Doctors in London, UK have seemingly accomplished a momentous feat in HIV treatment. They claim to have used a stem cell transplant to successfully clear any traces of the virus in their HIV-positive male patient. It’s the second time such a procedure has appeared to permanently treat the lifelong infection, though the doctors caution it’s not a confirmed cure just yet.

In 2007, Timothy Ray Brown underwent a stem cell transplant to treat his leukemia. The donor stem cells would effectively replace his defunctive bone marrow, the base from which new blood cells are grown in the body (and source of his cancer). Because he was HIV-positive, his doctors decided to test out a theory that replacing his marrow with the marrow of someone naturally resistant to HIV would also flush out the virus for good, since it primarily infects and kills our white blood cells.

A year later, at a scientific conference, Brown’s doctors reported that he indeed became free of the virus without the help of antiretrovirals, and he has remained HIV-free ever since. Because Brown only chose to disclose his identity later on, he was initially simply known as the Berlin patient, the place where he received his original transplant. As it turns out, the moniker was actually given to another person living with HIV a decade before, who despite still having signs of the virus in his blood has also remained healthy without the need for antiretrovirals.

(This earlier Berlin patient, still anonymous, is thought to have had his own peculiar mutation separate from the mutation used to cure Brown).

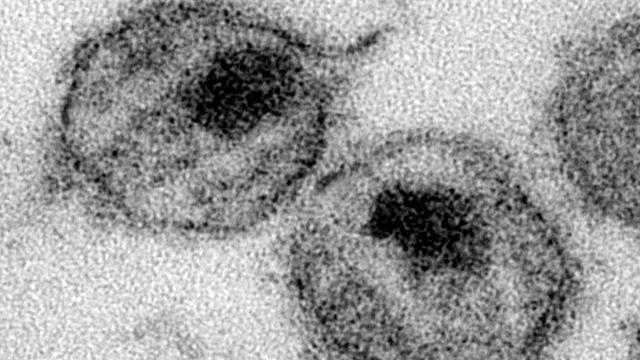

In this latest case, set to be published in Nature on Tuesday, the London patient was also given a stem cell transplant to treat an advanced form of blood cancer, Hodgkin’s lymphoma, that had spread beyond his lymph nodes. And like Brown, the patient received donor stem cells from someone with two copies of a certain mutation in the CCR5 gene, which regulates the CCR5 receptor found on white blood cells. The mutation, CCR5-delta 32, makes it impossible for some strains of the HIV virus to infect these cells, thus stopping the infection in its tracks.

According to the doctors, they were able to take a less aggressive tack with their patient this time. Rather than giving the patient both radiation and chemotherapy before the transplant, as with Brown, the London patient only had to undergo chemotherapy. Nevertheless, he still developed blood cells with the CCR5 mutation after his transplant—cells that proved resistant to infection from samples of HIV previously taken from the patient in a petri dish. More importantly, the man seems to have remained free of the virus without drugs for 18 months. At this point, though, the doctors say they will have to wait longer and run more tests before he can be declared cured.

Still, by replicating the same procedure, the doctors appeared to have confirmed that Brown’s full recovery wasn’t an aberration.

“By achieving remission in a second patient using a similar approach, we have shown that the Berlin Patient was not an anomaly, and that it really was the treatment approaches that eliminated HIV in these two people,” said lead author of the upcoming study Ravindra Gupta, one of the man’s doctors and infectious diseases physician at the University of Cambridge, in a statement.

Some researchers have speculated that Brown’s development of graft-versus-host disease — a condition where donor cells attack their host body’s cells—following his transplant might have been a factor in his cure, not just the reprogramming of his blood cells. And the same might be true of the London patient, since he also developed a relatively mild case of graft-versus-host disease. Otherwise, though, the patient has tolerated the transplant with few side-effects.

It’s unlikely stem cell transplants will ever become a widely used cure for HIV, though, no matter what ultimately happens to the London patient. Even for people with blood conditions like leukemia, the procedure is often a last resort option, since it’s incredibly risky, sometimes ineffective, and and even occasionally fatal (Brown himself needed another transplant a year later after his leukemia returned and suffered serious complications). And nowadays, most people with HIV can keep the virus in check with antiretrovirals, and with much less dramatic side-effects than a transplant would entail.

In many cases, latent levels of the virus are so low as to make it virtually undetectable (and untransmittable). The CCR5 mutation also doesn’t provide resistance to all known strains of HIV, so there are people living with HIV who couldn’t benefit at all.

That aside, it could be a worthwhile option for the select group of people living with HIV who need a transplant regardless, such that efforts could be focused on finding donors with the CCR5 mutation. It also provides more hope that future treatments based on targeting CCR5, such as gene therapy, could someday provide a more reliable and palatable cure for some living with HIV.