The dark, rocky face of the Dois Irmãos Mountain rises over the rainforest and through the clouds, overlooking the largest slum in Latin America. A young man emerges from around the corner of an alleyway to meet me with a handgun tucked under his arm; the local gang’s “manager.” Weaving our way down the hill through the narrow, crudely-paved cement alleys, graffiti strewn everywhere spells the letters CV”Comando Vermelho or Red Command“the drug cartel lording over this area.

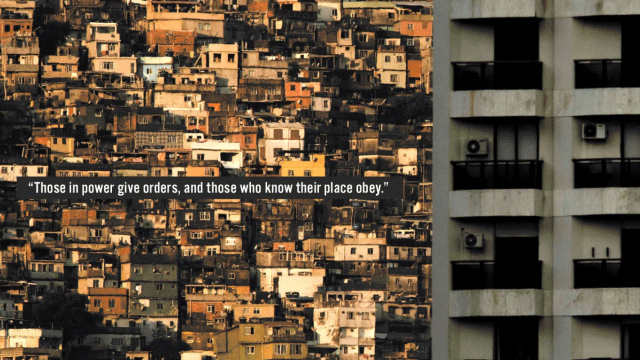

There are around 1,000 favelas”informal communities”in Rio de Janeiro, and Rocinha is the biggest. Those who live here can’t afford to live somewhere else. While the rich moved in next to the beach, the poor had to climb a hill (the word “hill” is synonymous with “slum” in Rio). These communities are home to members of the working class”maids, cleaners, and trinket-sellers among others. Lying between two of the richest neighbourhoods in the city, Gávea and São Conrado, Rocinha (whose name means “little farm”) was founded in the 1920s when a few farmers from Northeast Brazil set up shop on patch of land next to Dois Irmãos, selling their produce to locals.

The manager walked me up to one of the “smoke shops,” which is really just a couple of kids and a backpack cornucopia of mind-bending substances including weed, coke, and ecstasy. People were constantly coming up and buying in a non-stop flow of customers, and the boys had to record every single purchase (if not, it’s coming out of their pocket). These kids, no more than 16 or 17-years-old, are the front line: They’re the first getting shot when cops storm the favela. But the boys aren’t afraid.

“When the police come, we shoot off some fireworks, then we hit the battle stations,” the older one said. “We’ve got three hundred machine guns and a 50-calibre rifle. It can shoot down helicopters.”

“But we don’t wanna use that one because there are houses nearby,” he added quickly.

The story here isn’t just one of crime, drugs, and urban warfare, though. It’s also a tale about climate refugees, and what happens when they are ignored. Migrants have come to these favelas in the past due to weather shocks in other parts of Brazil. But now an era of climate change could send more people streaming to Rio and other Brazilian cities. And in a dark twist, the Brazilian government under far-right President Bolsonaro could end up worsening these twin crises by letting the Amazon burn and cracking down on the people in favelas with nowhere else to go.

“I came here more than 30 years ago, wanting to make something of myself,” Gloria da Silva, a resident, told me as we sat in the back of her chicken shop later that day.

“I guess you could say I had big city dreams!” she laughed. “Back then, this area still used to have a few wooden shacks; not these concrete buildings you see today. When I arrived, I first went to stay with my uncle, then worked as a housekeeper for a rich white family until I saved enough money to get my own place. I’ve had my shop around six years now and both my sons work here. I’m proud they didn’t get mixed up in drugs and gangs.”

Like many people here, da Silva came from Ceará in Brazil’s Northeast. The region was once a prosperous part of the Portuguese Empire, with many colonial plantations and the heart of the slave trade (slavery itself wasn’t abolished in Brazil till 1888, making it the last country in the Western world to do so and way after independence from Portugal).

“This was a situation that was very common in the 19th century,” Jose A. Marengo, General Coordinator of Research and Development at the National Centre for Natural Disaster Monitoring and Alerts (CEMADEN), told me. “During the 1877-78 drought, almost 500,000 people died from diseases like malaria after migrating to the city of Fortaleza, where the mayor built refugee camps so they wouldn’t come into the city, and disease spread.”

Now, it’s a dry, arid semi-savannah known for droughts and occasionally, flash floods. But many of the great migrations coincided with a dry spell. In another dry spell in 1915, 100,000 people died and another 250,000 were forced to leave their homes. Yet another series of devastating droughts hit the area in the 1950s, triggering a mass exodus. Others followed in the 1970s and early 1980s. Droughts and flooding made it harder for farmers to earn a living, so they moved south to São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. The dry conditions were often aggravated by greedy local elites, who skimmed off federal relief funds and built water reservoirs on private land, as well as a lack of readiness by the nordestinos themselves.

“My family used to work on the land, but they didn’t own the land they farmed, and each year it was getting harder and harder,” said da Silva. “After the 1987 drought, it got [to be] too much.”

“Droughts are recurrent there but the population is notably underprepared,” explained Marengo. “We are talking about people that live in the semiarid region, poor farmers, non-educated and with a very low level of human development. They are very vulnerable in the present.”

The new arrivals weren’t entirely unwelcome when they arrived in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. Since the 1930s, the government encouraged nordestinos to move south as a source of cheap labour.

“Around 80 per cent of people I know here are from the Northeast”most people in the favelas in Rio come from the Northeast,” Evandro Pipoka, a popular local tattoo artist and second-generation carioca (Rio native) whose mother came from Ceará in the 1960s, told Gizmodo. “There’s more people from the Northeast than from here. And there’s more of us doing business, too. Cariocas have a reputation for being lazy because they’re next to the beach, but we work hard. Most businesses want to hire us because cariocas are lazy.”

But since the economic downturn in the 1980s and through to today, it quickly became apparent that the metropolitan centres in the south were simply not prepared to deal with this influx. Many migrants struggled to find decent housing, clean water or even a place to sleep.

The favelas had other problems, too. They were squats, which means they weren’t recognised by city planners for decades. To this day, many of them don’t appear on Google Maps. As unofficial settlements, they’ve long been deprived of running water, electricity, and basic services. Because of their lack of means and education, some southerners saw these new immigrants as criminal hicks. Since no one seemed to care what happened there, that allowed a new power to move in.

Rocinha actually contains two favelas. The side closer to the metro is lively, bustling, and open to tourists. Armed police patrols roll past in black flak jackets and automatic rifles. But there’s another side, a hood-within-the-hood where gringos don’t go. Here, 20-year-olds in tank tops, flip-flops, and baseball caps walk around bearing military-grade assault weapons inscribed with the nickname of their boss.

This part of favela has a reputation as a lawless no-go zone. Police only go there in numbers to conduct raids. Instead, powerful narco-trafficking gangs like CV and their rivals maintain their own brand of law-and-order.

“We have a saying in Brazil: manda quem pode e obedece quem tem juizo,” one of the gang members told Gizmodo, a phrase that translates to “those in power give orders, and those who know their place obey.”

But the order that’s been established could be upset. Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, and his ally, Rio Governor Wilson Witzel, have vowed to crush the favela gangs.

“A policeman who doesn’t kill, isn’t a policeman,” Bolsonaro once said. Comparing the city’s drug dealers to Palestinian militant group Hamas, Witzel told his officers to shoot on sight and rain down bullets from helicopters.

Cops appear to have taken this advice to heart, shooting dead 1,810 people last year in Rio alone, a rate of five a day and the highest since records began. The favelas’ narcos are ready for war, but that often means that favela dwellers are caught in the fray.

Da Silva is proud her sons stayed away from drugs and gangs but shies away from saying much on the subject. Given the gang’s military-like control of the neighbourhood, the ruthless way they deal with squealers, and that it’s the first time she’s seen me, that’s completely understandable. Pipoka, the tattoo artist, was more forthcoming.

“The drug dealers don’t need to shoot, but police need to respect the rights of citizens in the favela,” he said. “The media always talks about criminals in the favela, but we’ve also got too many corrupt police.”

During one raid on Rocinha earlier this year, an innocent taxi driver, 27-year-old Joselino Soares da Silva, was killed in a shootout between gangsters and police. His fellow cabbies responded by blockading the freeway out of Rocinha with their vehicles. Elsewhere in the city, the death of 8-year-old Ãgatha Félix, shot in the back during a raid on another favela, Complexo do Alemão, drew hundreds out in protest.

“For us it’s normal; I trust these guys more than the police, and it’s like that for most of the community,” my local go-between told me as we walked past a couple of gun-packing teenagers. “These guys are from here, so I see them every day. If I talk to the police, I don’t know what might happen.”

Caught between drug dealers and the police, residents are liable to catch a bullet from both sides. But there are other ways the Bolsonaro regime is making matters even more volatile.

While unleashing a wave of violence in the favelas, Bolsonaro and friends have also turned up the heat in another part of the country. Droughts have been recorded in the Northeast since 1583, and many natural causes such as El Niño are to blame, recent years have seen more severe water scarcity experts have pinned on another culprit: global warming.

Under Bolsonaro, intentionally set fires have raged across the Amazon rainforest, one of the world’s last true remaining wildernesses. According to satellite data the number of fires has surged 84 per cent since last year, turning green jungle into a scorched, barren wasteland. It was one the biggest year-to-year jumps in area deforested on record.

Bolsonaro blamed NGOs then, bizarrely, Leonardo DiCaprio for starting the inferno, which is kind of like blaming doctors for diabetes. Backed by the agribusiness lobby, Bolsonaro’s opened up the rainforest for “development,” letting ranchers and their armed thugs grab land from indigenous people and burn it down for their cattle.

The rainforest is an important carbon sink, meaning it absorbs carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. But cutting or burning it down releases all that carbon back in the air like a flatulent grandpa, pushing us closer to ecological meltdown. If enough of the rainforest is destroyed, what remains will reach a tipping point from which there’s no coming back. The Amazon will tip into a new state that looks more like Northeast Brazil’s dryland savannah than the jungle it is now. That could beget a series of feedback loops in the Northeast as a result.

“We can expect more extreme conditions,” Marengo explained of the rainforest’s destruction. “The impact will be indirect, but certainly important: drier conditions in Northeast Brazil, and a more arid climate in the region, with longer dry spells and a water crisis situation. Right now, while the recent governments have helped the local farmers with getting credit and measures like medical care and water trucks, if that help ends we may have a migration situation from the poor rural area into the cities in Northeast Brazil, or to other states, such as São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro.”

Putting it another way, more droughts means more migrants. Of course, stoking fears about them is Xenophobia 101. Arrivals coming from the Northeast aren’t why Rio has a crime problem”decades of poverty, neglect, racism, corruption and drug laws are”but it’s not unreasonable to ask how a city already dealing with these issues will handle more climate refugees pouring into the CV side of town.

The 2012-2016 drought was the most severe in decades, affecting over 33 million people, kicking off protests and forcing the government to declare a state of emergency. The Northeast is acutely vulnerable to global warming as the climate shifts from semi-arid to arid, and human activity like deforestation and clearing land for cattle grazing is literally throwing fuel on the fire. At the same time, Bolsonaro’s crackdown on his own citizens in the favelas targets the same people reeling from the climate disaster.

Climate migration is hardly a problem limited to Brazil. If trends continue, up to a billion people (mostly in the global South) will have to pack up and leave their homes by 2050 as the climate crisis worsens. It’s these people, who contribute very little to the climate crisis, who will bear the brunt of this catastrophe and the mayhem it will cause.

How the world treats those refugees will be a defining issue of the 21st century. The specter of ecofascism, a desire to shut the gate and throw away the key, is growing on the right as is a desire to disengage from the very policies and negotiations that could slow climate change. If the world continues down the road it’s on, the growing anguish in Rio is a preview of what’s to come.

Niko Vorobyov is a government-certified (convicted) drug dealer turned writer and author of the book Dopeworld, about the international drug trade. You can follow him @Lemmiwinks_III.

Editor’s Note: This article has the US release date. We will update this article as soon as possible with an Australian release date, if available.