A new study of dogs published this week in Science offers a tantalising glimpse of how life-changing the gene-editing technology CRISPR could be for some people in the near future. It suggests that CRISPR can be used to treat an otherwise incurable, fatal genetic disorder known as Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD).

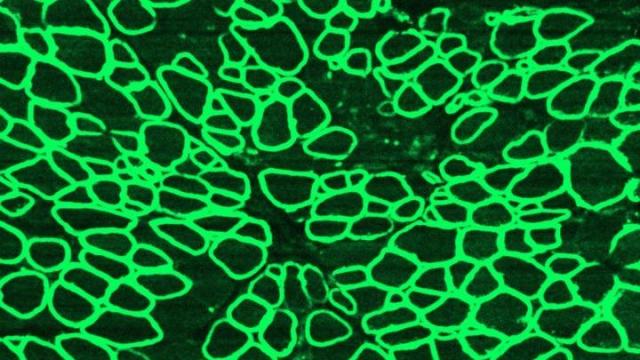

DMD is the most common form of muscular dystrophy, a blanket term for conditions that progressively destroy muscle throughout the body. This wasting away is primarily caused by the inability to use dystrophin, a protein that acts as a glue to stabilise muscle fibre.

These conditions are often caused by a genetic defect, and people with DMD have mutations in the gene responsible for dystrophin that prevent them from making any at all.

Because the dystrophin gene is found on the X chromosome, DMD primarily affects boys, since girls typically have two X chromosomes, and one healthy copy of the dystrophin gene is usually enough to prevent serious disease (women can still be carriers and pass on the disease to their sons though).

The symptoms of DMD show up around age four and only get worse over time, with many sufferers eventually losing the ability to stand, walk, and even swallow their food. And few live past the age of 30.

But, as seen with girls, it doesn’t take much dystrophin production to stave off these symptoms. So it’s been hoped that gene therapy could greatly improve the lives of sufferers or even cure the disease entirely.

The advent of the CRISPR-Cas system, a relatively cheap and easy gene-editing method, has only further raised that hope.

Already, there have been successful studies involving mice that used CRISPR to repair DMD mutations, which seemed to restore some muscle functionality — including by the team behind this latest study. Their new study is the first to test out whether the same could be seen in larger animals.

A few years back, it was discovered that dogs could be born with mutations that made them develop their own version of DMD, making them an ideal test animal. This mutation deletes a specific region of DNA on the dystrophin gene that codes for the protein, known as exon 50. Without this exon, exon 51 goes out of whack too, making dystrophin production impossible.

The researchers bred four beagles with DMD, then used CRISPR to edit exon 51, riddling it with errors. These errors, it was theorised, would cause the body’s affected cells to skip exon 51 altogether. The expected net result would be a reduced but still functional level of dystrophin production. And that’s apparently what happened.

The dogs were given CRISPR — via a harmless virus that makes its home in heart and muscle tissue — at one month old. Six to eight weeks later, the researchers found that dystrophin levels were 92 per cent and 56 per cent back to normal in the heart and diaphragm, respectively, in the dog that had received the largest dose.

It’s thought that even 15 per cent of normal dystrophin production would be life-altering for DMD sufferers.

“Our strategy is different from other therapeutic approaches for DMD because it edits the mutation that causes the disease and restores normal expression of the repaired dystrophin,” said lead author Leonela Amoasii, a researcher at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, in a statement. “But we have more to do before we can use this clinically.”

For one, the study was only meant to be a preliminary demonstration, so the dramatic results should be taken with caution for now. The dogs weren’t even observed long enough to know for sure whether this restoration would lead to a sustained improvement in symptoms. (They were euthanised to avoid subjecting them to any potential suffering that could result from the condition and treatment.)

Further, only around 15 per cent of people with DMD have this particular mutation, so other gene edits would be needed to help out the rest of the some-300,000 boys worldwide believed to have the condition.

And for the praise CRISPR has gotten, there are real, if sometimes overstated, fears it could cause unwanted gene mutations that can raise the risk of cancer or other health problems. If CRISPR treatments for DMD targeted a person’s stem cells, the authors noted in their study, both the beneficial and harmful effects could be permanent.

There were no specific off-target mutations seen with the dogs, but it’s a risk other future studies will have to continue watching out for.

Still, the researchers, who have formed a company to commercialise their technology, called Exonics Therapeutics, are eager to keep pursuing larger and longer-term studies involving not just DMD but other genetic disorders as well.

[Science]