In the 1960s, a sociologist named William H. Whyte revealed something interesting about the behaviour of people in parks and plazas across the US: people liked being with people. But has that changed now that everyone carries a tiny computer in their hands? According to a new study: no.

Throughout the ’60s and ’70s, Whyte’s work took him to cities across the United States, where he looked at where people sat and how they interacted with existing features such as fountains — he was even able to examine what environments encouraged more deviant behaviour, like drug use and sleeping in parks. Even in the most dangerous, inhospitably designed places, people would inevitably find a way to use the public space.

Footage shot by PPS in 1980 of the northwest corner of Bryant Park, in Manhattan

His work, named the Street Life Project, spawned the book The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces as well as the nonprofit Project for Public Spaces, which conducted similar experiments throughout the 70s and 80s using his methodology. Planners and architects now look at Whyte’s work when designing these kinds of public places to maximise interaction (and, likely, to discourage drug use and sleeping). It could be argued that Whyte’s studies helped our cities to become radically redesigned to encourage more people to hang out in public instead of inside their houses or offices.

Fast forward to 2007, when Keith Hampton, a professor at Rutgers who studies how technology impacts daily life, attended a PPS event and found himself fascinated by Whyte’s work. He set out to re-create several of the shots to see if the way we interact in public space had changed in the age of smartphones, picking three locations in New York, Boston and Philadelphia. He spent a total of 2000 hours looking at the films with his research team, coding people according to their sex, group size, how long they stuck around and phone use.

Hampton had at least one well-documented exploration of technology and social habits: One of Hampton’s first studies looked at Toronto residents from 1997 to 1999 who had installed internet in their house versus those who had not, according to a New York Times article:

Hampton found that, rather than isolating people, technology made them more connected. “It turns out the wired folk — they recognised like three times as many of their neighbours when asked,” Hampton said. Not only that, he said, they spoke with neighbours on the phone five times as often and attended more community events. Altogether, they were much more successful at addressing local problems, like speeding cars and a small spate of burglaries. They also used their Listserv to coordinate offline events, even sign-ups for a bowling league. Hampton was one of the first scholars to marshal evidence that the web might make people less atomized rather than more. Not only were people not opting out of bowling leagues — Robert Putnam’s famous metric for community engagement — for more screen time; they were also using their computers to opt in.

It turns out this theory holds the same for those who use their smartphones in public — kind of:

It turns out that people like hanging out in public more than they used to, and those who most like hanging out are people using their phones. On the steps of the Met, “loiterers” — those present in at least two consecutive film samples, inhabiting the same area for 15 seconds or more — constituted 7 per cent of the total (that is to say, the other 93 per cent were just passing through). That was a 57 per cent increase from 30 years earlier. And those using mobile phones there were five times as likely to “loiter” as other people. In other words, not that many people are talking, or reading, texting or playing Candy Crush on the phone, but those who do stick around longer.

It’s here that I wish Hampton had some kind of additional, empirical data about who was playing Candy Crush vs. emailing, because I think that’s a very important distinction. I would argue that the number of people reading or playing games alone in public has probably not changed over the years, just the way they do it — magazines vs. e-readers, crossword puzzles vs. apps — has changed.

The spike in people with phones who are hanging out longer is more likely due to texting, emailing, or calling other people in public spaces. Smartphones “enable” us to stick around longer in public because they’re now an extension of our private spaces. Having the phone with us allows us to answer emails and return calls — tasks we used to have to be in the office or back at home to do. In a way, we’re making certain aspects of our private life more public.

Whyte’s study clearly showed a truth about great urban spaces: people loved being in public because they could watch and potentially engage with other people. Hampton’s follow-up illustrates an interesting dichotomy: people still love being around other people physically, even if they ones they’re actually interacting with are nowhere in sight. [New York Times]

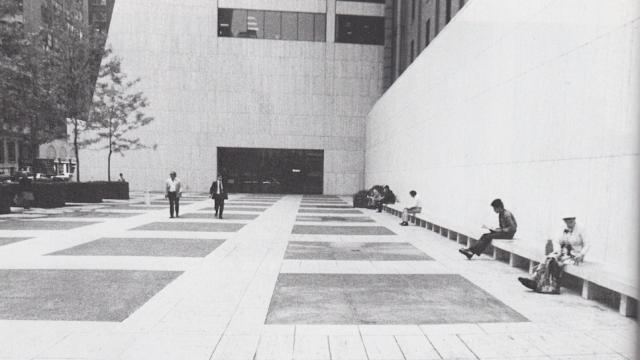

Top image: From Whyte’s The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces