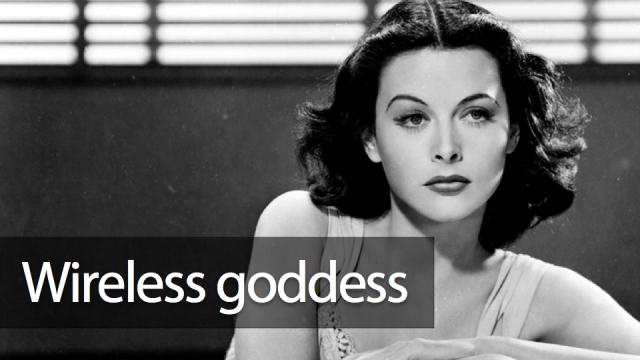

“HEDY LAMARR, screen actress, was revealed today in a new role, that of an inventor,” reported the New York Times on October 1, 1941. “So vital is her discovery to national defence that government officials will not allow publication of its details.”

The invention was not her first. Lamarr previously experimented with cola-flavoured bouillon cubes for homemade soft drinks. But her new idea, which officials would only say was “related to remote control of apparatus employed in warfare”, would become a signal innovation of the century, the technology now underlying mobile phones and Wi-Fi. Expertly explaining the genesis and consequences of Lamarr’s invention, in Hedy’s Folly, Richard Rhodes transforms a surprising historical anecdote into a fascinating story about the unpredictable development of novel technologies.

When Lamarr turned her attention to national defence, following the tragic sinking of a ship full of refugees by a German U-boat in 1940, she knew far more about armaments than most movie stars. Before arriving in Hollywood, she had been married to the Austrian munitions manufacturer Fritz Mandl, who supplied the Axis powers. Dining with Nazi generals, Lamarr not only learned about the latest submarines and missiles but also the problems with them: notably the challenge of guiding a torpedo by radio, and shielding the signal from enemy interference.

Her insight was that you could protect wireless communication from jamming by varying the frequency at which radio signals were transmitted: if the channel was switched unpredictably, the enemy wouldn’t know which bands to block. But her ingenious “frequency-hopping” idea was just a hunch until Lamarr met fellow amateur inventor George Antheil at a Hollywood dinner.

Notorious in the music world for avant-garde compositions featuring aeroplane propellers and synchronised player pianos, prior to the war, Antheil had galvanised Paris and incited riots with his cacophonous Ballet Mécanique. He had also attempted to invent an open-top pianola with which to teach basic keyboard technique. It flopped, but this background came in handy. To realise Lamarr’s idea, Antheil proposed coordinating transmitter and receiver by controlling the switching between channels with two identical piano rolls running at the same speed.

At least that was the analogy — and the analogy was what sunk their plan. When the US navy rejected their invention, Antheil remarked: “My God! I can see [them] saying, ‘We can’t put a player piano into a torpedo!’” The usefulness of their idea went unrecognised until the 1950s, and unimplemented until the ’60s.

By then the operating premise, known as spread-spectrum, had applications far beyond torpedoes and frequency-jamming. Information theory proved that a signal was made more robust — and could be transmitted more efficiently — if spread across multiple frequencies. The problems introduced by new technologies gave an old idea new salience. Today, for example, frequency-hopping prevents mobile phone conversations from criss-crossing.

The Lamarr-Antheil saga reveals much about the nature of innovation. As Rhodes rightly points out, inventions are “by definition genuinely new”, but because they are grounded in practicality, are “different from fine art or scientific discovery”. His careful historical reconstruction reveals how the pathways of innovation are intertwined, like an ecosystem.

Ideas suggested by practical needs often fail to meet those needs for trifling reasons, only to later serve purposes that could never have been anticipated.

Rhodes misses an opportunity to pursue these concepts beyond the narrow confines of this story, yet as with the invention he describes, this insightful book has more implications than he ever could intend.

New Scientist reports, explores and interprets the results of human endeavour set in the context of society and culture, providing comprehensive coverage of science and technology news.