Two decades ago, a rare but deadly fungal infection began killing animals and people in the U.S. and Canada. To this day, no one has figured out how it arrived there in the first place. Now a pair of scientists have put forth their own theory: Tsunamis, sparked by a massive earthquake in 1964, soaked the forests of the Pacific Northwest with water containing the fungus.

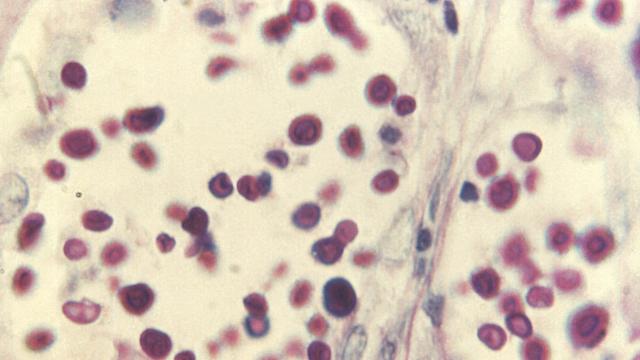

The yeast-like fungus is called Cryptococcus gattii. Like many species of fungi, it tends to prefer living in soil, particularly near trees. But its dormant airborne spores can also invade the lungs of living animals, where they start growing again; from there, they can infect the nervous system.

Most people exposed to C. gattii never become sick, and it isn’t contagious between people. But it’s one of the deadlier fungal infections in the world, capable of sickening even perfectly healthy people. In people with documented illness, its mortality rate can be as high as 33 per cent.

C.gattii has long made its home in tropical and subtropical environments, particularly around Australia and Papua New Guinea. But in 1999, outbreaks of the same unique types of C. gattii started appearing along the North American Pacific Northwest, with no clear explanation as to how the fungus got there. Since then, these subtypes have firmly established itself throughout the West Coast, as far down as California, sickening hundreds of animals and people.

There have been various theories about how C. gattii ended up in the Pacific Northwest. Some scientists, for instance, have argued that it first emerged from the rainforests of South America. Others have said it came from Australia. But as mysterious as its origin is exactly how it got from point A to point B.

The authors of this new paper, published in mBio, had previously theorised that ships from South America carried the fungus to the coastal waters off the Pacific Northwest, soon after the opening of the Panama Canal in 1914 had established relatively easy transportation between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans.

That timing would make sense, with genetic evidence suggesting that all the populations of C. gattii in the U.S. and Canada are somewhere between 66 and 88 years old (fungi usually clone themselves to reproduce, making it easier to track their evolutionary journey).

Now they’ve gone one step further, arguing that the fungus was able to sustain itself for decades in the waters of the Pacific Northwest before another major event actually spread it to the mainland: the 1964 Great Alaskan Earthquake.

Still on record as the largest earthquake ever detected in the Northern Hemisphere and the second largest worldwide — registering a 9.2 on the Richter scale — the natural disaster killed over a hundred people, destroyed buildings, and set off a chain of tsunamis that swelled into the Pacific Northwest and reached as far as Japan.

“This one event, like no other in recent history, caused a massive push of ocean water into the coastal forests of the [Pacific Northwest],” the authors wrote. “Such an event may have caused a simultaneous forest C. gattii exposure up and down the regional coasts, including those of Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada, Washington, and Oregon.”

The authors’ case is almost entirely circumstantial. But they do bring up some compelling evidence. For one, based on genetic analysis, the strains of C. gattii now present in the Pacific Northwest all seem to have arrived there in one major event decades before 1999.

Early investigations of outbreaks also found higher levels of the fungus in the trees and soils closer to sea level, which is what you’d expect to find if it had originally came from the ocean. And most tantalising is that at least one Seattle patient became sick with C. gattii in 1971, almost three decades before the 1999 outbreaks but post-tsunami.

“Perhaps most importantly, we haven’t found data that would discount or disagree with the hypothesis,” lead author David Engelthaler, co-director of the Pathogen and Microbiome Division at the Translational Genomics Research Institute in Arizona, told Gizmodo via email. “Second, there is no good alternate hypothesis that fits all the data.”

Unusual as the theory is, the authors note that there are other instances of a natural disaster sparking outbreaks of rare infectious disease. For example, a 2011 tornado in Joplin, Missouri might have spread a wave of flesh-eating infections caused by the Apophysomyces fungus. Indeed, Engelthaler and his co-author argue that most major events of disease can be considered black swans, a term coined by the economist and philosopher Nassim Taleb to describe events caused by an unforeseeable mix of circumstances.

There’s still plenty more work to be done in unravelling the mystery of C. gattii. According to Engelthaler, future research could help the theory sink or swim.

“We hope to do more environmental analysis that is designed specifically to test the hypothesis — for example, do we find great presence of the fungus in the soil and trees within the known tsunami run-up region as opposed to locales that tsunami water didn’t reach,” he said. Similarly, if other coastal waters contained C. gattii, but there weren’t outbreaks in the surrounding area, that would suggest something unusual happened in the Pacific Northwest.

Even if the theory does turn out to be true, though, there’d still be the question of why it took decades for cases to start regularly showing up. And if it’s true that C. gattii can end up surviving in coastal waters for long periods of time, then we also have to figure out whether there are other areas of the world that could be at risk for their own outbreaks. To that end, Engelthaler and his colleagues are surveying water samples around the world to look for traces of the fungus that might have gone unnoticed before.

In the meantime, any aspiring horror movie screenwriters out there could do a lot worse than being inspired by the potentially real-life tale of an earthquake unleashing a lung- and brain-infecting fungus upon California.