When Steve Jobs presented the initial design for his donut-like headquarters to the Cupertino City Council, in 2011, he described the building as a reaction against suburban office parks. “We’ve come up with a design that puts 12,000 people in one building; which sounds a bit odd,” he said. “But we’ve seen these office parks with a lot of buildings, and they get pretty boring pretty fast. We’d like to do something better.” The question, though, is better for whom?

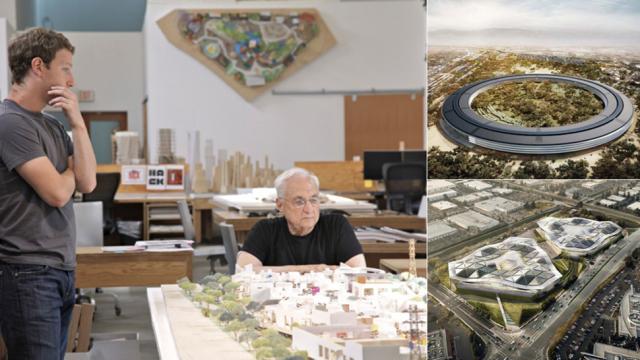

It’s hard to argue with Jobs’ logic. And very few people did — despite some grumblings about traffic, bike lanes, and free Wi-Fi, Apple’s new Foster and Partners’-designed headquarters was met with approval from the surrounding community. But from an urban perspective, the plan isn’t all that different than those office parks Jobs claimed to avoid. The $US3 billion building will be segregated from the community around it by wide swathes of greenery and parking. The only evidence of Apple the neighbourhood is likely to see? The traffic. “It is not Apple’s job to be the place-maker for Silicon Valley,” said critic Lydia Lee in an op-ed. “But for such a potent champion of good design, it’s disappointing that it couldn’t set its sights a little higher.”

And Apple isn’t alone. Nvidia, the GPU manufacturing giant, is also planning a new headquarters. Designed by Gensler, the building pulls its central metaphor from the objects it manufactures. “Taking a cue from chip design, where the connections for information flow are designed first, the design of each of the two floor plates is centered around how people move,” explained architect Hao Ko, “maximising the opportunities to connect and enhance collaboration.” The idea is to increase spontaneous run-ins between workers — but on the outside, the building turns away from its neighbours, shielded from the surrounding streetscape by a thin, faceted hillocks. Meanwhile, the design for Amazon’s newly released Seattle headquarters would quarantine workers inside of a real-world Biodome; though as an urban proposal, the plan makes solid concessions to street-level public amenities.

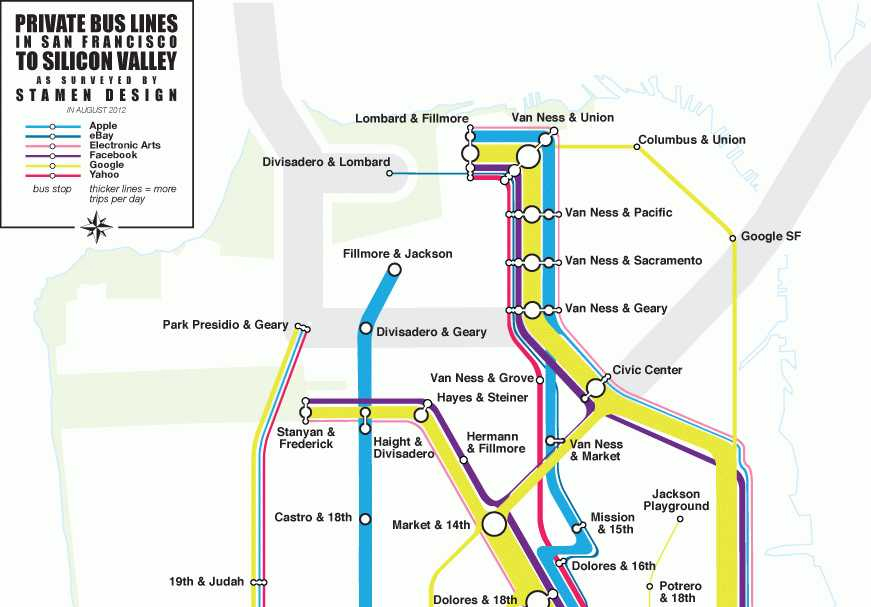

The isolationist bent has articulated itself in other ways, too — most notably, maybe, through the private bus system that has sprung up between San Francisco and Silicon Valley. The service has boomed, with companies like Google chartering busses bringing workers to and from their homes in quiet, air-conditioned, Wi-Fi-enabled style. The system is so pervasive, in fact, that it’s beginning to change the urban fabric of the neighborhoods it stops in: real estate prices near stops are skyrocketing, and hot new restaurants are clustering around them, as well. A strict segregation between public and private transit is emerging.

