Last month, a blog post by Sam Cookney captured the imagination of anyone who pays a little too much money for the convenience of living near work. He reasoned that, for the same price he paid for his one-bedroom London flat, he could live in a three-bedroom flat near the beach in Barcelona and fly to work in London four days a week. And he’d still have 387 Euros left over at the end of the month.

If you put it that way, extreme jet-setting scenarios like this sound like a pretty amazing idea. Even if it’s really just a fancy way of commuting to work, the thought that we could be sitting at our desk in London and then, just hours later, be sipping rioja on our balcony overlooking the Mediterranean, is still impossibly awesome. Who wouldn’t want to make enough money in one city and be go home to a place where you can actually enjoy it, even — or especially — if it’s a few hundred miles away?

Of course, there are two factors here that make Cookney’s maths specifically feasible. First, London is a catastrophically expensive city — just check out this depressing London rent calculator by the Financial Times that shows the percentage of your salary you’d have to spend on rent — so living practically anywhere else would save you money, comparatively. And, second, Ryanair, the airline Cookney used in his calculations, is a ridiculously cheap carrier notorious for being heavily subsidised by European airports.

But Cookney’s proposal is not altogether unrealistic. The book Aerotropolis: The Way We’ll Live Next traces how these low-cost airlines changed the commuting patterns for Europeans. A study by Future Forum predicted that, by 2016, there would be 1.5 million people who work in the U.K. but commute by plane from their homes overseas in cities like Tallinn, Marrakech, and, yes, Barcelona. Cookney’s fantasy is a reality for a growing breed of supercommuters — dubbed aerial commuters — who take planes to work.

According to a 2012 study by the Rudin Center for Transportation at the Wagner School of Public Service at New York University [PDF], supercommuting is on the rise; in the “Texas Triangle,” between Dallas and Houston, it’s estimated that supercommuters actually make up 13 per cent of the workforce.

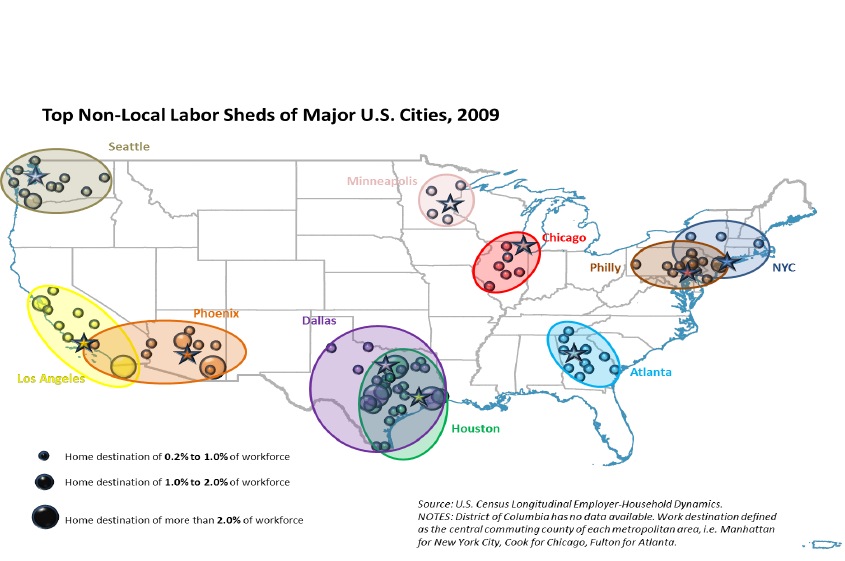

This trend is creating radically different “city labour sheds,” where the people who work in a city live not just in nearby suburbs and exurbs, but also in distant metropolitan areas that are sometimes hundreds of miles away. Due to aerial commuting, parts of Northern California are now part of L.A.’s city labour shed, for example. In a sense, being able to fly to work, at least some of the time, means that our cities — or, at least, the economic footprint of them — are growing in vastly different ways.

In the U.S., these aerial commuters who are famous for racking up celestial numbers of frequent flyer miles are known as “road warriors” (I know, it should really be “sky warriors”). They’re likely to be white males, married but without children, and making about $US78,000 a year. The best fictional example of a road warrior is probably the Ryan Bingham character in the book Up in the Air, portrayed by George Clooney in the film. But there are very real and (almost) normal-seeming examples. From Aerotropolis:

Matthew Kelly’s commute is a weekly routine. A married 30 something consultant for AlixPartners — the ones tasked with disposing of General Motors’ spare parts — Kelly awakens each Monday at 4:00 a.m. in his Brooklyn apartment, showers, dresses, and slides into a waiting taxi at 4:30, arriving at LaGuardia by 5:00. He slips through security and boards a flight at 5:30, landing in Atlanta or Wichita by 8:30 and gliding into the client’s office an hour later. He travels light, packing only his laptop, not stopping to pick up fresh laundry from the dry cleaner until he’s on his way to the hotel. Three days later, he catches a four 40 flight home. Thursday night flights are known as “consultant expresses,” and there are never enough seats to check everyone’s egos into first. Barring delays, he’s on the ground by 7:00 p.m. and home (if you can still call it that) in 30 minutes. Fridays he works from Manhattan; he spends weekends on the couch.

