They came from the best museums and universities in the country: Art historians, curators, artists and architects who probably never dreamed of joining the army. This band of unlikely soldiers was tasked with the uniquely challenging job of finding — and saving — Europe’s great masterpieces before the Nazis could steal or destroy them. They were called “Monument Men”.

That was their unofficial name, of course; it’s also the title of the George Clooney film loosely based on their story that opens in theatres today. Officially, their department was known as the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives program, created in 1943, after the director of the Museum of Modern Art — then still just a fledgling museum! — took his concerns about the destruction of European art to the White House. That June, FDR established the American Commission for the Protection and Salvage of Artistic and Historic Monuments in War Areas, which in turn created the MFAA.

War, of course, is the natural enemy of great cities and art; these are things that require care and stewardship, and in Europe of 1943, both were in short supply. By sending more than 400 soldiers and civilians to reduce the damage being caused by World War II, the US was doing something pretty much unprecedented: Fighting a shadow war, behind the scenes, that attempted to salvage the wreckage created along the front lines.

Top: the rescuing of Michelangelo’s Madonna and Child in Altaussee, Austria, in 1945. Bottom: this 1945 handout photo provided by the Smithsonian Institution shows the evacuating of artwork from Neuschwanstein Castle in Bavaria. AP Photo/Smithsonian Institution.

So, what was life like as a member of the MFAA? Usually, a few monument men were stationed in groups with troops along the front lines. That made it possible for them to help officers make battle decisions based on a clearer picture of what potential monuments and works of art stood in the way, and also to help identify and protect artworks and objects recovered from the Nazis.

Top: 16th November 1940: A man stands in the ruins of Coventry Cathedral after a German nighttime air-raid destroyed the centre of the city. Photo by George W. Hales/Fox Photos/Getty Images. Bottom: Even in London, great works were being destroyed: This 6th January 1940 photo shows a 400 year old painting and silver drinking vessels rescued from a jammed safe in St Lawrence Jewry. Photo by Keystone/Getty Images.

Sometimes, as the troops moved into a newly-won area, the MFAA would assess the damage and then make whatever repairs they could — including organising locals to carry out long-term work. An average day could mean anything from trudging dozens of miles between small towns, to covering ruined buildings and monuments with tarp, to lugging sculptures, paintings, or smashed architectural details from half-destroyed buildings to safety.

Top: Monuments Man George Stout moves the central panel of the Ghent Altarpiece in Altaussee, Austria in July of 1945. AP Photo/National Archives and Records Administration. Bottom: Monuments Man George Stout, second from right, with others as they remove Michelangelo’s Bruges Madonna from the salt mine in Altaussee, Austria, July 10, 1945. AP Photo/National Archives and Records Administration.

Though today, the monument men carry a certain air of mystery — after all, George Clooney is playing one in a movie! — they weren’t particularly well-loved by their fellow GIs. According to Ilaria Dagnini Brey, the author of The Venus Fixers: The Remarkable Story of the Allied Soldiers Who Saved Italy’s Art During World War II, members of the MFAA were often much older than normal soldiers — sometimes in their 40s and 50s.

In a wonderful article in Smithsonian Magazine about a band of MFAA men in Italy, Brey says that the age difference gained them a backhanded nickname: “Aged Military Gentlemen on Tour.”

The rescuing of art from Buxheim Monastery, Bavaria. AP Photo/Edward E. Adams, Smithsonian Institution.

The divide was also cultural, since MFAA men had unique backgrounds that would’ve seemed rarefied to the average 20-year-old soldier. Many were curators at the best museums in America, others were artists themselves or professors of art history at schools like Princeton, Yale, and Harvard.

They were uniquely ill-suited for the trials of war, but perfectly suited to the unique task at hand. Protecting monuments and great works of art as Allied troops moved through Europe was only half of the job, though. As the war raged, so did rumours of the looting being carried out by the Nazis, who were, in fact, stockpiling munitions along with priceless paintings and artifacts in salt mines across central Europe at the time.

Soldiers preparing a Rubens painting for shipment, 1945. Image: Archives of American Art.

In an amazing recollection, Captain Walker K. Hancock — a specialist with the MFAA — remembers discovering one secret room, walled up behind bricks inside one salt mine:

Crawling though the opening into the hidden room, I was at once forcibly struck with the realisation that this was no ordinary depository of works of art. The place had the aspect of a shrine.

Two hundred and 70-one artworks, many of them 18th-century court portraits and paintings apparently from the Sans Souci palace at Potsdam, lay scattered about. here were also several works of Lukas Cranach the Elder from a 1937 Berlin exhibition, and works by noted artists Boucher, Watteau and Chardin. On the right of the central passageway were three wooden coins, with the identifications indicating they contained the Hindenburgs and Frederick William I. In the last compartment on the left was the great metal casket of Frederick the Great.

Panicked, the Nazis had moved the caskets to the mine from their resting place beneath a nearby monument.

