7 astronaut Walt Cunningham wrote a few years after his mission, “In the glory years of manned space flight, what the country kept forgetting was that we were people. The only thing we did not see ourselves as was heroes . . . that was something the public craved, and the media had created — not that we didn’t enjoy the myth, we just never fully understood it.”

Initially portrayed as both warriors in the fight to dominate outer space and modern-day exemplars of the idealised traits of the American pioneering spirit, the first astronauts quickly realised that their public images were largely a creation thrust upon them by an adoring press. This public portrait was further honed and developed as a result of the exclusive Life magazine profiles orchestrated — and, indeed, moulded — by NASA’s Public Affairs Office. At the same time, NASA tried to avoid making any one astronaut overshadow his comrades. There was a concerted effort to define them as members of a unified team of pilots and technicians. Indeed, Leo Braudy in his essential history of celebrity, suggests that NASA’s insistence on a heroic team of astronauts and technicians was directly informed by knowledge of the disastrous political fortunes of Lindbergh, who in his highly public role as a private citizen urged accommodation with Hitler’s Germany on the eve of World War II.

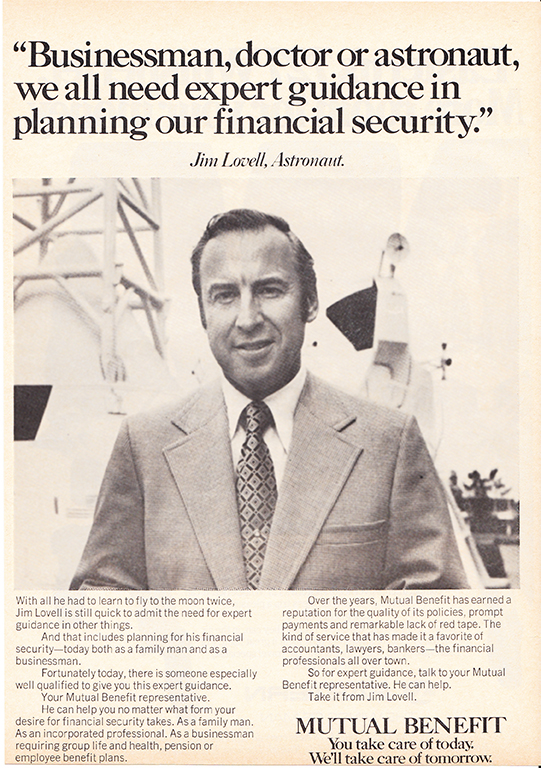

As the space race progressed, and NASA executed a number of “space firsts” during the Gemini program, the names of the second and third group of astronauts became nearly as well known. As perplexing as it was for the astronauts, especially the newer members of the team, it was part of the job — an occupational hazard that would follow them the rest of their lives. “No one could have predicted the public fascination with astronauts from the first unveiling of the Mercury Seven in 1959, through project Apollo,” wrote Roger D. Launius, a NASA Historian and Smithsonian Air and Space Museum Senior Curator for Human Spaceflight. “The astronauts as a celebrity and what that has meant in American life never dawned on anyone before. To the surprise and ultimate consternation of some NASA leaders, they immediately became national heroes and leading symbols of the fledgling space program.”

Wearing the mantle of instant celebrities — even if they hadn’t yet flown in space — the astronauts were often confronted by situations in which well-wishers desired an autograph or a photo or a handshake. Mindful of their place as official representatives of NASA and the American space program, they invariably tried to accommodate

the public. “You had to give them a little something — you had to try,” said Cernan. “You couldn’t turn your back and walk off. Everything depended on how you related to people.” But sometimes the effort resulted in long lines and huge crowds, which easily destroyed the best of organised schedules of the Public Affairs Office. As the highest-profile figures in a space program being sold to the public, the astronauts could not afford to be seen in a negative light or get a reputation for rudeness. Therefore, the Public Affairs officer assigned to an astronaut was often required to play interference. He could put a limit on the available time an astronaut had to stand and mingle, informing the crowd that he had only five, ten, or fifteen minutes left — and thereby giving the hero a graceful exit. “They could hustle you in and out sometimes,” Cernan recalled. “Sometimes you’d get people starting to form a line for autographs — even before you had flown a mission — like a rookie baseball card kind of thing. And so, the Public Affairs Office guy would hustle you through.”

