Back in 1985, Larry Hunter was a grad student studying artificial intelligence at Yale. He had access to the kinds of computers and networking tools that few Americans even knew existed at the time. And for that reason, he saw into the future. Specifically, the future of online privacy. So how did his predictions hold up, and what does he think of this awful PRISM mess?

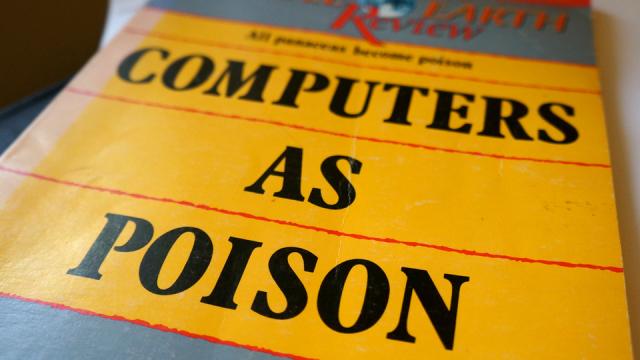

Hunter wrote an article outlining his predictions for this brave new interwebbed world of privacy for the first issue of the Whole Earth Review. He warned that it wouldn’t require much for the thin line dividing the public and private sphere to become erased in the age of digital sharing and corporate data collection.

Today, Dr. Hunter is a professor at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. I emailed him to ask about the article he wrote nearly three decades ago and what he thinks of the current state of online privacy, especially given the latest news about the NSA’s PRISM program.

You can read my take on Dr Hunter’s article over at Paleofuture’s old home at Smithsonian.

What’s your initial reaction to reading this article? Have you thought about it much since you wrote it in 1985?

I wasn’t quite as glowing about my prognostications as you were, but I am proud of the analysis. By the way, one of the reasons I have thought about it in the intervening years was that it was included in the Borzoi College Reader essay collection, right next to a piece by E. M. Forster, one of my writer-heroes. It’s also my most republished piece, having ended up in a couple of other collections as well.

How well do you think your vision on the future has held up?

I hadn’t really looked at it from that perspective, but as you point out, pretty well. I was mostly disappointed that the “personal information as property” idea didn’t pan out. I worked with James Rule for a while trying to realise that (see, e.g. this or this and chapter 8 of Grant & Bennett’s Visions of Privacy book). Jim even managed to get a state legislator (in Michigan, I think) interested in the idea, but it never went anywhere.

What do you think was your most accurate prediction for the future of privacy? What was the least accurate element?

Least accurate element: no one uses the term “bloc modeling” anymore. It does have a pretty reasonable description of what we now call social network analysis, though, even if I got the name wrong.

Do you use services like Facebook or Gmail today? How do you feel about these services?

I’m very cautious about having stuff in the cloud. I do have a Google account, but I don’t use it for my primary forms of communication. Google Docs and Drive are handy for some purposes, but I prefer to have control over my own data/documents/email, etc. I don’t do Facebook. Partly because I don’t have time, and partly because I don’t like giving advertisers access to my eyeballs. I also don’t watch much TV for similar reasons. Technology can be useful in protecting one’s self from advertisers and certain sorts of surveillance. I use an ad blocker in my web browser, and should I want to look at anything I think might send a signal I don’t want to send, I use TOR, and I have a fairly widespread PGP public key for anyone who wants encrypted communication.

Just keeping stuff on my own machines isn’t always protective. The University I work for released an email I sent to a friend as part of its disclosures regarding the Aurora shooting last year.

Do you still feel the same way about “information as property”?

Well, as you put it, it sounds a bit quaint now. I think we’ve probably lost that battle, now that there are powerful forces that rely on the value of that information for their business.

What are your concerns for privacy looking into the future?

Well, people have shown pretty conclusively the idea of privacy that I grew up with isn’t important to them. I do think that the reason personal privacy is important is that having control of who knows what about you is essential to forming human relationships. I hope that the world we end up in doesn’t undermine our ability to make choices about who to trust.

These days, I actually spend a lot of time talking about how privacy protections, particularly in biomedicine, have costs. What is lost in privacy protection regimes is openness, which often has value, too.

Does the latest news about digital surveillance by the government through the NSA’s PRISM program surprise you at all? Would it have surprised you in 1985?

Not at all. In the 1980s when I was writing the article, I was also aghast at government surveillance. I recall walking around the Yale law school and asking faculty if they knew America had a secret court (FISA was passed in 1978). No one did. Bamford’s Puzzle Palace, unmasking the NSA was published in 1982. The PRISM of its day, the Echelon program was revealed in 1988. The only thing that has changed since then was the outrage expressed by journalists, politicians and the public about these revelations has all but disappeared. There’s a wonderful line from Senator Frank Church in the 1970s: “Th[e National Security Agency’s] capability at any time could be turned around on the American people, and no American would have any privacy left, such is the capability to monitor everything: telephone conversations, telegrams, it doesn’t matter. There would be no place to hide. [If a dictator ever took over, the N.S.A.] could enable it to impose total tyranny, and there would be no way to fight back.”

What do you think must be done to protect private information in the future?

It’s possible for a dedicated and extremely careful individual to use technical means to protect his or her privacy, but probably not from governments. But for real social change to happen, large groups of people would have to rekindle their outrage at these invasions. I don’t think that’s going to happen.