How is this possible? The American Institute of Architects, the largest and most influential architecture organisation in the US, had never, ever awarded a Gold Medal — its highest honour, which it has been bestowing upon architects since 1907 — to a woman. Until now.

I only really have one question here.

What took so long?

The woman in question is no doubt worthy: Julia Morgan was the first female architect licensed in California and had a long and influential career, designing over 700 buildings. She is best known as the designer of Hearst Castle, collaborating for 28 years with the mercurial William Randolph Hearst.

But she also designed dozens of YWCAs in California, including the the Asilomar conference center near Monterey; many private homes; and the gorgeous (and currently vacant) Los Angeles Examiner Building in downtown LA. She majored in civil engineering at Berkeley and was an early expert in reinforced concrete construction methods, which came in especially handy after the 1906 San Francisco earthquake.

The Oakland YWCA, designed by Morgan in 1915, photo by Sanfranman59

It was a female AIA board member, Julia Dohono, who nominated Morgan after realising the Gold Medal had never gone to a woman. She nominated Morgan because she felt that the organisation needed to go back and recognise Gold Medal-quality women who were “overlooked,” she tells Karrie Jacobs in Architect.

But this sentiment has not been particularly well-recieved by the architecture community, many of whom perceive the move as “too little, too late”. Over at Metropolis, Martin Pedersen says that what may have been an attempt at a political statement simply came off as tasteless: “The award felt less like the honour it is, or was, and more like a backhanded compliment from a socially awkward but well-meaning relative.”

But why did it take so long?

One could argue that there were fewer women in the field until a few decades ago, and you’d be right — up to a point. Morgan was the first woman to attend the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, an influential French school that trained many architects at the time. But that excuse quickly becomes invalid. The AIGA — a similar professional association for graphic designers which has been around almost as long as the AIA — first gave its medal to a woman in 1967, and has since honored 24 more. It is obvious in recent years that they’ve made a great effort to correct their oversight.

When the AIA revised its rules this past summer so that a duo, not just a single practitioner, could win a Gold Medal together, everyone assumed that the organisation was prepping its own heroic response to a media firestorm about another architecture award, the international Pritzker Prize. Last spring, Harvard architecture students had just launched a petition demanding that Denise Scott Brown, wife and architectural partner of 1991 Pritzker winner Robert Venturi, also be acknowledged by the Pritzker jury, retroactively. The Pritzker committee said no.

The AIA’s new “duo” rule goes into effect January 1, and I think this means that next year the AIA will honour Venturi (who has never received the Gold Medal) and Scott Brown together, somewhat righting the Pritzker’s wrong. Yet even the Pritzker — which, yes, has different criteria, but has honored many of the same American architects — has given its prize to women twice: Zaha Hadid in 2004, and the female half of the duo SANAA, Kazuyo Sejima, in 2011.

So, really, what took so long?

On Thursday, an exhibition opened here in L.A. that examined the early career of Deborah Sussman. The influential 82-year-old designer got her start in LA working for Charles and Ray Eames, and created the transformative graphics for the 1984 Summer Olympics.

Architect Barbara Bestor, who co-curated the exhibition, told me that one of the reasons they organised the show was to drum up attention online and in social media in the hopes that more potential fans would discover Sussman’s work. “If you’re not on Wikipedia or have a show that creates stories that exist in the current form of media, you basically don’t exist because nobody goes to the library anymore,” Bestor told me. “Curating is a good way to do that.”

Deborah Sussman in 1965 and members of the Eames Office wearing glasses she designed for the 4th of July

What Bestor told me stuck in my head for the next few days. In recent years, we’ve seen the “revival” of some other female designers, like furniture designer Greta Grossman, who was rescued from obscurity when Design Within Reach put some of her furniture back into production. Or screenprinting artist and nun Sister Corita Kent, who was rediscovered after a film and series of books celebrated her work.

The sad truth is that so many legends of design and architecture are only, largely, known to other practitioners of design and architecture.

Seriously, why did it take so long?

I ran into one of those design legends at the farmers market Saturday morning: Gere Kavanaugh, an industrial designer who worked at GM in the 1950s before moving to L.A. to design furniture, textiles and interiors. “I just found out I’m not on Wikipedia,” she told me, so she was headed to an event organised by L.A.-based online art magazine named East of Borneo called Unforgetting LA. It was a hackathon of sorts, inspired by an article by Despina Stratigakos, one that hoped to populate Wikipedia with more female designers and architects, namely those working and practicing in Los Angeles.

A dozen volunteers gathered at the MAK Center, housed in the former home and studio of modernist architect R.M. Schindler, where they were briefed on Wikipedia’s style and coding language. “Everyone there had brought their own laptop and was hard at work,” architect Rachel Allen told me. “Once you start poking around a bit, it’s pretty shocking the women who don’t have even a nominal presence on Wikipedia.”

