Last month, at a two-day event in London, U.S.-based nonprofit CyArk announced its goal to digitally preserve 500 heritage sites in just five years. It’s an ambitious plan to ensure that future generations can explore the world’s most at-risk heritage sites for centuries to come — but, in reality, the future of preserving the past is actually all about you.

For all the talk of 3D laser-scanning the ancient world in fine detail, the truth is that there’s more to preserve than just the 500 sites targeted by CyArk. There are tens of thousands of buildings that need to be scanned and catalogued, if we’re to do a proper job, and that’s before you even think about small, individual artefacts as opposed to large structures.

Museums around the world are home to millions of objects that could easily degrade or be destroyed over time — and that could just as easily, perhaps even preferably, be viewed and visualised in digital 3D. The Smithsonian alone has capturing them in 3D, the truth is that this is too big and expensive a job for them to imagine accomplishing alone.

That’s where you, me, and future generations come in — in terms of generating data and consuming it, too.

Capturing the Past

It’s surprisingly easy to capture 3D models of small everyday objects using little more than your phone and some patience. Autodesk’s 123D Catch, for instance, leans on a technique called photogrammetry to make use of your iPhone’s camera and processing grunt to create 3D models of real objects. Essentially, it infers geometric properties of an object from a series of photographs taken from different angles.

It’s not a new idea — in fact, the theoretical principles of photogrammetry have existed since the birth of photography — but the ease of application is now made possible by the tiny computers we all carry around in our pockets, all day, every day.

The fundamental concept behind photogrammetry is that of triangulation: by taking photographs from at least two different locations, it’s possible to create lines of sight which allow the position of points on the object to be determined in 3D space. Clearly, the more photographs, the better the results — as errors can be smoothed out and noise reduced. That makes the technique well-suited to small objects, where it’s possible for a single user to take many images from multiple angles in just a few minutes, before dumping them into a program like 123D Catch to create a 3D model.

“People are really excited by the possibilities of technologies like 3D printing, augmented reality, and 3D on the web, but since most people aren’t CAD experts the problem has always been where do you get the 3D models from?” asks Brian Mathews from Autodesk. “With tools like 123D Catch anyone create a 3D model of a heritage site, a priceless fossil, or their favourite pet. With over 55,000 museums in the world, there is a real opportunity to crowdsource 3D capture our collective heritage and get it online for everyone’s benefit.”

In fact, Gizmodo has already explored how kids — awesomely — are now able to use it to create 3D models of dinosaurs.

But let’s get more ambitious. Apps like 123D Catch can be used to create far larger models given enough photographs. Fortunately, many of the heritage sites that the likes of CyArk want to capture also handily double as attractive tourist destinations — where people tend to take bucket-loads of pictures. If you could aggregate all the images captured by snap-happy holiday-goers, you could use the same process to construct 3D images of entire buildings, not just small exhibits.

Which is exactly what Autodesk is doing with something called Project Memento. “Project Memento can work with the truly massive data sets you get from reality capture — from lasers or plain old photos — and clean them up. It has some of the functionality of out other software, but it works on much, much bigger data sets,” explains Matthews. The results, so far, aren’t perfect — but they’re certainly impressive, given the sprawl of data that the algorithms have to put up with.

However, if crowdsourcing can’t supply all the data we need, another option is available: child labour. OK, that’s a bit of a stretch — but, when it comes to getting everybody involved in the process of capturing reality, even school kids are getting involved. The CyArk project, for instance, recently partnered with the Mid-Pacific Institute in Hawaii, where students, guided by the school’s president, Dr Paul Turnbull, have been using a Faro Focus3D scanner, to capture local heritage sites in all their 3D glory.

Perhaps the best thing about the work at the school is the spirit it instils in the students. “Reality capture is a powerful tool for the younger generation to preserve our cultural heritage locally, while also building stronger contextual understandings of global cultures and histories,” explains Dr. Turnbull. “The best part is of this scenario is the unknown: how will the collective creativity of the younger generation of students around the world apply this technology to make the world a better place? Personally, I feel like I have a front row seat to the most exciting time in education for at least that last 100 years.”