During the early years of the manned space program, Shorty Powers and NASA’s Public Affairs Office carefully crafted the images of the first Mercury astronauts, primarily through the Life/World Book contract. But by the time the Gemini program was underway during the mid-1960s, a change had occurred. The military control over immediate information and the astronauts’ personal stories during the Mercury era disappeared with Powers’s departure in 1963. Even though the Life/World Book contracts were still active, the increased influence of Julian Scheer and Paul Haney signaled a marked difference in Public Affairs management, and with it fewer restrictions on information given to the media. During Mercury and some early Gemini missions, mission audio transcripts were commonly edited and cleansed for language and clarity. In contrast, Apollo was provided to the world unedited and unpolished. As Cernan described it, “We didn’t doctor up the movie, didn’t edit anything out. What was said, was said.”

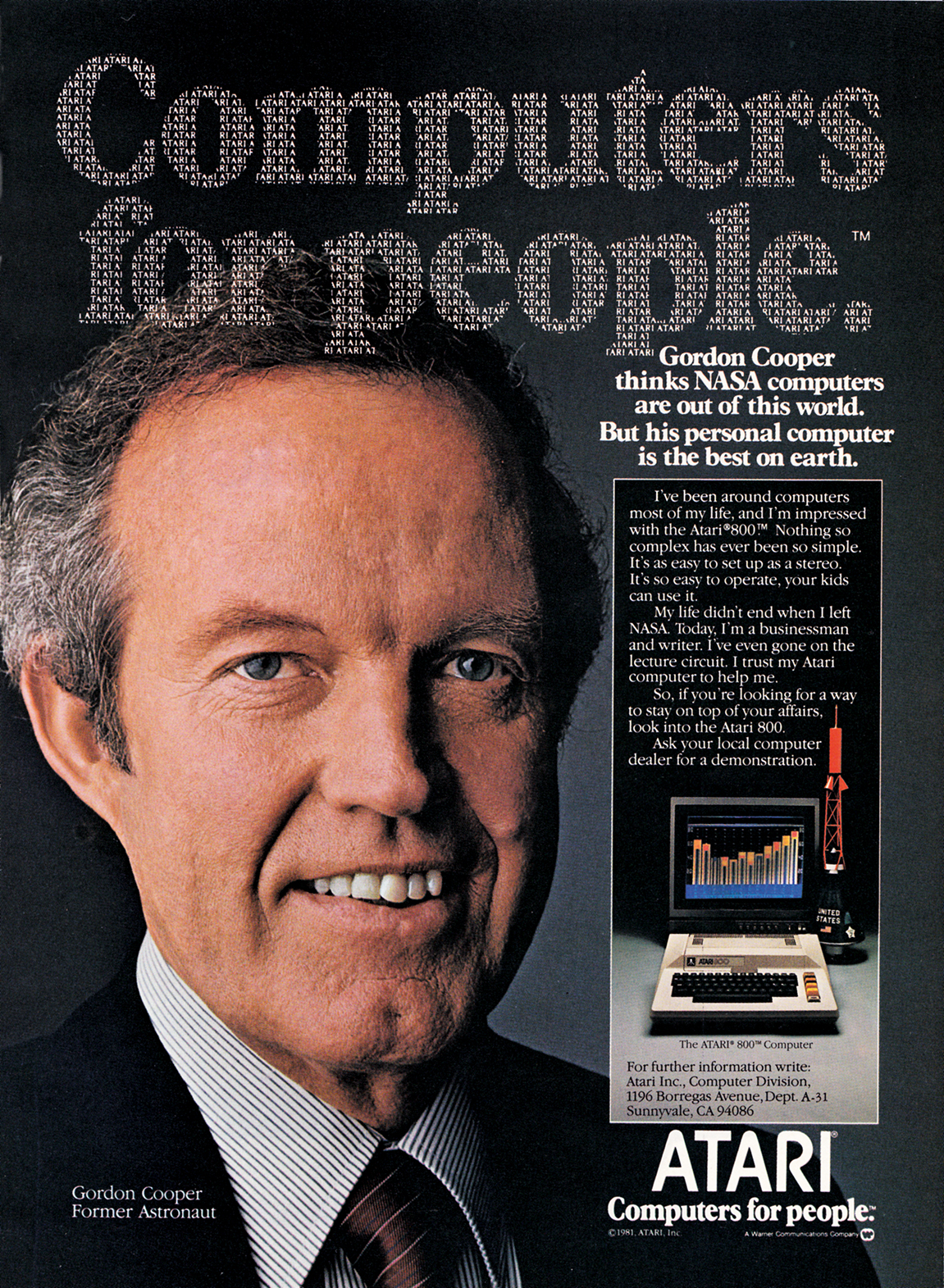

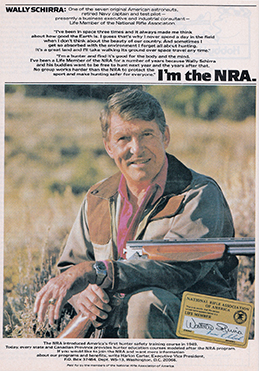

The instantaneous and uncensored release of information to the press placed severe limitations on anyone attempting to carefully craft a public image. And for the astronauts working under stressful conditions, in a new spacecraft and in situations that were both unscripted and often prone to unforeseen challenges, the Apollo program revealed how greatly things had changed as early as the first manned mission. During the Apollo 7 flight in October 1968, the world heard the cranky and cantankerous voice of veteran astronaut Wally Schirra commanding his last mission. He battled not only a head cold and a flight plan he thought was littered with too many extra experiments and frivolous activities, but he also battled openly with his colleagues down at Mission Control. The result was damage, not only to his image but also to his crew in the eyes of the media and NASA’s management. “The heavy workload at the outset of the mission, combined with his discomfort, made Wally more irascible by the day,” wrote Cunningham in his 1977 memoir. “He didn’t miss an opportunity to nail Mission Control to the wall. Donn and I were amazed at the patience of those in the control center with some of the outbursts that came their way. On the ground, they were well aware that every word of the air-to-ground communications was being fed directly to the press center, a fact of which we had not been informed. So Wally’s bad temper was making big news back home.” By piercing the veil on the earlier image of the astronaut as calm, cool, fun-loving adventurer, Schirra made the mistake of reminding everyone that he wasn’t superhuman.

