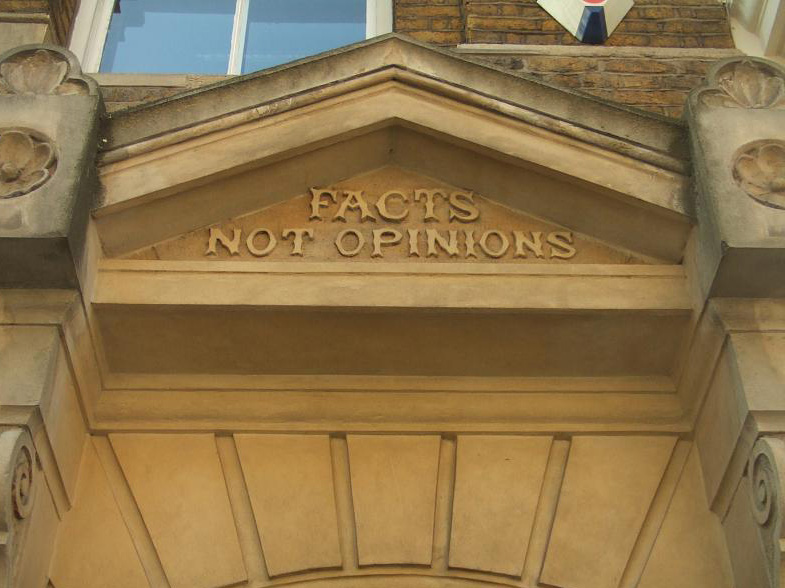

The Kirkaldy Testing Museum in London was where materials were sent to die: to be tested to their breaking points, often pulverised, shattered, broken in two from sheer strain, punched clean through or stretched — ripped and shredded — by hydraulics.

Founded in 1874 by David Kirkaldy, a Scotsman, the assemblage of machines began its life as an actual testing workshop, an internationally known and trusted site for pushing materials to their limits. The machines on display range from a 27,000kg tension-compression machine to a parachute-testing device, a shock-loading “Izod machine” to something called the “Cement Dogbone Briquette Machine” used for assessing the quality of concrete.

Photo by Matt Brown/Creative Commons

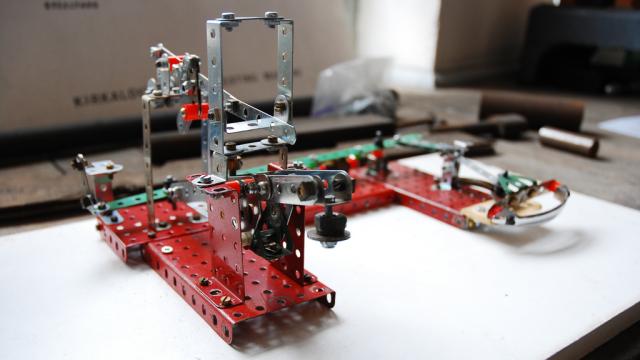

Kirkaldy himself had a kind of ultimate fantasy: a universal device or all-purpose testing machine that could find the breaking point of anything it encountered. Described this way, Kirkaldy’s universal testing apparatus nears the status of metaphor: a device that can find and exploit the vulnerabilities in any other machine or material it comes into contact with, implying that we should be as familiar with the phrase “Kirkaldy machine” or “Kirkaldy device” as we are with, say, a Turing machine.

The reality is a bit more prosaic, however, encompassing an actuator, testing abilities for tension and compression, and the ability to shear, crush, and twist other materials to the breaking point. This machine-that-could-outmachine-other-machines, this metaphor in the making, has also been modelled in miniature, as seen in the lead photograph, above.

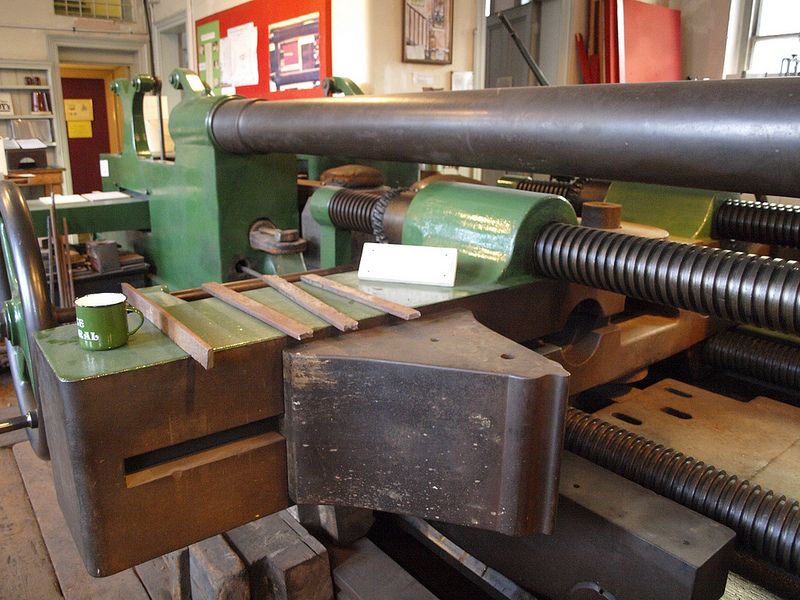

But I first read about this museum in a recent issue of the excellent music magazine The Wire. There, Louise Grey describes the simple but brilliant idea to turn the Kirkaldy Testing Museum into a kind of machine orchestra, an assemblage of resonant, vibratory, and percussive devices shuddering and clanging with their heavy metal symphony, all captured on well-placed microphones.

The experimental music — conducted as part of the Merge festival — began, Grey writes, when the “testing equipment was wired, springs fitted with contact mics and wooden blocks and concrete cubes were pressed and pulverised.” Like the prepared pianos of John Cage, this was a prepared factory, a prepared abattoir for destroying the material world. The results included “warm, reverberating sounds and the occasional explosion of a piece of wood shattering.”

Photos by Ann Gav/Creative Commons

“Much of the workshop,” Grey summarizes, “was transmogrified into possible sound sources. Objects were strung and sprung, tampered with and amplified in various ways: concrete cubes crumbled with faintly audible sighs and timber was broken apart…. The ensuing sounds were never violent: oscillations aped the noises of saws and drills and the echoing clunks of amplified springs produced overtones that bounced off all the ironware. There were the ghosts of an industrial past made audible for our times.”

Quite possibly speaking only for myself here, there are many interesting aspects to this, not least of which is the very premise of the project: finding, amplifying, and coordinating everyday sound sources into literally industrial music, and thus revealing the background sounds we normally tune-out, that we soften through urban noise regulations, or that we dismiss as an annoying nuisance without ever really listening in the first place.

The point, of course, is not that we should be forced to hear industrial sounds all the time — that we should make ourselves deaf or stressed-out, listening to machines clack, buzz, and whir — but that, every once in a while, cutting down through the often misleadingly peaceful ambience of everyday life to hear the mechanical inferno that makes our world is a refreshing reminder of the strength and vitality of base materials, things we’ve tried so hard to domesticate.

Even if only for the duration of a music festival, then, whatever we can tolerate, we should let the discord roar.

Lead image courtesy Yiping Lim/Creative Commons