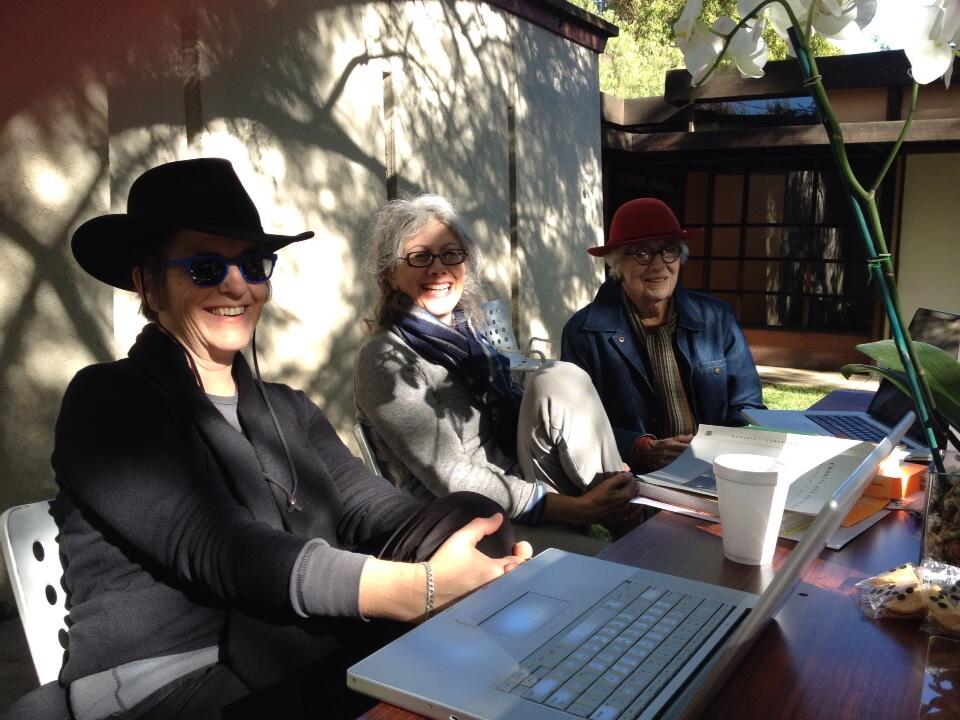

Kimberli Meyer, Louise Sandhaus, and Gere Kavanaugh at Unforgetting LA, photo by East of Borneo

Designer Louise Sandhaus, who is working on a book about California design, was impressed by how much she got out of the day. “There was this group working together proactively to get this rich history of women architects and designers included and accessible,” she said. “But there was also the ‘live feed’ of finding out about designers I didn’t know about.” Kavanaugh showed up at the event just as MAK Center director Kimberli Meyer was editing her entry.

Thanks to the efforts of this group, Kavanaugh now has a Wikipedia page. So does Sussman. So do many other female architects, like Brenda Levin and Dana Cuff.

Once upon a time, like Bestor said, people discovered designers and artists and architects and other creative types through books, and maybe the odd magazine or newspaper. Discovery is different now. Now, unless a designer’s work happens to be published on a design blog, or pinned to a Pinterest page, or posted in an influential Instagram account, it doesn’t have a visible foothold in contemporary culture. It doesn’t stay top of mind. And it never gets introduced to a new generation. In today’s search-optimised world, if the first page of hits doesn’t give a complete picture of who the designer is, the searcher is likely to move on.

Which brings us back to Julia Morgan

Morgan — who does have a Wikipedia page, by the way — absolutely deserved the Gold Medal. She deserved it much sooner, but it is a good first step by the AIA to try to correct this oversight. The problem now becomes that there are so many other worthy women to honour, and the AIA can only award one medal per year (technically two, if to a duo).

So here’s what the AIA needs to do, which will require at least two more amendments to their rules:

- The AIA should award at least two medals per year, to two individuals, one individual and one duo, or two duos.

- The AIA should actively try to diversify their awardees. This doesn’t just mean women. It also means looking at diversifying the AIA’s list in other ways, like Paul Williams, the first African American architect to be certified west of the Mississippi.

If these things don’t happen, the AIA is going to spend the next decade or so attempting to randomly slot all the “overlooked” women before they start honouring contemporary ones. This will take forever and will also lead to a cycle of honouring dead women and living men, which sends a very, very bad message. (Morgan had a better post-mortem win rate than only one other honoree: Thomas Jefferson, who received the award in 1993).

The point of these awards is to honour these practitioners while they’re still alive, to point out that what these architects are doing matters right now, not a half-century ago. (If lasting legacy was the point, they’d have statues of limitations like the Rock’n’Roll Hall of Fame.) But another by-product of awards like the AIA Gold Medal and the Pritzker Prize is to vault these winners into the highest echelons of the contemporary media conversation — back into collective online consciousness.

These awards and sharable links of legitimacy — including that all-important Wikipedia page — will help keep these practitioners alive long after they’ve left us. But these things have to start happening while these designers are still here.