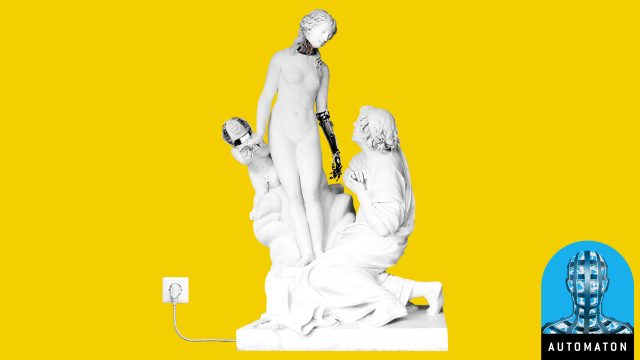

The age of android brothels and lifelike sex robots may seem cutting edge — until you’ve heard the story of the man who had sex with his ivory sculptures, and the Greeks who habitually had public intercourse with statues.

In an excerpt from her new book, Gods & Robots, a deep and lively look at how Greek and other early mythologies conceived of artificial intelligence and automation, author and historian Adrienne Mayor reveals how old the concept of the sexbot really is. — Brian Merchant

A number of Greek tales, as in other cultures’ myths, describe lifeless matter, statues, idols, ships, and stones brought alive by gods or magic.

The most familiar classical example of a statue magically enlivened by divine order is the myth of Pygmalion and his love for a nude ivory statue of his own making. Ovid’s version (Metamorphoses) is the most vividly detailed account of Pygmalion. The young sculptor is disgusted by vulgar real women, so he sculpts a virginal maiden for himself. In the modern imagination, his statue is often pictured as marble, but in the myth it is ivory, a warmer, organic medium.

His ivory maiden looks so real that Pygmalion immediately “burns with passion for her,” caressing her perfect body with awe and desire, imagining that were he to press against her forcefully she would actually bruise. He showers the statue with gifts and words of love. In the Temple of Aphrodite he beseeches the goddess to make his “simulacrum of a girl” come alive.

Pygmalion returns home and makes love again to his fantasy woman’s ivory form. To his astonishment, the statue warms to his kiss, and in his embrace her body becomes flesh. Unlike cold marble, ivory is a once living material with a soft, creamy lustre.

In antiquity, ivory figures were tinted with subtle, naturalistic colours to resemble real skin tones. Ancient audiences would have imagined her as an exquisitely sensuous, flawless female form. Under her maker’s caresses, Pygmalion’s statue awakens into consciousness and she “blushes with modesty.” Aphrodite has answered his prayer.

It is important to emphasise that Pygmalion’s artifact was not constructed to be an automaton. Its realism became reality supernaturally, thanks to the goddess of love. This oft-told ancient “romance” of artificial life takes on new relevance today because it presages ethical questions posed by modern critics of lifelike robotic dolls and AI entities specifically designed for physical sex with humans. “Is it possible,” one writer asks, “to have consensual sex with a robot, even one that’s aware of its own sexuality?”

Although the Pygmalion myth is often presented in modern times as a romantic love story, the tale is an unsettling description of one of the first female android sex partners in Western history. It is not clear 108 Chapter 6 that Pygmalion’s passive, nameless living doll possesses consciousness, a voice, or agency, despite her “blushes.” Has Aphrodite transformed the perfect female statue into a real live woman, with her own independent mind—or is she now “just a better simulation?”

The statue is described as an idealised woman, more perfect than any real female. So Pygmalion’s replica “surpasses human limits,” much like the sex replicants in the Blade Runner films that are advertised as “more human than human.” Ovid, notably, does not describe her skin and body as feeling lifelike. Instead Ovid compares her flesh to wax that becomes warm, soft, and malleable the more it is handled — in his words, her body “becomes useful by being used.”

Ovid ends his fairy tale with the marriage of Pygmalion and his nameless living statue. He even adds that they were blessed with a daughter named Paphos, a magical feat of reproduction intended to show that the ideal statue became a real, biological woman.

Notably, the plot of the film Blade Runner 2049 turns on a similar magical reproduction of a replicant, the biological birth of a baby to the replicant Rachael, which is supposed to be impossible for artificial life forms.

In retelling the Pygmalion story, Ovid was drawing on earlier narratives, now lost. One source was Philostephanus of Alexandria, who recounted a full version of the myth in his history of Cyprus, written in 222–206 BC. In a variant by the later Christian writer Arnobius, Pygmalion sculpts and makes love to a statue of the goddess Aphrodite herself. No artistic representations of the Pygmalion myth survive from antiquity.