Hancock’s story was far from rare. The Third Reich had collected thousands of works over just a few years, ferreting them away in hideouts and mines. This was the “greatest treasure hunt in history,” a race against time before priceless works looted from museums, private homes, and often, Jewish collectors, could be sold off to private buyers.

At Neuschwanstein Castle, the fairytale castle that held one of the largest repositories, the monument men found 6,000 works looted from their Jewish owners. By 1945, the MFAA had set up base stations all over Germany to deal with the sheer volume of looted works — cataloging, storing, and determining the provenance of each piece.

Four men standing in the throne room of Neuschwanstein Castle in Bavaria, circa 1945. Image: Archives of American Art.

Still, many of these works were never recovered. Today, the Monuments Men Foundation (founded by Robert Edsel, the author of The Monuments Men) even maintains a public database of “Most Wanted Works” that are still missing, including pieces from Botticelli, Rodin, Monet, Cezanne, Mondrian and Caravaggio.

In fact, in November of last year, a $1.38 billion stash of art looted by the Nazis — much of it by Jewish artists — was discovered in an apartment in Munich. A month later, an art historian discovered two pieces of art inside the German parliament that had been stolen by the Nazis during the war.

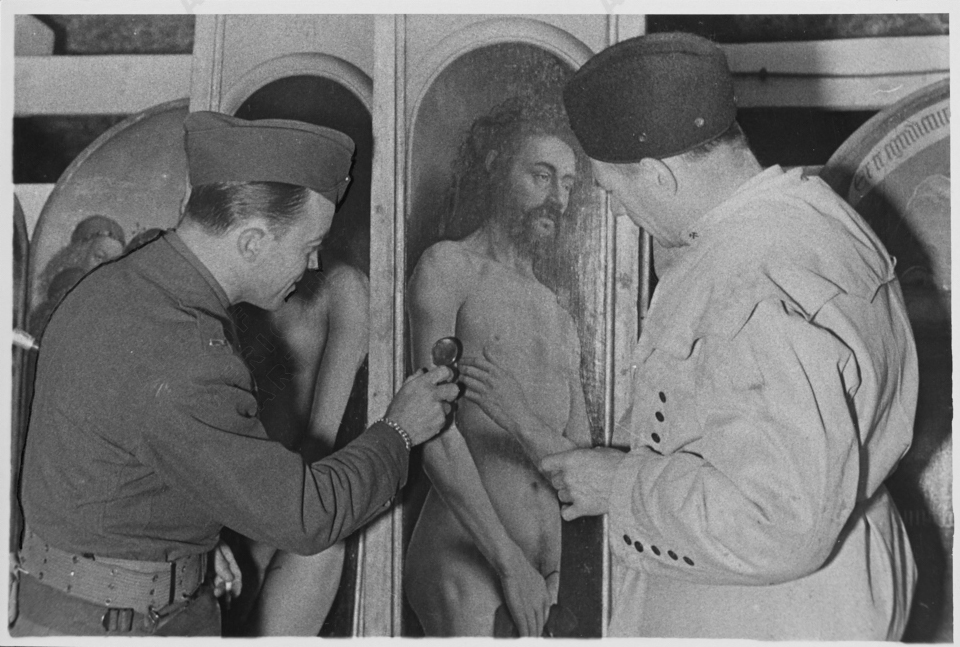

Lt. Kern & Karl Sieber examining the “Lamb,” the famous Ghent Altarpiece by Jan van Eyck, one of the, if not the greatest single art treasure of Belgium. Image: Archives of American Art.

In the spring of 1946, after all the MFAA members had returned home, their group was officially dissolved. From there on out, the State Department would handle its activities. In retrospect, it’s a shame.The MFAA was a unique institution: Bonded by the fact that they were people who had devoted their civilian lives to studying art, they were, in essence, a group of art lovers dropped into the middle of war zone — and in some ways, that was why they were so successful.

In some ways, it’s a tragedy that the Monuments Men story ended that year. The wars that would bring American troops onto foreign soil over the next 70 years would destroy countless priceless works of art and architecture in Iraq, Afghanistan, and even Eastern Europe and Vietnam. It’s hard not to wonder what a modern-day band of monument men and women could’ve saved.

For more on the monuments men, check out Robert Edsel’s book, The Monuments Men: Allied Heroes, Nazi Thieves and the Greatest Treasure Hunt in History, or Ilaria Dagnini Brey’s The Venus Fixers: The Remarkable Story of the Allied Soldiers Who Saved Italy’s Art During World War II. Or, you know, see the movie version tonight.

