I can’t think of another show in recent times that has made me laugh harder than Netflix’s Tuca & Bertie has. But, folks…we need to talk about the birds.

The absurdist humour of Tuca & Bertie, which stars Tiffany Haddish and Ali Wong, would feel at home in an old episode of SpongeBob. As an anxious, presently-sober writer who was a one-time binge-drinking party animal, I relate heavily to its realistic representation of urban millennial living.

A lot of other people like it too for its incisive commentary, diverse cast, and writing. As someone who doesn’t watch television much, I don’t think I’m qualified to say more about the show than that.

But I am someone who watches birds a lot, so I have an interesting perspective to provide.

I go birding in my local park nearly every day and am presently doing a Brooklyn Big Year, meaning I’m trying to see as many different bird species in Brooklyn as I can (I’m hoping to break 200!).

Like nearly all bird watchers, I suffer from an illness—my brain forces me to identify the bird species depicted in any creative work of fiction or nonfiction. Tuca & Bertie was not exempt.

How do you identify a bird’s species, let alone a bird on TV? Typically, I’d first consider the habitat, time of year, and location to whittle down from 10,000 possible birds to the few dozen that I might expect to appear in a given place. Then, I’d weigh the bird’s overall appearance and behaviour to get down to the family—a bird with a conical bill in a tree is more likely a seed-eating finch, while a leggy wading bird with a skinny bill is more likely a heron or an egret.

From there, you can use the sum of the finer details of the bird’s appearance and behaviour such as the colour of its feathers and feet or how it walks to nail a specific species or group of species. Some species are hard to tell apart until they open their beak, when they make a species-specific call or song akin to a Pokémon saying its name.

Birding in Tuca & Bertie presents both advantages and disadvantages over birding in real life. And that’s despite the obvious animation hurdle. Occasionally the show will simply say the species name, making it easy to assign the identification.

Sometimes, the field marks are abstracted in a way that makes identifying the species obvious. But all of the birds live in a bird-world approximation of New York City and speak the same language, meaning you generally can’t rely on location or calls in order to nail a correct ID.

Anyway, I’m a relatively novice birder so I can’t promise these are 100 per cent accurate, though even the best birders occasionally botch a species identification. And I might just be the first person to try and identify bird species from Tuca & Bertie.

Tuca: Toco Toucan

The shape and size of Tuca’s bill would imply she’s from the Ramphastos family of typical toucans, while the coloration of her body and white mask, as well as the dark spot on her orange bill, told me she was a toco toucan. The toco toucan is the largest and perhaps most famous of the toucan species, with the longest bill relative to its body size of any bird in the world.

It lives in South America in open habitats, but you can probably see it at the local zoo. Scientists think its large bill is a tool both for controlling its body heat and for intimidating other birds.

Bertie: Song Thrush

Bertie’s brown colour and spots initially pointed me towards one of the many ground-dwelling thrushes which can be found across the world. Later, the character explicitly tells you she’s a song thrush, allowing me to pin “song thrush” as the definitive species identification. The song thrush is found throughout Europe and is pretty closely related to the American robin, another thrush.

The song thrush can be found on the ground feeding on worms or in trees eating fruits, and earned its name from its cheerful, repeating songs.

Speckle: Robin

The show itself tells us early on that Speckle is a robin. The field marks—yellow bill, red breast, and grey head—and location, the United States, would suggest that he is a female American robin. The American robin is a kind of migratory thrush, and one of the most well-known American birds.

However, at one point during the show’s first episode, the creators use a photograph of the similarly-coloured European robin to represent Speckle. The European robin is instead a kind of insect-eating bird found in Europe and Northern Africa from an unrelated bird family called the chats.

During the season’s third episode, a birdwatching character named Nicola narrates sexual encounters between Speckle and Bertie, stating that they are a “male robin and female song thrush,” further specifying that the robin is “of this region.” I settled on American robin for Speckle’s ID. The character, Nicola, is then admonished by her mother for “peeping,” and her reflection in a mirror calls her a “bloody pervert.”

At this point, I felt exposed, utterly dunked upon, and like I probably shouldn’t be spending all of this time trying to identify the birds in a cartoon. But I had already committed to writing this blog. So onward I went.

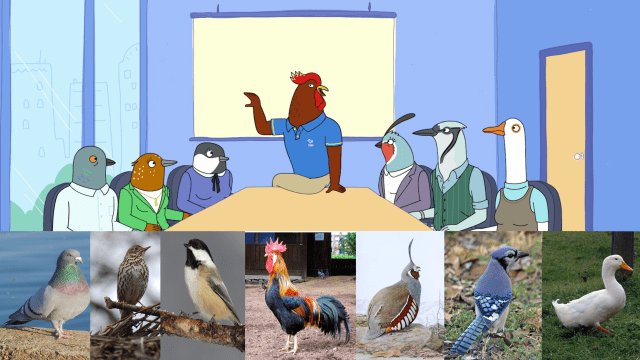

The mixed-species flock

Birds of different species with similar feeding habits might flock together to feed. In real life, this looks like a handful of songbirds travelling together and eating insects in different parts of the tree, keeping their eyes out for predators. But when birds take on anthropogenic qualities, it’s hard to predict who might appear in a mixed flock.

In Conde Nest’s case, the flock includes species that might not flock together in real life. From left to right, we see a feral pigeon (determined by the beak shape, overall colour and presumed iridescence on the neck), Bertie, and a chickadee. There are several species of North American chickadee, two of which would show a black forehead and chin.

These species look nearly the same, so they’re most reliably distinguished by their different songs and the location. Given the fact that real-life Condé Nast is located in New York, we’ll assume that in this case, we’re looking at the black-capped chickadee, rather than the Carolina chickadee which, though common in New Jersey, has never been recorded in New York City.

Moving on, we have the cocksure Dirk who is appropriately a rooster, a mountain quail (which I determined by the plumage and the shape of the frond) and Bertie’s boss Holland, a blue jay, which normally doesn’t play as nicely in the mixed flock. I think to the right of Holland is a domestic duck, descended from the ubiquitous mallard.

Ebony (and Sophie) Black: Ravens

Though ravens are a far less common sight than the closely-related, similar-looking crow in New York City, Bird Town isn’t New York, and you can’t rely on a species’ prevalence alone to nail down a proper identification. In this case, The larger bill helps determine that Ebony and Sophie Black are ravens. In real life, a raven would typically be much larger, around the size of the hawk, and would have a diamond-shaped tail versus the smaller crow’s more squared-off tail.

Pastry Pete: Penguin sp.

The manipulative baker Pastry Pete presents conflicting field marks that make me unsure of his specific species. However, his barrel-chested body and beak shape implies that he is a penguin. If I somehow ended up seeing a bird like Pastry Pete in the wild, I would mark him on my checklist as “penguin sp.,” meaning that I could only narrow down his identification to a category of animals.

There are plenty of other birds that I noticed throughout the show—Dakota with a Y is a canary, then there are pileated woodpeckers, owls (I called them long-eared owls), and a northern cardinal who’s a coworker of Speckle’s.

Identifying birds’ species in fiction is a curse thrust upon the most serious bird watchers. It is sort of fun, but mostly people hate it. One might assume the creators behind Tuca & Bertie never expected this level of dedication but then again, considering the details and variations included, perhaps there’s a bird watcher among their flock.