But many medieval illustrations show Pygmalion interacting with his ivory statue; the tale served as a kind of prurient religious warning against worshipping idols. By the eighteenth century, European storytellers had finally given Pygmalion’s statue a name, Galatea (“Milk-White”). Variations on the Pygmalion myth have proliferated over millennia, inspiring myriad fairy tales, plays, stories, and other artworks.

In the Pygmalion myth, the sculptor’s ivory statue is “clearly an artifactual being created for sex.” But Pygmalion’s ivory woman was not the only statue that aroused an erotic response in viewers in antiquity. There is a long ancient history of agalmatophilia, statue lust. Lucian and Pliny the Elder told of men who were passionate for the beautiful, undraped statue of Aphrodite at Knidos. It was created by the brilliant sculptor Praxiteles in about 350 BC, the first life-size female nude statue in Greek art.

The men surreptitiously visited her shrine at night, and stains discovered on Aphrodite’s marble thighs betrayed their lust. The sage Apollonius of Tyana tried to reason with a man who fell in love with the Aphrodite statue by recounting myths of unhappy trysts between gods and mortals. In the second century AD, the Sophist Onomarchos of Andros composed a fictional letter by “The Man Who Fell in Love with a Statue,” in which the thwarted lover “curses the beloved image by wishing upon it old age.”

In yet another infamous case, reported by Athenaeus one Cleisophus of Selymbria locked himself in a temple on the island of Samos and tried to have intercourse with a voluptuous marble statue, reputedly carved by Ctesicles. Discouraged by the frigidity and resistance of the stone, Cleisophus “had sex with a small piece of meat instead” à la Portnoy.

Most “statue lust” stories feature men having sex with female statues, but several ancient sources relate the sad tale of the widow Laodamia (also known as Polydora) whose beloved husband, Protesilaus, died in the legendary Trojan War. The earliest known text was a fifth-century BC tragedy by Euripides, but the play no longer exists. Ovid’s version takes the form of a letter from Laodamia to Protesilaus.

They were newlyweds when he departed for Troy (the war lasts a decade). Laodamia aches for her husband’s return. Each night Laodamia erotically embraces a life-size waxen image of her husband, who was “made for love, not war.” The replica is so realistic that it lacks only speech to “be Protesilaus.” Hyginus recounts a variation of the tale. When Protesilaus is killed, the gods take pity on the young couple and allow Protesilaus to spend three precious hours with his wife before he must return to the Underworld forever.

Distraught with grief, Laodamia then devotes herself to a likeness—this time in painted bronze—of her husband, showering the statue with gifts and kisses. One night, a servant glimpses the young widow in passionate embrace with the male figure, so lifelike that the servant assumes it is her lover. The servant tells her father, who bursts into the room and sees the bronze statue of the dead husband. Hoping to end her torment, the father burns the statue on a pyre, but Laodamia throws herself on the pyre and dies.

One can compile about a dozen accounts of heterosexual and homosexual love for statues in Greek and Latin sources. Historian of medieval robots E. R. Truitt calls these tales and the story of Pygmalion “parables about the power of mimetic creation” and the ways one can “confuse the artificial with the natural.”

Alex Scobie, a classicist, and the clinical psychologist A.J.W. Taylor have pointed out that this particular sexual “deviance” arose at a time when Greek and Roman sculptural artistry was achieving a high degree of realism and idealised beauty. Beginning with Praxiteles, there was “an abundance of sculptured human figures with which people could identify,” life-size and very naturalistic in appearance, colouring, and poses.

Beautiful, realistically painted statues were not only plentiful but “conveniently accessible” in temples and public places, encouraging “the populace to form personal relationships with them.” Nude cult statues were often treated as though they were alive, given baths, clothing, gifts, and jewellery. Writing in 1975, Scobie and Taylor concluded that agalmatophilia for marble (or ivory or wax) statues that replicated life with intimate realism was a pathology made possible by the technical expertise of superbly talented artists in classical antiquity.

As they and art historian George Hersey, writing in 2009, speculated, advances in anatomically realistic silicone sex dolls and biomimetic, AI-endowed cyber-sexbot technologies will result in the ancient paraphilia evolving into a modern form of “robotophilia.”