Kilauea volcano has quieted down considerably since August, and recovery efforts are now in full swing. That includes a major milestone coming up on September 22, when the National Park Service (NPS) is set to re-open parts of the colossal Hawaii Volcanoes National Park, which has been closed since shortly after the multi-month eruption began in May.

Unprecedented damage to the infrastructure and landscape, however, means that this will be anything but a walk in the park for the authorities.

Situated in the southeastern section of Hawaii’s Big Island, Hawaii Volcanoes National Park comprises 330,000 acres of volcanic land and viridian wilderness, including the ginormous Mauna Loa volcano and the continuously active Kilauea. It was recognised in 1980 by UNESCO as a World Biosphere Site, and as a World Heritage Site in 1987.

This dynamic environment has seen its share of natural disasters over the years, but 2018 has been an especially wild ride. In addition to Kiluaea’s eruption, the park has had to deal with two hurricanes, a tropical storm and a prolific bushfire that engulfed 3700 acres of land.

Recovery efforts have been, and continue to be, multidisciplinary and comprehensive. From geomorphologists to landscape architects, NPS staff are making careful decisions day by day about what parts of the park can be re-opened, and what cannot. Those decisions have to be made not just based on safety, but budget too.

“Managing a National Park is like managing a small city,” park superintendent Cindy Orlando told us.

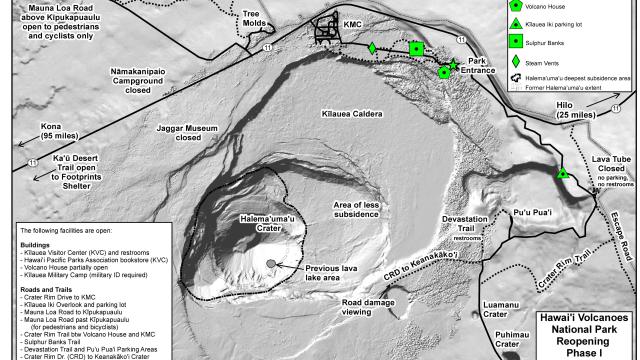

Plenty of facilities will be available to visitors again from this weekend, including the Kilauea Visitor Center, the Mauna Loa Road and the Kilauea Iki Overlook.

However, parts of Kilauea’s summit will remain permanently closed simply because of its instability. Out-of-bounds hotspots, such as the progressive collapse of the Halema’uma’u summit crater.

Ultimately, the NPS needs to make sure water is safe to drink, streets are safe to walk down, and lava tubes are safe to venture into again.

A major issue is uncertainty about the future. Kilauea’s eruption has certainly paused, but how do we know it’s stopped?

During the event, the summit crater lost its lava lake, expanded, and swallowed up the land around it. At the same time, billions of litres of lava emerged from a family of fissures in the Lower East Rift Zone.

Today, the summit is eerily silent, and the lava flows are transforming into Earth’s youngest land as they continue to cool. Acidic plumes of laze — steam containing hydrochloric acid droplets and very fine volcanic glass fragments — are no longer towering above lava entry points along the coast.

Fissure 8, which became the predominant lava producer in the latter stages of the eruption, is now inactive and surrounded by a crumbling volcanic cone. It is all over?

Mike Poland, Scientist-in-Charge at the US Geological Survey’s Yellowstone Volcano Observatory, was one of many USGS experts from around the US recruited to help monitor the eruption. He told us that the sudden cessation in summit subsidence more than a month ago “is one indication that this might be something more than a pause — but it’s so very hard to say”.

In the past two centuries of observation, the USGS has never seen an eruption so big over so short a time, so predictions will prove tricky. Poland stressed that there is clearly magma at shallow levels beneath the Lower East Rift Zone, “so we need to be wary”.

Wendy Stovall, a senior volcanologist at the USGS, shared similar sentiments. Magma will be resupplied to Kilauea, and as has happened several times throughout written history, lava will eventually return to the summit. “Right now, we don’t know how that will manifest,” Stovall told us, adding that a lava lake, lava fountains or explosive eruptions are all possible scenarios.

Some uncertainty will always exist, but as Orlando pointed out, this area is in a constant state of flux. “This is the only National Park that gains new land over time,” Orlando said. “Because we are an active volcano, we are always normally operating in a somewhat fragile atmosphere and environment.”

The USGS’s Hawaii Volcano Observatory will continue to monitor Kilauea, but based on what the NPS is hearing from scientists, a partial re-opening is now possible.

September 22 happens to be National Public Lands Day in the US, where visits to National Parks are free of charge. The team over at Hawaii found out after they set this as the re-opening date that this year’s theme is resilience and restoration, which couldn’t be more apt.

The NPS isn’t just focusing on making the park safe for humans again. Every decision to rebuild, remove or replace human structures also involves minimising the impact on wildlife. It’s difficult, at present, to know how those wildlife are faring.

Patrick Hart, a professor of biology at the University of Hawaii at Hilo, suspects the ecological damage was more extensive this time around compared to past eruptions.

It took out a large area of some of what’s left of the lowland ʻŌhiʻa forest, trees that are known for being particularly hardy and able to colonise fresh lava flows. This is particularly distressing, as the trees had just begun to recover from an aggressive fungal disease.

“Puna is one of the last places in the state where native forest comes all the way down to the ocean, and some of that was destroyed,” Hart explained to us. Some patches still remain in land not inundated by lava, which means they can be used to kick-start the recolonisation of the newest lava. But even with ideal management practices, “it will take about 150 years for the forest to regenerate to what it was,” Hart said.

The recovery of animals in the area will vary, but there’s certainly hope. Hart gives special attention to the lowland population of Hawaii ‘amakihi birds, of which he suspects some managed to escape to intact forest. He hopes they will be able to make a quick return to the impacted, but not destroyed, forests nearer the lava flows.

People that were displaced by the eruption are also being permitted to return. Earlier this month, the County of Hawaii rescinded mandatory evacuation orders for the affected regions, allowing residents of Leilani Estates (located northeast of the park) and those beyond key checkpoints limited access to the area.

Many, however, don’t have a home to return to, and those that do may find their house has been severely damaged by the lava.

“Obviously, the human impact — lost homes, lost revenue, lost peace of mind, loss of normalcy in day to day life — has been tremendous,” Janet Babb, a geologist and spokesperson for the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory, told us.

Kelly Wooten, an eruption information specialist with the Hawaii County Civil Defence, told us that even if they weren’t destroyed, plenty of homes remain inaccessible because of the complications involved crossing lava flows. In addition, fallout debris from the volcano “still covers homes and structures in neighbourhoods making it difficult to re-inhabit some areas”.

Babb emphasised that recovery isn’t just a matter of moving people back in, but “helping people get their lives back to normal, whatever that might be”.

Even as people return to the public and private lands affected by the eruption, risks are still present. Stovall explained that right now, a key hazard is walking across new, partly solidified lava flows, which can still collapse underfoot. Thicker parts of the lava will also remain incredibly hot for months to come.

The summit crater, which expanded greatly during the eruption, is also unsafe to approach. And the ocean entry points, although not the laze-producing factories they once were, remain dangerous.

Orlando stressed that while guests are welcome to visit the park, they must be aware of the constantly evolving hazardous nature of parts of it. They’re expecting a sizable influx of visitors during opening week, as people come to see how the landscape has been scarred and altered since it closed back in May.

No-one doubts that the recovery from the latest eruption is going to take many years. According to Wooten, “some places will never be the same.” But thanks to the herculean efforts of the communities, scientists and NPS staff involved, huge strides have been made already.

“[W]e are writing the next chapter of the park’s history,” Orlando said.