Your bank and credit card companies have quite a file on you. They know how often you go out to eat, how often you drink, how often you fill up your fuel tank, along with the time and location of all these activities. Cash is all but dead, and with that comes a digital trail of all your purchases watched over by private companies who don’t exactly have the best security record. But we can’t say nobody warned us.

In 1968, Paul Armer of the RAND Corporation testified in front of a U.S. Senate subcommittee about his concerns for privacy in the future. Specifically, Armer was concerned with the computerized ability to look into the lives of Americans as we entered an age where people no longer used cold hard cash.

Back in 1968 the US was far from a cashless society, so Armer tried to paint a picture of what that world might look like:

Literally, it means a society without cash or checks. In this extreme, all financial transactions, even the purchase of a newspaper, the tipping of a doorman or passing through a highway toll station, would take place via some mechanism not involving a check or cash.

The doorman’s tips may still be that rare case when cash reigns supreme, but with newspaper boxes now taking credit cards and electronic highway toll systems now the norm, this future has certainly arrived.

Armer outlined three major reasons that the computer would destroy privacy in coming years:

The first is that computer technology is introducing order-of-magnitude reductions in the cost of collecting, transmitting, and processing information. Second, centralization of data is usually a concomitant of computer use. The payoff to successful snooping is much greater when all the facts are stored in one place. Though most of the data to complete a dossier on every citizen already exists in the hands of the government today, it is normally so dispersed that the cost of collecting it and assembling it would be very high. The third factor is that computer systems with remote terminals can permit, unless proper safeguards are provided, remote browsing through the data with a great deal of anonymity.

Armer went into how a rather detailed profile of a person could be made from what we today call metadata. He explained that simply stripping the name from a set of computerized data did little to protect privacy.

I would also like to make a brief comment on the notion advanced in the United Planning Organization’s Data Bank proposal that security results from the fact that names are not included in the file. I think this is more apparent than real. This first came to me a number of years ago. I needed some data on salaries in the computer field, but none existed. So I decided to take a survey. I was concerned about the privacy aspects and set up an elaborate system whereby the respondent companies keypunched information into cards without names. They sent this information to a public accounting firm that batched the cards and sent them to me. I did not see any postmarks. We had asked for very little information other than the individual’s salary, when and in what field he had received his degree, and in which of three geographical regions he worked.

When I received the cards from the public accounting firm, the first thing I did was sort them inversely on salary (that is, highest salary first) . When I picked up the top 10 cards, I immediately knew, from the data therein, the name of each individual.

Armer flatly said that he was disturbed about the potential for violations of privacy in this computerized future. During his testimony he called for the creation of an organisation in the executive branch that dealt solely with protecting Americans’ privacy.

One of the aspects of the privacy problem that disturbs me a great deal is the fact that privacy lacks an organised constituency. In general, we find only a few Congressmen and Senators, plus a few isolated scholars and writers, and the ACLU pleading the cause of privacy. Most of their presentations tend to be philosophical in nature, as this one is, rather than in-depth studies.

Later, he continued:

It seems high time to me that some organisation in the executive branch of the government be charged with concern over the problem of privacy — just as the Department of defence is charged with providing for the common defence, and as HEW is charged with the problems of health and education.

Given the executive branch’s continued defence of their domestic surveillance programs, I’m not going to be holding my breath for a Department of Privacy any time soon.

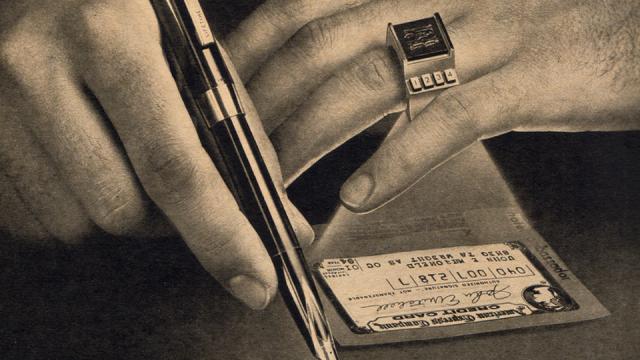

Image: A credit card ring of the future from 1964