OK, I know the first thing you’re going to say: This sounds HORRIFIC. Being on a plane for an hour or two is usually fine. But who in their right mind would want to spend several hours per day, or even per week, getting to and from that plane? Going through security can be at least an hour-long predicament. Plus, you’ve got to navigate the traffic from your home to the airport — not to mention the inevitable flight delays. Anyone who has tried to fly somewhere and back in the same day knows it’s simply not a pleasant experience.

There are some recent advances that have made aerial commuting more pleasant. The proliferation of in-flight wifi and, now, not having to turn off your electronic devices allows you to keep working so you don’t lose as much time in the air. And services like CLEAR or the TSA’s PreCheck can expedite the security process, saving you some time on your way to the gate.

But the real problem is the U.S. airline system itself, says Greg Lindsay, co-author of Aerotropolis. “Hubs and spokes are great for long distances, but not for daily frequencies — their size, cost structure, and the hassle of security are simply too much of a pain,” he says. “We need the equivalent of taxis — or at the very least, Uber — with smaller airports, no security, and flights you could step onto as if boarding a bus or train.”

One idea for an air taxi that could disrupt that hub-and-spoke system was proposed by a Florida company called DayJet, which Lindsay wrote about in 2007. It actually “operated” virtually for several years as transportation modelers tried to figure out, theoretically, when and where the service would fly. But the biggest issue was determining how much those flights would cost — it was impossible to offer accurate pricing because modelers couldn’t figure out how to generate ticket prices as quickly as, say, Orbitz, or more critically, a rental car company. It eventually succumbed to the 2008 financial crisis. Another service named Blackjet, which was actually being billed as an “Uber for private jets,” and worked by booking passengers on empty private jet seats, just ran out of money.

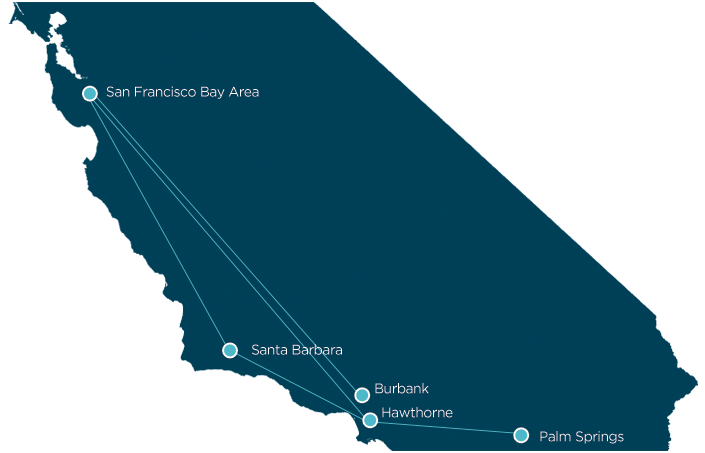

What actually might work is a new company called Surf Air, which will begin operations next month. Similar to DayJet, Surf Air operates a fleet of tiny planes outfitted with private jet-level perks. A membership starting at $US1,350 per month gets you unlimited flights on a schedule made for commuters. Because its passenger numbers are small, it qualifies as a charter service in the TSA’s eyes, so no advanced security screening is necessary. But here’s the key: You wouldn’t be flying out of big airports like LAX or SFO. You roll up to tiny Hawthorne Airport, south of L.A. at 6:00 a.m., and after a quick stop in Santa Barbara, you’re landed at San Carlos Airport at 8:40 a.m., right in the heart of Silicon Valley.

For some supercommuters, Surf Air might make sense but, in the near future, it’s more likely that a replacement for flying will soon serve those people travelling between 50 and 250 miles to work. High-speed rail (or a Hyperloop!) will eventually close that physical distance, and transport us from urban center to urban center instead of simply dropping us at a distant airport.

But the bigger trend, of course, will be that increasingly mobile lifestyles — be it from cheap air taxis, maglev trains, or driverless car share — will grant us the luxury of creating more flexible schedules. Not just the idea of telecommuting or being able to work anywhere, but a change in the way we solve problems of needing to be in two places at once. Instead of finding the best method of commuting to the same place every day or week, the way we measure quality of life will start to change. Back to another example from Aerotropolis that kind of blew my mind:

Consider Angela Kim, who commutes from Houston to Dallas every Tuesday to babysit her grandson for a few days while her daughter the physician pulls back-to-back shifts for her residency. Occasionally she lands, scoops him up at the curb, and boards the next 250-mile, 55-minute flight back to Dallas… Kim’s commute has made all the difference for her family. Her daughter was ready to quit medicine rather than put her son into day care, and she wasn’t about to uproot herself for a permanent move to Dallas. It turns out buying tickets in bulk is more cost-effective than either.

We’re talking about some serious work vs. life calculations here: Traditionally, the parent who wants to make a good living and also have family nearby to care for her son would have to move — or ask her parents to move. But she doesn’t — she’s able to fly in her own mother to act as nanny. The quest for this family’s happiness suddenly becomes less about a salary in one city and real estate prices in another, and more about a simple equation of time and distance. As the population ages, more grandparents will be alive longer to provide these kinds of childcare services, but they’ll also be more likely to be far away, retaining their independence.

The next wave of supercommuters could very well be grandparents, flying out to care for their grandchildren for the week, while parents work close to home.