Dan Barasch, the co-founder of the Lowline, gets calls all the time from people who think his underground “culture park” already exists. In fact, the project’s successful 2012 Kickstarter campaign was only the first step in the old-fashioned process of politicking, fundraising and engineering. A year later, a look at the renderings versus reality, and the ongoing question of what exactly the Lowline will be.

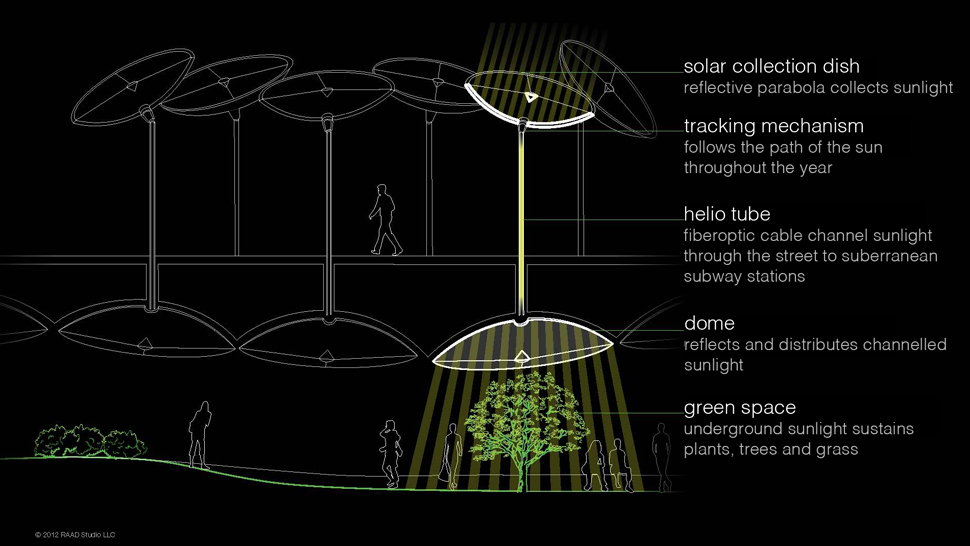

St. Patrick’s Old Cathedral on Mott Street was standing room only on May 3 for Pitching the City: New Ideas for New York. Co-sponsored by old-guard Municipal Arts Society and new-guard social-networking site Architizer, the event offered the founders of five urban initiatives the chance to present their projects, TED Talk-style, to a roomful of interested urbanists and a panel of judges. First up, Dan Barasch, co-founder (with James Ramsey) of the Lowline, the 1.5 acre underground, day-lit space proposed for an abandoned trolley terminal under Delancey Street on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. Barasch’s spiel is undermined by a wonky PA system, but its most effective tool is the project’s seductive renderings showing the space as a high-tech grotto, its ceiling remade as swirling domes engineered with fibre-optics to provide enough daylight for trees to grow.

Then the questions from the panel begin. NY1 anchor Pat Kiernan is first: “I love the idea of green space in this area,” he says, “but I’m concerned about security.” Barasch responds that the site may be managed more like a cultural institution, less like open space. Later he tells me they “are thinking about stationing guards, or rangers, to maintain the public space and security.”

“Couldn’t you just poke holes in the ceiling?” asks Gawker’s Nick Denton. Barasch says the current plans call for two or three remote skylights at minimum, and that some of the daylighting needs may be answered with one or two “iconic entrances” from the street. No holes, though, since Delancey Street rumbles directly above the space.

Kiernan starts riffing: “Do we really want to be underground?” SHoP’s Christopher Sharples responds: “In a way this is a model for the subways, a way they could have natural light and other programs. Think of a souk, with other programs happening along the walls.”

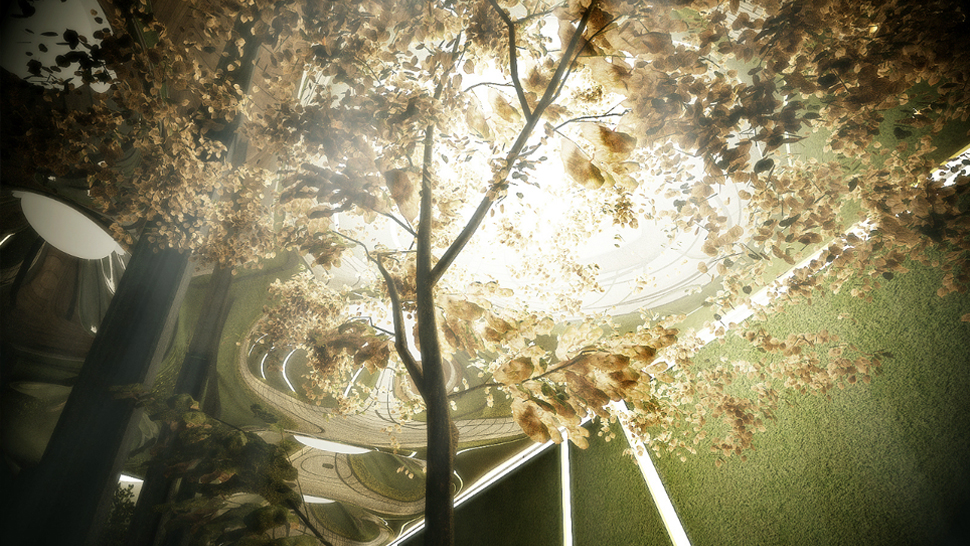

A prototype of the fibre-optic lighting technology. Image by Bit Boy.

This brief burst of questioning, which Barasch handled with modesty, made the future Lowline sound rather different from past descriptions. No more “subterranean sheep meadow or … bower in a burrow,” as Justin Davidson put it in New York Magazine in the project’s press debut. Was it to be “the world’s first underground park,” as described on Kickstarter, or a subterranean community centre? Would the trees create a grove, or be isolated like sci-fi sculpture? Would the walls be lined with shrubs or with shops? What the panel seemed to be getting at was a question I had from the start: was the Lowline even a park?

