Gun violence moves through a city the way a virus moves the body: predictably, but with uncanny precision. New research suggests “virus” patterns can be spotted and possibly help predict and even prevent shootings. But questions remain of whether this can be done ethically, and, most crucially, who can be trusted with this predictive technology.

Visualisation: Jim Cooke/Gizmodo

A recent study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association uses contagion models to track and predict the next victims of gun violence. The authors, Yale sociology professor and Chicago native Andrew Papachristos, and Harvard students Ben Green and Thibault Morel, studied nine years of gun violence data from Chicago, totaling over 13,000 shootings. The arrest records, along with the info on gun violence, were sourced from the Chicago Police Department (the dataset excluded suicide, accidental discharges and police shootings). The researchers concluded that bullets follow a path of familiarity, spreading in a pattern resembling a virus.

“[Gang violence] looks more like a blood-borne pathogen than it does a flu, per say,” Papachristos told Gizmodo. “You don’t catch a bullet like you catch a cold, [but] the power of this analogy is really thinking about the precision with which it moves through a population.”

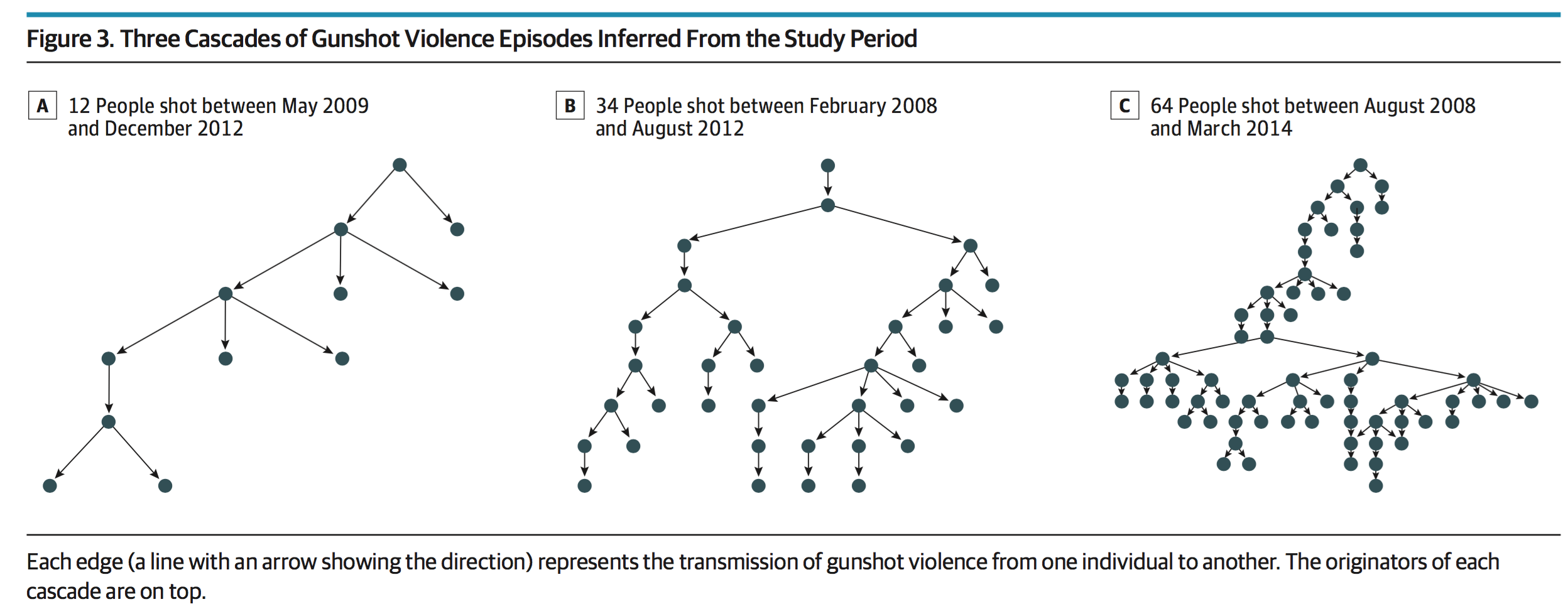

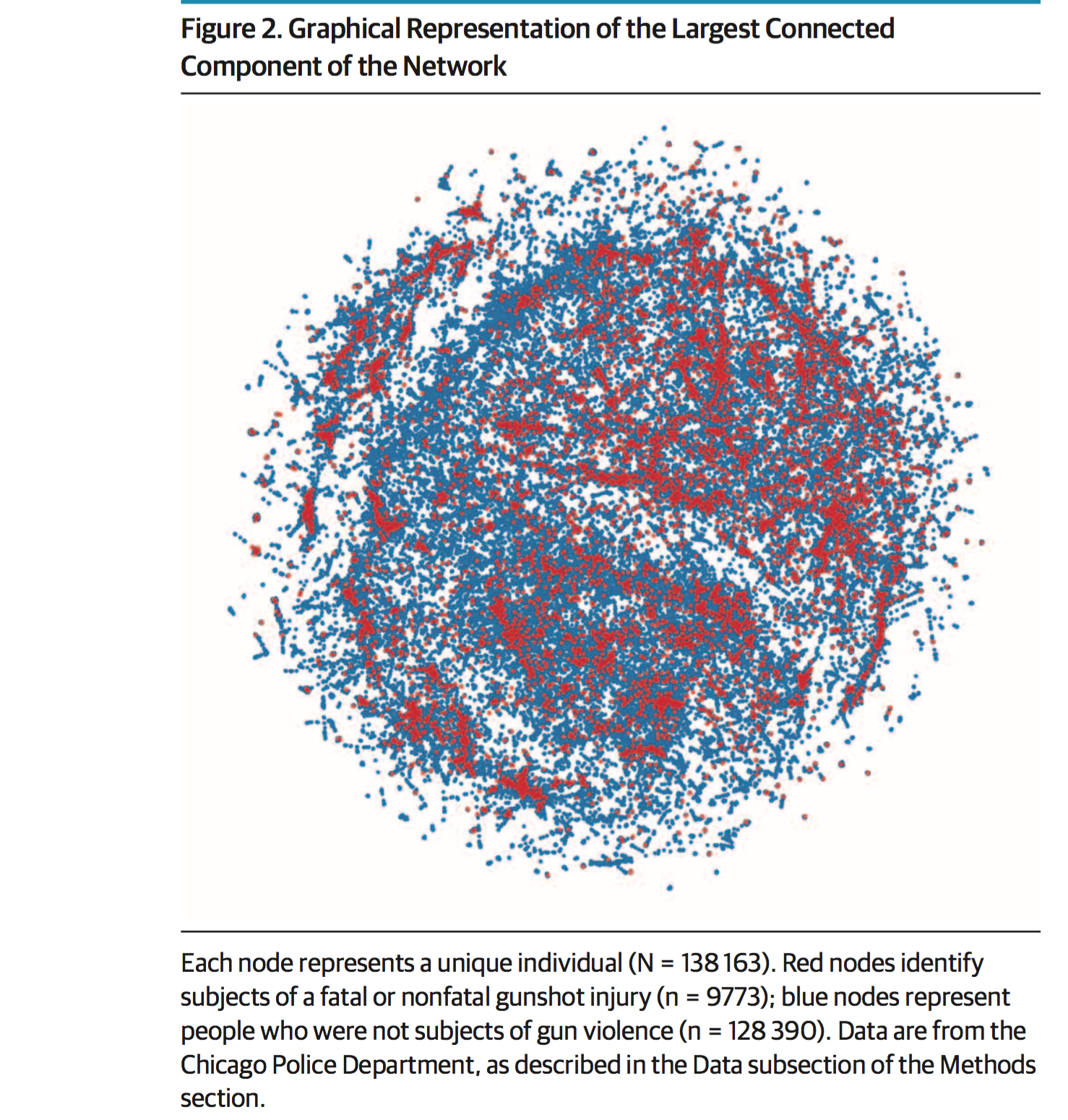

Image: Green B, Horel T, Papachristos AV. Modelling Contagion Through Social Networks to Explain and Predict Gunshot Violence in Chicago, 2006 to 2014

Papachristos suggests that riding in a gang means taking on all the grudges and affiliations of people in the same crew. So, per his example, a trip to the 7-Eleven turns deadly for Individual A because he arrives with Individual B, who has beef with rival gang members already present when they arrive. Individual A has no beef with them, and may not have been targeted if he’d arrived alone.

