Every time I receive a call, my mobile carrier takes note of the incoming telephone number, the time, date and duration of the conversation, and – because the call is sent through a network of mobile towers – my location. As it turns out, I’m also carrying the right kind of smart phone, which means my device itself jots down my spot on the earth, as well.

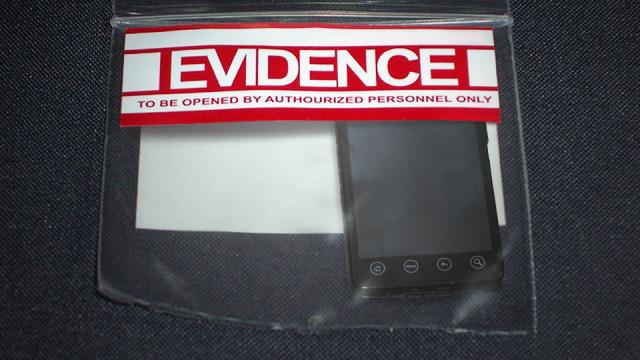

Between the brick and carrier, I’ve amassed a strikingly detailed digital portrait of every chat, check in, text and voice message I’ve received and sent. And since the diary of events is not in my possession, it’s possible that others could get access. We started wondering: What do the cops need to do to get their hands on cell phone records?

In order to convince AT&T, Verizon or whoever to cough up someone’s mobile phone tracks, cops need to present something approved by a judge. Basic account information like name, address and credit card can be obtained with a subpoena. Anything beyond that, and the judge approved thing comes in two standard forms: a court order or a warrant. To get an order, law enforcement needs to prove that a certain record is relevant and material to an ongoing investigation. Getting a warrant, on the other hand, requires probable cause. The latter needs more proof that the data is worth getting (read: harder for the cops) than the former. Simple, right?

But here’s where it gets tricky, says the Santa Clara Law Review: “As one court has appropriately observed, “the recently minted standard of electronic communication via emails, text messages and other means opens a new frontier in Fourth Amendment [the right against unreasonable searches and seizures]jurisprudence that has been little explored”. You see what that is? It’s a shoulder shrug – a we have no idea where all this new stuff stands. So on a state level, the courts don’t always agree what a judge should approve for a certain piece of information. Real-time location tracking of a mobile phone by law enforcement, for instance, has courts split. “Some say that the government needs a warrant and probable cause to track this kind of information,” explains Catherine Crump, an attorney at the ACLU, “others have held that they need to meet the lower relevant and material standard”.

On top of that, not all cell phone data is created equal. Text messages newer than 180 days? Probable cause and a warrant. Text messages older than 180 days? Relevant and material for an order. What’s the difference, you ask? Well, this new fangled mobile phone business doesn’t come bundled with an updated set of standards, so the government has been forcing 21st century technologies into a decades-old framework. The Electronic Communications Privacy Act of 1986 – the year of IBM’s first laptop computer – is one of these. Long long ago, checking your email meant that you had to download it. Leaving your email with a provider of a “remote computing service”, for, say, 180 days, implied that you didn’t want it. But that was then. Now we leave years of email in the cloud. (Thanks, Gmail, for the 7575.950349 megabytes of free storage – and counting – by the way.) Text messages – presumably because they’re also messages with text – have been lumped in the same category. The government can obtain anything older than six months by proving that it’s relevant. “Even if these rules once made sense, they are woefully outdated today,” says Crump.

Let’s break it down: Typically, outgoing and incoming telephone numbers, email and texts over 180 days old, and historical location records can be obtained with a court order. Precise real-time cell tracking, email or text messages sent within the last six months, and the physical search and seizure of a phone some courts have held require a warrant and probable cause.

Which brings us around to the detailed location history that the iPhone keeps of its user. Because that data is stored on the phone and on the computers that the phone is synched to, cops would have to physically search your phone and computer. That type of thing requires probable cause, which is tough. Law enforcement would be better off just getting a court order for historical location records. The records kept by your cell service provider seem to raise much bigger issues about privacy.

But for now, keeping our digital footprint safe just means avoiding phone calls we might later regret.