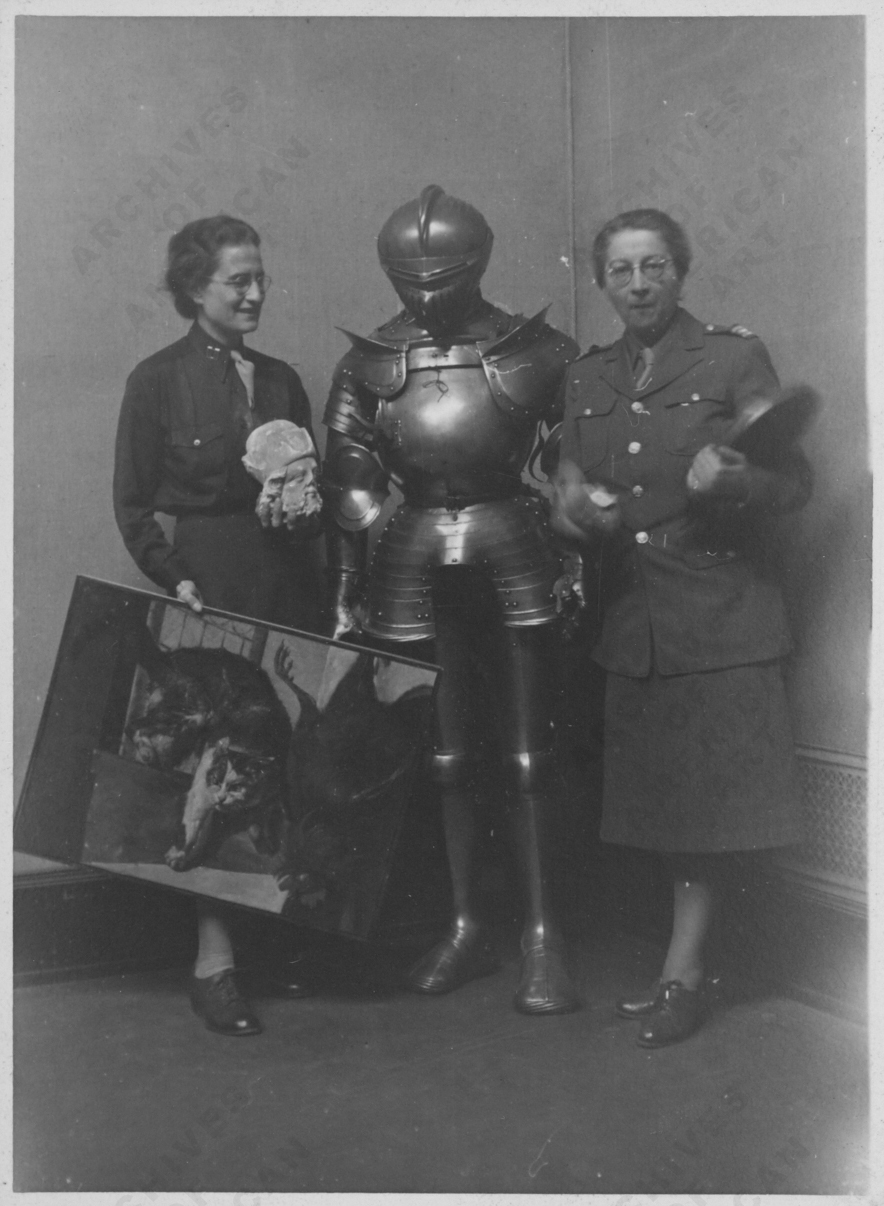

Image: Archives of American Art. “Captain Edith A. Standen and Captain Rose Valland were both MFAA officials. Edith Standen was enlisted as an MFAA officer due to her scholarship (Oxford educated) and art preservation experience (worked at an antiquities preservation society, took Paul Sachs’ museum studies course at Harvard’s Fogg Art Museum, oversaw the transfer of a donated art collection to the National Gallery of Art). During her MFAA service, Standen was Officer-in-Charge at the Wiesbaden Collecting Point, supervising the organisation and restitution of thousands of artworks.”

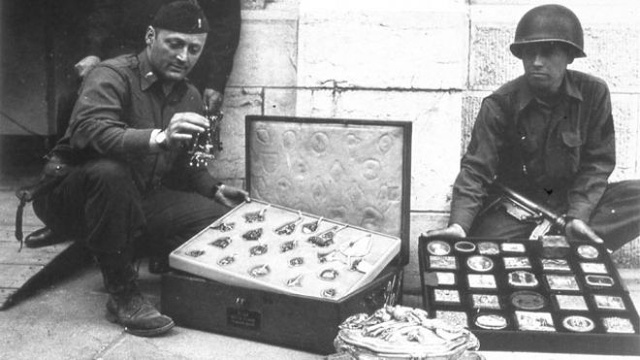

Lead image: This photo provided by The Monuments Men Foundation for the Preservation of Art of Dallas, shows Monuments Man James Rorimer, left, and Sgt. Antonio Valim examining valuable art objects at Neuschwanstein Castle in Germany which were stolen from the Rothschild collection in France by the ERR and found in the castle in May of 1945. AP.