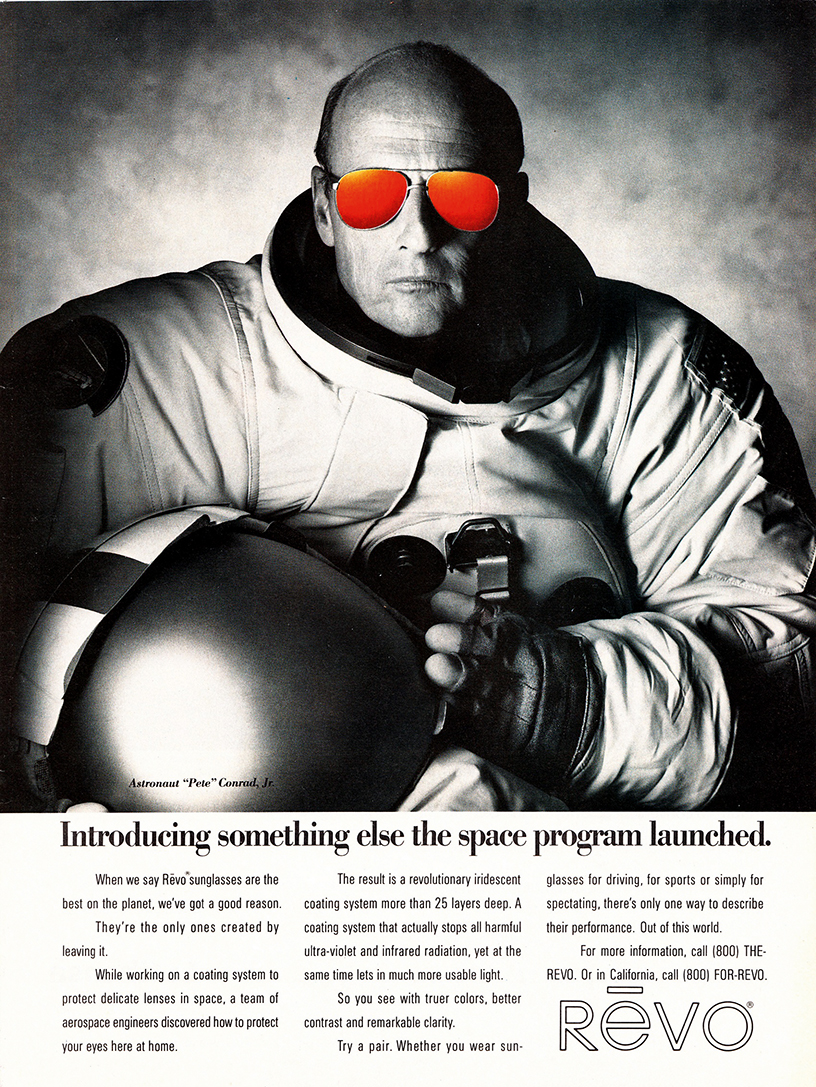

Even when the astronauts were not performing their job before the eyes and ears of world’s media, they were still in the limelight. “As astronauts, we were usually the biggest dudes in the crowd,” wrote Cunningham. “And frequently the only ones who couldn’t really pay their own way.” There were constant invitations wherever they traveled from businessmen, politicians, entertainers, and ordinary citizens — to attend parties, open houses, black-tie affairs, and the like. While the astronauts could not possibly accept all the invitations, they certainly accepted a good number of them. “In a convoluted way, NASA encouraged our socializing. We were mixing with the community and selling the program.” But the invitations usually had a catch — a favour, or the opportunity to use the astronaut’s celebrity to the benefit of the evening’s benefactor. Sometimes it wasn’t overt, but often it was, especially in the epicenters of Houston and the Cape. “There was the time we and the Schirras were attending a concert at the Houston Music Theatre — on passes,” Cunningham recalled. “We were introduced just before the show started and as we sat down, Wally smiled and whispered, ‘We just paid for our tickets.’”

In retrospect, it may seem amazing that access to the astronauts — among the biggest celebrities of the ’60s and early ’70s — reflected a bifurcated world: there was unfettered access down at the Cape or in Houston at social events, on the street or in a bar, while, at the same time, NASA Public Affairs and the Astronaut Office allowed only extremely limited access for official interview requests, especially in conjunction with a mission. “Access to the astronauts before a mission was extremely restricted due to their preparations,” veteran NASA Public Affairs officer Doug Ward recalled. “At that time, media interactions were usually during press conferences at the Manned Spacecraft Center and the Cape. Only a very select few might get a one-on-one interview.”

Veteran reporters were cognisant of the intense hours of training and preparation demanded of the astronauts in the weeks leading up to a mission, and they wouldn’t even bother requesting an interview. But for the hundreds — sometimes thousands — of reporters on a first trip to cover a mission, there was often bitter disappointment. Ward remembers that the Public Affairs Office would always have to turn them down. “These guys would get a stricken look and say, ‘Well I sold this to my editor on the assumption that I was going to get an astronaut interview.’” It just wasn’t possible. But that didn’t stop some of the reporters. “I remember, before Apollo 11 we had a guy come in from South America. He was just desperate and when he found out he couldn’t get access to the astronauts, he staked out their homes. We got a report from the local sheriff that he’d been turned in. He climbed up a tree adjacent to one of the astronaut’s houses and was trying to take pictures through the window. And John McLeish from our office had to speak to the sheriff and get the guy out of jail. Although there were rare occasions like that, the regulars who covered this thing as a full-time responsibility didn’t make those kinds of mistakes.”

Bill Larson, of ABC Radio and a veteran of local Florida reporting, described that period in his career as a lifestyle. “Back then you could walk into one of the restaurants or bars or whatever, and the chances were you would run into one or two of the astronauts. You could sit and talk, have a beer. And it was that kind of a feeling amongst the people here; the astronauts were like members of the family.” Gene Cernan agreed. “I had a lot of good friends in the press. We invited them into our house under the condition that, once they’re in our house, we have a beer or a scotch and soda, you leave the business outside.”