Thus, in this analogy, Individual B has “infected” Individual A with gun violence, meaning Individual B’s influence has made Individual A a target. Papachristos and his colleagues found that gun violence “moved” in Chicago like HIV — appearing predictably within a concentrated network in social interactions that involve “risky” behaviour.

“Any good preacher, teacher, cop, football coach, they know these networks,” he said. “They live in these networks. But they only see a small part of it. We’ve just provided a whole map.”

To create the map, the researchers looked at pairs of Chicago residents who co-offended (meaning they were arrested together), creating a complex social network of 138, 163 individuals. Within this network, gun violence emanated outwards from one victim, “infecting” the people around him. The closer you were to someone who was just shot, the more likely you were to soon be shot yourself. Seventy per cent of nonfatal gun violence could be tracked to networks containing less than 5 per cent of the city’s population — the victims and perpetrators were usually in overlapping social circles.

Green B, Horel T, Papachristos AV. Modelling Contagion Through Social Networks to Explain and Predict Gunshot Violence in Chicago, 2006 to 2014

In theory, knowing who is most likely to be shot offers a chance to intervene and save lives. Papachristos says he imagines a localised rapid response system where nonprofits will offer their services to someone the system flags. But others have voiced serious ethical concerns with the use of predicative models, specifically, in law enforcement. Jessica Saunders, a senior criminologist with nonprofit RAND Corporation who studies the efficacy of predictive technologies, says researchers who rely on data from law enforcement may be working on incomplete data, skewing the results.

“My real big problem,” Saunders said, “is that we are taking these predictions and pretending they’re accurately predicting the real truth.”

Saunders pointed out that any law enforcement biases that went into compiling a criminal dataset will likely become embedded into statistical models and their resultant extrapolations. (These biases, which include racial profiling and the overpolicing of black and Latino neighbourhoods, can be observed in the analysis of NYPD and CPD arrest and stop-and-frisk data. Bias is also evident in the likelihood of police violence towards people of colour — the kind of violence not factored into this specific study.)

Incomplete data becomes a serious problem as predictive technology becomes more and more commonplace.

“At least 40 per cent of crimes aren’t reported,” she said. “So if you build these complicated, sophisticated models on incomplete data, all you’re doing is replicating whatever bias there was in inputting the data.”

Without safeguards to prevent bias from creeping into statistical models, or prevent misuse of the information those models deliver, what “could” happen is terrifying. The ACLU’s Jay Stanley imagines a Black Mirror-esque dystopian future where all citizens are given predictive criminality/at-risk scores, which cops are able to see via augmented reality Google glasses. It sounds like a nightmarish invasion of privacy, but the technology to make it happen exists: augmented reality is common place, body camera manufactures are already exploring face recognition technologies (Google bans them on Glass), and here, we have the calculative potential to Minority Report someone’s chance of committing a future crime.

ACLU: Chicago Police “Heat List” Renews Old Fears About Government Flagging and Tagging

Papachristos acknowledges the possibility for overreach, but says he envisions his models being used by non-profits to create a holistic approach to gun violence prevention that includes offering potential victims resources like health care, employment, education with a much higher degree of specificity.

“We’re trying to move the dialogue about saving the lives of these young men, most of whom have a criminal record, as the focus as opposed to saying, you know, let’s just throw more policing resources at them,” Papachristos said.

Although predictive technologies present a certain vision of the future, the specifics 0f how they will be used going forward are not clear. Looking at the many barriers to fairness and transparency we see in the present evinces there’s still much work to be done to prevent abuse. It’s pointless to predict gun violence if those predictions only serve as statistical justification for biased police overreach.

Saunders and Papachristos are both against police using statistical data to target anyone, but neither can predict that they won’t. As Papachristos put it, “I can’t control what people are gonna do with the work that we’ve done.”