Back to Reality

Fortunately, all the hard work that you and your spawn are set to do should pay off. After all, these digital records aren’t being collected simply to be stored away on disk; rather, they’re being created so they can be visualised, consumed, and used.

This is democratised data, to be shared and enjoyed by all.

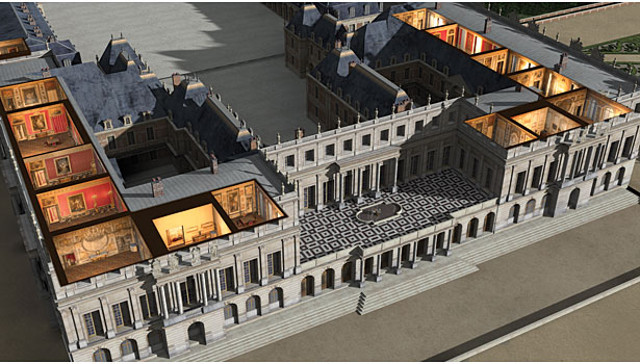

Take, for instance, data captured by Trimble at the Palace of Versailles. Having digitised the entirety of the the massive French chateau — all 67,000 square meters of its floorspace, over 2,300 rooms — the resulting data was painstakingly converted to a super-detailed 3D model in Google’s SketchUp. Adding high-resolution images of pictures and detailed renderings of furniture and sculptures has provided an amazing, explorable environment.

This means the Palace can be explored in a way that’s totally different to wandering around its rooms and corridors in real life: you can pull away walls and ceilings, and peer inside the gigantic palace as if it were a doll’s house — but with the ability to zoom in and see real details, too. It’s not a replacement for visiting the place itself; it’s a complement. But in many ways, the digital version is better; at the very least, it is far more interactive.

That’s just one space, though. If Google has its way, each and every landmark, museum, and gallery could be mapped out in glorious 3D detail. To an extent, that’s already happening with its Cultural Institute. Using a combination of Street View and high-res images, that initiative already allows users to explore museums and heritage sites all over the world, from the National Gallery in Prague to the structures of Stonehenge, allowing you to take a close look at historical objects and learn about them in great detail.

But, in the future, you can expect the contents of the Cultural Institute to become far more rich — featuring 3D models that you can (digitally) pick up and admire, in a way that you’d never be able to in a museum.

Some argue, though, that 3D models are not enough. “We are often told that in order to discover something new, we must study the old; to know the future we must understand where we came from,” explains Prof. Dr. Sarah Kenderdine, National Institute for Experimental Arts, College of Fine Art, University of New South Wales. “But new imaging technologies alone are not enough to preserve the multifaceted essence of a culture. Our challenge is to bring cultural objects and places to life in ways that are profound, and unforgettable.”

Which is why Kenderdine is at the forefront of developing museum exhibitions, such as the school’s iDATA program, that allow people to explore the 3D environments created from data acquired by CyArk.

One of her exhibition designs, for example, uses iPads and a raft of IR cameras to show users what would be immediately in front of them as they move the tablet around in space, displaying a 3D environment in what is, essentially, an empty room. Elsewhere, similar techniques allow users to point a virtual “torch” at a wall, prompting projections to reveal what would usually be concealed by darkness.

These are expensive, high-tech installations, to be sure, but they bring digital data to life and open up a world of history to those who may never have been able to explore it.

“The future for interpretation does not have to rely on a multitude of texts; it is necessarily more open and more democratic. Experiences need to be designed that touch both young and old, literate and those that are still learning,” explains Kenderdine. “Interpretation cannot be fixed. Interactive technologies help us achieve these new interfaces to the world around us, helping us rediscover and reinvent.”

The future of the past, then, is quite literally in all our hands.