Naturally, that also made it difficult for journalists close to the astronauts to report on the personal side of their lives — the Life/World Book contract aside. “We got away with things that other people wouldn’t get away with, whether it was speeding or going places we couldn’t otherwise afford,” Cunningham recalled. “One thing after another came our way and we didn’t take the high road necessarily. We took advantage of a lot of those things. You couldn’t go anyplace without all the women in the place looking at you like, all of a sudden, you were Superman. It was an unreal kind of existence because, during those days, we were the celebrities’ celebrity.”

The reporters who covered the astronauts weren’t blind to what was going on. Like their counterparts in Washington, D.C., they chose not to report it. There was an understanding among the establishment press of that time to respect the boundaries between personal lives and professional lives. “Of course I knew about some very shaky marriages, some womanizing, some drinking, and I never reported it,” recalled Dora Jane Hamblin, one of the Life magazine reporters. “The guys wouldn’t have let me, and neither would NASA. It was common knowledge that several marriages hung together only because the men were afraid NASA would disapprove of divorce and take them off flights.”

While Life wouldn’t report these stories, it didn’t mean that more sensational outlets wouldn’t. The rumour mill was active and rampant. The astronauts, as celebrities, were exposed to all the temptations of modern day celebrity: groupies, hangers-on, wild parties, and handshake business propositions. Celebrity gossip magazines, such as Confidential, sent reporters to the Cape looking for stories, and some rumours couldn’t escape the ears of the local Florida and Houston gossip columnists. But the mainstream press tended to avoid these stories. They were committed to covering the big story and remained as focused on the goal of reaching the Moon as NASA and the astronauts.

During the ’60s and early ’70s, astro-gossip remained on the fringe. “Nearly all [of the media coverage] had us squarely on the side of God, country, and family,” wrote Buzz Aldrin in 1973. “To read those accounts was to believe we were the most simon-pure guys there had ever been. This simply was not so. We all went to church when we could, but we also celebrated some pretty wild nights.” In his memoir covering the same era, Walt Cunningham added, “What wasn’t realised at the time was the particular pedestal on which the media had placed us. In the years ahead they would contribute to protecting our reputations in a manner usually reserved only for national political figures.”

“In those early days, the PR people and the news people were very close and worked together,” added Larson. “Everybody was so closely knit on one desire: to get to the Moon. It was an amazing feeling. I’ve never been anywhere before or since with that sense of camaraderie and a belief in that you were involved in the greatest exploration in the history of mankind. It was a cooperative effort on everybody’s part.”Mark Bloom, veteran reporter for the New York Daily News and Reuters, concurred. “It was a great adventure story. We wanted them to make it. I wanted them to make it. We were very happy that they made it. But they weren’t perfect. We let a lot of the warts go by — I did. I let a lot of the warts go by.”

Conspicuously, one figure whose personal life generated little attention in the press was Neil Armstrong. Even when he divorced his wife of thirty-eight years, in 1994, the press barely noticed. Sometimes erroneously described as a recluse during the years after his retirement from NASA, Armstrong was not averse to making public statements and occasionally appearing at benefits supporting causes he championed. He even appeared in Chrysler television advertisements in 1979.

Armstrong and NASA management were keenly aware of what had befallen Charles Lindbergh in the years after his 1927 flight — the tragic kidnapping and death of his son, and the aviator’s controversial statements on the eve of World War II — and it has been widely reported that Lindbergh’s history influenced Armstrong’s decision to maintain a low public profile. In fact, Armstrong and Lindbergh, two shy Midwesterners with much in common in addition to their sudden fame, struck up a friendship shortly after the return of Apollo 11 and became active pen pals.

Equally aware of Lindbergh’s biography were the American journalists who had covered Armstrong’s years at NASA. Their decision to respect the privacy of “The First Man,” was continued by their successors during the last four decades of Armstrong’s life. The small number of news items published about Armstrong’s last forty years was both a reflection of Lindbergh’s shadow on the history of celebrity and a lasting testament to the unique bond that formed between the press and the astronauts during the Apollo era.

Marketing the Moon: The Selling of the Apollo Lunar Program is available on Amazon starting March 27, 2014.