Why is all of this a problem? Alexandra Lange, the Design Observer Editor whose short book, The Dot-Com City: Silicon Valley Urbanism, deals with architecture in the tech world, explains that these changes are affecting the community in ways you might not expect. “With these headquarters, it’s easy to say ‘who are they harming? They’re a paradise for workers,’” she told me recently. “But we see the effects when it connects back to the people living in San Francisco. You have a private bus where you can get work done, and then you go to your private office park, and we see that it has a trickle down effect in the larger urban form. And that’s when it starts to be really problematic, and kind of undemocratic.”

Silicon Valley grew out of the promise of neoliberal San Francisco in the 1970s — and it still bears that fingerprint in its corporate sloganeering, which is full of metaphors about connecting people and creating a better physical world through digital technology. But when it comes to participation in the urban milieu, most tech companies maintain their distance. To borrow a phrase from the seminal 1995 essay, The Californian Ideology, this paradox emerged from the collision of “the free-wheeling spirit of the hippies and the entrepreneurial zeal of the yuppies.” In a recent New Yorker article about the history of social innovation in Silicon Valley, George Packer summed it up thusly:

The technology industry, by sequestering itself from the community it inhabits, has transformed the Bay Area without being changed by it — in a sense, without getting its hands dirty… Technology can be an answer to incompetence and inefficiency. But it has little to say about larger issues of justice and fairness, unless you think that political problems are bugs that can be fixed by engineering rather than fundamental conflicts of interest and value.

On the one hand, companies are interested in using architecture to promote social interaction and community amongst their employees. On the other hand, they’re not as interested in courting interaction between their employees and the communities around them.

The tech world in New York is developing in parallel to its big brother, most notably with a massive tech “campus” in one of the most isolated parts of the city: Roosevelt Island, a thin strip of land in the middle of the East River, accessible only by car or aerial gondola. There, the city is partnering with Cornell University to build a 2.1 million square foot community where students and tech workers can live and work. It is poised to become, as some call it, our own Silicon Island. “That way of thinking about the city, that these are the parts of the city that count, that these are the parts where creativity is happening, that you can map it, and make it the equivalent of a bus line,” says Lange, “is really disturbing.”

Historically, the process of segregating urban space using transit or architecture has taken place for socioeconomic reasons. In this case, it’s being done because of the popular notion that fostering “innovation” amongst brilliant young minds is a matter of choreographing the perfect, close-loop work environment. This is a pervasive concept in America, and has been since the 1950s. Brilliant work, the thinking goes, happens in spaces that encourage familiarity and interaction between employees.

Ironically, though, that isn’t always the case. One of the most storied contradictory tales comes from Building 20, the temporary wooden craphole — for lack of a better word — that MIT built during World War II. The building ended up housing all of MIT’s misfit programs later on, and it was so poorly designed that researchers from different departments were constantly forced to interact with each other. Building 20 ended up producing some of the most important work of the post-War era — and not because it sequestered its inhabitants in sterile campuses. Rather, it forced them to adapt to the conditions at hand — and to each other — the same way cities do. New York City is Building 20, at the urban scale. It shouldn’t need to build an island to house its tech community.

The counterpoint to the broader urban strategy of building isolated “campuses?” Building new offices right in the urban fabric, like Facebook is doing here in New York. On June 3rd, we learned that the company is planning to install its NYC engineering team in a new two-floor Cooper Square office, designed by Frank Gehry — the architect of their planned Menlo Park building. “It will share many of the features of our headquarters, but will be distinctly Big Apple in design and speak to the unique experience of working in a place like Manhattan,” said site director Serkan Piantino. For example, access to the culture and community in lower Manhattan, and perks like gym memberships that will keep employees engaged around the office after work. It seems simple — and it is — but companies like Facebook have the power to bring incredible economic and cultural activity to a neighbourhood. For example, dozens of companies like MakerBot and Etsy are anchoring the so-called Tech Triangle in downtown Brooklyn — bring thousands of jobs and billions of dollars in economic growth to the area.

On the left coast, a number of communities are doing the same thing — choosing to stay in San Francisco, rather than building stand-alone offices. For example, Spotify recently announced plans to expand into an office in the Warfield Building, which houses the famed music venue, in Central Market. Twitter and Zendesk, too, have chosen to invest in San Francisco proper.

Yet the benefits of keeping your employees within a closed circuit environment are clear — so it’s unlikely that we’ll see companies abandon the strategy altogether. And while it’s tempting to characterise this as a new phase in the life of American cities, in reality, the interest of companies have always driven new growth. Except these days, companies aren’t just constructing buildings — they’re acting as designers, planners and policy-makers of entire neighborhoods too.