Nobody knows the future. This may seem like an obvious statement, but it bears repeating. Nobody knows the future.

Most people can generally accept this idea. But when it comes to our favourite prognosticator, we often put blinders on. Futurism is an imperfect craft in which the most earnest and educated individual must practice a fair amount of hand-wavy illusion building to even begin the process of prediction. When it comes to futurist-minded people that we like, we’re more willing to remember their hits and forget their misses.

I’ve done a few radio interviews this month about Isaac Asimov’s 1964 predictions for the world of 2014. Everyone wants to know: was Asimov right or was he wrong? And the answer isn’t so simple. Like any vision of the future, even the “accurate” predictions are open to interpretation. And your take on their accuracy probably tracks closely with whether you’re a fan of the man and his work.

From Asimov’s 1964 New York Times article:

Communications will become sight-sound and you will see as well as hear the person you telephone. The screen can be used not only to see the people you call but also for studying documents and photographs and reading passages from books.

There are a thousand different ways to slice and dice this prediction. On its face, this prediction is spot on. But that assessment comes with the biases any person living here in the early 21st century might bring to the table.

A generous reading of this prediction will say that he predicted Skype-like technology. A more sceptical reading of this prediction will look at the dozens of landline videophone predictions from the 1950s and 60s — not to mention the real-world research being done at Bell Labs — and conclude that Asimov was simply repeating a common futurist trope. And that by omitting mention of the infrastructure that would deliver sight-sound telephones — the internet — he really missed the mark.

People have gotten quite defensive about the way that I’ve analysed Asimov’s predictions. And I understand why. People love Asimov. We’re infinitely more forgiving of the people we love, even if we didn’t know them personally. That’s the nature of fandom.

But I’ve tried to put Asimov’s predictions in the context of the early 1960s, and in so doing have pointed out that his ideas were actually pretty conservative for the time. Conservative, in the sense that he hedges many of his bets with little caveats.

Asimov predicted that cars with “robot brains” would drive autonomously at the World’s Fair of 2014. But he didn’t say that they’d be on our nation’s freeways. Interestingly, this hedge made his prediction more accurate. He described robot housemaids in a similar fashion. Sure, they’d be around at the Fair of 2014 — understood by newspaper readers of 1964 as the place to display futuristic technology — but they wouldn’t be quite good enough to work in the average person’s home.

Back in 1964, plenty of people were predicting that driverless cars and robot butlers would be a given 50 years hence. Asimov’s futurist-conservatism paid off in these instances.

But what about the predictions that he failed to slide in caveats for? Asimov also predicted that we’d have moon colonies and cities under the sea. These predictions make perfect sense for 1964. But national priorities shifted over the course of the last five decades. The common refrain, even near the end of the 1960s, was why should we spend money on space exploration with so many problems here on Earth?

Every prediction is a product of its time. Which is to say that futuristic ideas almost always say more about those making the predictions than they say about the actual future.

Futurism is a tough racket. Asimov’s 1964 article didn’t predict the cultural and social upheaval of the late 1960s, nor the rise of the ARPANET (the precursor to our modern internet) that would happen just five years later. And that’s ok.

But once the smoke has cleared, and we’ve done our right/wrong assessment of any given futurist’s predictions, it’s time to ask the harder questions: like “why”? Why would Asimov predict these things? Disregarding whether he was right or wrong about any particular idea, what was going on in 1964 to make those words important enough to print? Why would a colony on the moon or a driverless car be something that Americans of the mid-1960s might care about?

Asking these questions demands a certain kind of objectivity that’s uncommon in futurism. As much as we may love any particular futurist, we must step back and look at the bigger picture. That is, if we want to learn anything about how the future is actually built.

These futuristic ideas and the expectations that go along with them have helped shaped the world we live in today. There’s a certain sense of betrayal seeping through the futurist water supply at the moment. From the Baby Boomers asking “where’s my flying car?” to the Millennials asking “where’s my standard of living?”, we have to look at history to see where these expectations came from. Only then can we figure out how to deliver on those futures.

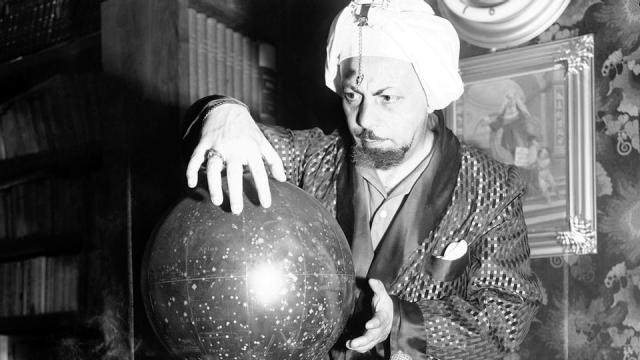

Picture: Professor Lelio Alberto Fabriani, the “Magician of Rome”, in June 27, 1952