That last question, it turns out, is the easiest to answer. The Lowline, should it come to pass, is unlikely to be a capital-P park, as it is not under open sky. The co-founders, if not the media, have started to refer to it as a “culture park,” placing it on a rather presumptuous continuum between the Metropolitan Museum in Central Park and the High Line. In a letter sent on July 23, nine elected officials, including New York Senators Charles Schumer and Kirsten Gillibrand and Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver, asked the city’s Economic Development Corporation to initiate discussions with the MTA to transfer ownership of the trolley terminal to the city — a key step in making the terminal available for any new use. Which agency would take responsibility, how much it would cost to build, what will happen there, even — and this was the most important query of all — whether the MTA would turn over the space for public use, were all open questions as the Lowline made its way from the pages of New York Magazine, around the world of design blogs, and through a successful spring 2012 Kickstarter campaign (the $US155,000 raised was, until Plus Pool‘s $US273, 114 success earlier this year, the largest sum for an urban design project). What many who donated and visited the project’s subsequent exhibition at the Essex Street Market didn’t seem to realise was that the Lowline was a decade, at least one mayor, and tens of millions of dollars, away. “A major men’s magazine wanted to do a photo shoot down there in a few weeks time,” says Barasch. “It’s amazing how many people think it is all done.”

I wrote about the Lowline in 2012 as an example of the limits of Kickstarter urbanism: on Kickstarter, donors are attracted by technological gizmos, often unaware of the offline nitty-gritty of advocacy, politicking and fundraising required to actually make urbanism happen. “Pop-up” is a metaphor, after all. But as its founders have persevered, and even prospered, raising $US600,000 offline last year before they even had permission to build on the site, the Lowline has become a test case. Its founders and backers see it as a potential worldwide model, doing for underground sites what the High Line did for rail corridors: inspiring imitators like Pop Down, a mushroom-theme version proposed for London. But, like Plus Pool, it’s also a model of how Kickstarter urbanism really works.

A rendering shows the proposed location of Plus Pool, a Kickstarter-funded public pool.

Largely unseen and offline the Lowline’s founders have been doing the work urban advocates have always done, moving up the food chain of elected officials and agency heads (MTA leadership has changed multiple times since they started the project). They had to create a board. They had to fund a feasibility study to predict how much the project might actually cost to build (an estimated $US55 million, more than the New Museum). They had to meet with the community board, elected officials, parks advocates, donors, foundations. These activities are what Bryan Boyer and Dan Hill, creators of an alternate urban crowdfunding platform called Brickstarter, have called “dark matter,” the unpublicisable processes crowdfunding platforms are still figuring out how to accommodate. At the moment Kickstarter ends up being publicity for public design, a test of enthusiasm. As the Lowline founders said in their pitch, “It’s now our job to prove that the idea could work and would be popular.”

The second — popularity — happened before the first — feasibility. The same was true for the High Line, where Joel Meyerowitz’s evocative photos suggested a future mood and helped Joshua David and Robert Hammond (now Lowline board members) make their way through their own dark matter.

The Delancey Underground, the intended site of the Lowline. Image by Parker Seybold.

Recent events, like the letter, suggest the Lowline has traction. There will also be a Lowline fundraiser in October which, Barasch hopes, “will establish a visual display of support. It is a moment to reflect on the public space legacy of the Bloomberg administration. Will this be part of the agenda for the next mayor’s term?”

What hasn’t happened yet is programming: Barasch says he and Ramsey are loath to go through the process of soliciting ideas from the community until they have a public commitment from the city as partner. He is also loath to specify how many skylights, how many trees: “Everything we’ve released so far are illustrative concepts to get people thinking about how it would look and feel.” They are committed, for reasons of economic feasibility, to a central event space, that could be a rentable event venue larger than any other on the Lower East Side. The space, which Arup engineers have said can hold up to 1500 people, will probably need to raise between two and four million dollars per year for programming, staffing and maintenance.

Imagining the Lowline, an exhibition about the project. Image by gsz.

As I read through Lowline coverage, though, I see each writer, each audience projecting their desires onto it. From the hyper-local community: active space and community space. From economic development sources, in Barasch’s telling, “We want our own High Line, something that will attract people during the day not just to get drunk at night like teenagers.” From Sharples, the Lowline as an improved version of the subway experience, an idea Barasch and Ramsey have already stared to explore with renderings of peel-up entrances. Having the “culture park” be an adjunct to the street would help make it more secure and more active, but would also seem to take it away from that initial, romantic bower. Can you have a club-by-night, yoga studio/art gallery by day? I couldn’t help imagining a rainy afternoon: Who gets to choose whether it becomes an all-weather romper room for kids and caregivers or a heads-down workspace with Wi-Fi?

Here’s where the fact that the Lowline isn’t a park but a “park” becomes problematic. Because what, after all, are donors large and small giving to? Similar questions have been asked about Plus Pool, but at least we know it is a place to swim. Many of the after-the-fact complaints about the High Line come from unrealised expectations of “park:” little lawn, no playgrounds. We have some common understanding of parks, but the very elements that make the Lowline unique — the site, the remote skylights, the adjacent subway — make it a blank canvas. A mock-up can convince me that plants can grown underground, but that sci-fi moment only seems to buy one visit (Rain Room, anyone?).

Ultimately, it is the far more mundane choices about space planning and franchisees — coffee or liquor, quiet time or movie night, one tree or a grove — that will keep people coming back and make the Lowline the economic generator it needs to be to justify the capital cost. Some people think the Lowline already exists. In fact, it is only starting to be.