In today’s Observer, architecture editor Rowan Moore explores Europe’s largest infrastructure project: London’s new Crossrail line. Moore explains that, in addition to such factors as cost, miles, tons of dirt moved, and other construction superlatives, Crossrail also “claims to be the largest archaeological site in Britain, an inadvertent probe through a plague pit, a Roman road, a madhouse cemetery, [and] a Mesolithic ‘tool-making factory.’”

Alongside its stunning slideshow, the piece is full of fantastic details. For example, the construction workers, many of whom are former miners who lost their jobs when the pits closed in Yorkshire and Wales, wear metal tags. Why? This “means they can be identified if incinerated.”

Moore adds: “Miners, I am also told, make the best gardeners, as they want to spend as much of their leisure time as possible in the fresh air.”

Two of the more astonishing architectural achievements are offsite, however — outside of London altogether.

In a brief parenthesis, Moore points out that “in Sheffield, an entire station has been prefabricated for erection in London,” simply awaiting its transfer to the city, where it will be reassembled in place like a puzzle.

However, Moore also mentions the deeply fascinating work of the Tunnelling and Underground Construction Academy, or Tuca, a school for digging really big holes, which is now at the top of my itinerary for any future trip to England.

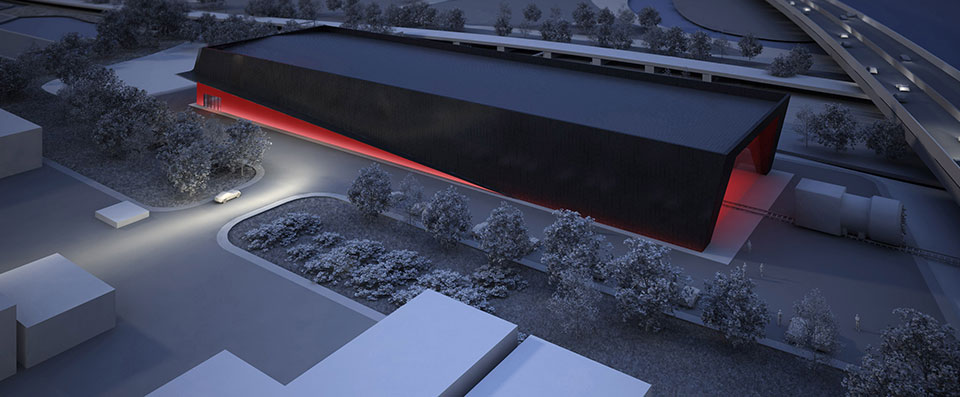

Tuca — as seen in the rendering, above — is “a large hangar-like building in Ilford, Essex,” Moore writes, “the majority of whose cost has been paid for by Crossrail. Here, in a facility that ‘doesn’t exist anywhere else in the world’, full-size mock-ups of tunnel building sites are created, where noise and hazards are simulated.”

This Greater London tunneling academy also has two of the amazing multistory concrete-spraying robots used to line the cavern walls; various facilities, including a “simulated pit top” for training in test-excavations; and week-long intensive workshops for learning tunnel “formwork.” You can also get certified as a “tunnel operative,” picking up the skills necessary for managing underground traffic. Whatever path you take, confined-space training will be part of your coursework.

And it appears that, at least under certain circumstances, you can visit; the school hosted an open house back in September, which included “walking through a 40 meter tunnel mock-up complete with rail tracks and locomotives and a sprayed concrete lining workshop with its robotic equipment and mandrels on static display.”

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of Moore’s article is the way it reveals the incompatible timelines of major infrastructural investments and urban change. In a sense, any city, when looked at through the lens of its infrastructure, is out of synch with itself.

For example, Crossrail’s route seems slightly arbitrary in today’s London, missing a somewhat obvious opportunity to connect to Eurostar or Heathrow’s Terminal 5, as well as to hook up with the areas of largest expansion around London.

Moore suggests that this is because these projects were planned during very different eras in the city’s infrastructural calendar, and Crossrail, in particular, was planned so long ago:

Versions of it were proposed in the 19th century and in the 1940s and the 1970s, before being put forward again in 1989. Parliament deemed it too expensive in 1994 and it was nearly frozen again in 2008, when the looming financial crisis made such huge expenditure look like a bad idea. It is rumoured that it only got through because the then transport minister, Andrew Adonis, also an enthusiast for HS2, slipped it under Gordon Brown’s nose when the prime minister was distracted by thoughts of holding a snap election. According to Tony Travers, an expert in London planning at the London School of Economics, “putting the funding together took years and required valiant efforts by London First and the City of London Corporation. The government had to be lobbied for nearly two decades.”

Travers adds: “Crossrail is an example of the odd way we plan projects. In brief, either you get this one big project or the money disappears. There is never an alternative use for the public resources. It is very hard to be sure about value for money. Having said that, major railways in London or the south-east are almost always going to give better cost-benefit figures than the same project anywhere else in the UK.” In other words, Crossrail is being built not because it is definitely the best way of spending the money, but because it was so large and so persistently put forward that the government grew tired of saying no.

You should read the article in full for many other fascinating details of near-misses (an 80 centimeter brush with the Northern line), property values, art commissions, and more. [Observer via Studio-X NYC]

All images — which depict Crossrail excavation sites, not the facilities of Tuca — are courtesy of the Crossrail press office.