Decades before molecular gastronomists were hocking vodka mist and caviar foam, we had food that was just plain fun: Pop Rocks, Magic Shell, and countless other strange creations that required a science lab to invent.

We took a look into the origins of these wacky treats, and what we found were lab experiments gone wrong, bizarre patent applications, and tons of illicit basement chemistry. Read about three of the most interesting stories below, from the lab accident that spawned Pop Rocks to the unquenchable American thirst for frozen booze that spurred the margarita machine.

Pop Rocks

During his 35-year career as a famed food chemist at General Foods, William Mitchell registered at least 44 patents and invented dozens of ubiquitous foods, including powdered eggs, Jell-O, and Tang. He was also responsible for dozens of lesser-known curiosities, like ice infused with carbonation and an 140-proof alcohol in powder form.

Mitchell’s best known invention was actually a food chemistry failure. In 1956, he was toying with transforming carbon dioxide into solid sugar. The idea? To develop a carbonated drink powder. But Mitchell’s gas-infused lumps fell flat — at least where soda is concerned. One day during a taste test, though, the project took a turn for the Willy Wonka-esque. A bit of the powder made its way into Mitchell’s mouth, where moisture from his saliva caused the carbon dioxide to pop and fizz. Today, most of us would recognise the explosive sensation as Pop Rocks.

It was an immediate hit among the food science set. In an interview with People Magazine in 1979, Mitchell explained that “it became a game — who could swallow the biggest chunk. It was a fun afternoon and we wasted a lot of time, but I thought it was a good thing from the start.”

It may have been a hit with scientists, but food that explodes wasn’t the most intuitive sell. Mitchell’s crystals utterly stumped the General Foods marketing and mass production departments, and the product was shelved for nearly two decades. (Meanwhile Pop Rocks were still a lively presence in Mitchell’s social circle — he enclosed them in his family’s Christmas cards for years.)

In 1974, though, a Canadian subsidiary finally put Pop Rocks on shelves, promoting them as a gag. The US market caught on two years later, and enthusiasm for the rocks hit the sky. By 1978, 500 million packets had been sold.

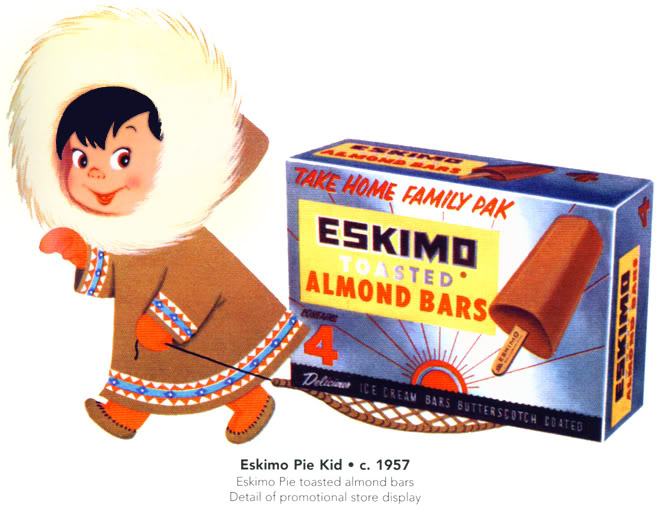

Eskimo Pies and Magic Shell

The story of the chocolate covered ice cream bar starts in a tiny confectionery shop owned by Christian K. Nelson of Onawa, Iowa in 1920. According to the Smithsonian, a boy came into the shop and “started to buy ice cream, then changed his mind and bought a chocolate bar. Nelson inquired as to why he did not buy both. The boy replied, ‘Sure I know — I want ’em both, but I only got a nickel.’”

That eternal conundrum — hey, we’ve all been there! — sparked a delicious idea, and Nelson quickly took to his home laboratory in search of a way to combine chocolate bars and ice cream. Now, anyone with ice cream sundae experience knows that melted chocolate poured over and frozen ice cream quickly turns into a messy puddle of goo. Was it possible for chocolate and ice cream to co-exist without compromising the integrity of either?

After much experimentation, Nelson finally found the answer in cocoa butter. It turns out that the cocoa bean’s fat is unique, in that it’s rigid at room temperature, but melts just below the temperature of our bodies. In other words, it’s easy on the ice cream. The butter proved to be the perfect adherent — so much so that Nelson immediately (and successfully) poured his new-fangled chocolate sauce over 500 bricks of ice cream, which were beta tested at a fireman’s picnic. The positive response prompted Nelson to partner with Russell C. Stover, the Chicago-based chocolate maker, in order to get his invention to market. Within the first 24 hours, the team sold 250,000 units of what they’d rebranded as the Eskimo Pie.

Image via.

Eskimo Pies turned out to be the precursor to another ice cream innovation, too: Magic Shell, the syrup that transforms from a liquid to a solid within seconds of hitting the soft serve. It’s not really so much magic as science; Magic Shell employs a fat-filled ingredient that, like cocoa butter, freezes easily but doesn’t require much heat to melt. Other brands have replaced that oil with similarly unconventional ingredients: For example, Mister Softee employs an “edible-grade paraffin wax.” Mmm.

The Slurpee and the Frozen Margarita

When Omar Knedlik purchased a Dairy Queen franchise in Coffeyville, Kansas in the late 1950s, his location lacked a soda fountain. So he faked it. To chill cola quickly, Knedlik used the freezer. It was an imprecise system, and customers would sometimes end up with half-frozen drinks — just the way they liked it.

His freezer trick was a hit, but kind of a pain to manage, so Knedlik began experimenting with machines that would simplify the process on a larger scale. In his 1958 patent for a “Process for the Preparation of a Beverage,” Knedlik details a cold, hermetically-sealed chamber that’s kept under superatmospheric pressure to maintain carbonation. Inside, the ingredients — CO2, flavored syrup, and water — would need “vigorous and continuous” agitating to preserve a constant slushy state.

The machines were purchased by 7-Eleven in 1965, where they served to chill the chain’s ubiquitous Slurpee. And six years later, they inspired another invention in Dallas, Texas, where a local inventor and restaurateur named Mariano Martinez was struggling to keep up with demand for his blended booze cocktails.

One day, on a coffee run at the convenience store, Martinez had an epiphany: why not use the Slurpee machine for alcohol? The only hitch, unsurprisingly, was that the convenience store refused to sell him a machine. So Martinez — just like Knedlik and so many other food chemists — elected to build his own. Using a modified soft-serve ice cream maker, Martinez engineered an frozen margarita machine that served 34 years of duty, churning out tequila slush until it was inaugurated into the Smithsonian’s collection, in 2010.

So there you have it: A little frustration, an adventurous palate, and a whole lot of tinkering can spark some surprisingly far-reaching inventions. Just stay away from the cinnamon challenge, ok?

Lead image, from left to right, via Pepper.Ch and 52 Kitchen Adventures.