IMAGE: Getty Images

Earlier this month, a new study came out suggesting that it’s possible to predict whether a toddler will become a criminal. Based on neurological exams, scientists correlated the brain health of people at age three with whether they went on to commit any crimes as adults. And for those with poor brain health, 80 per cent of the time, it turned out that they did.

The study nabbed headlines around the world suggesting that we’d arrived at a “Minority Report” future in which a person could be condemned based on a 45-minute brain test alone. Cue the outrage.

The only trouble is, that’s not actually what the study found.

The headlines in question come to us via the Dunedin Study, a massive research effort that began in New Zealand in the 1970s to follow 1,000 people beginning at birth. Over the past four decades, the study has netted many important findings, among them revelations about why people age differently, what leads to substance abuse and how early childhood experiences shape adult life. In the most recent research, the study’s authors were looking to test the idea that a small per cent of the population accounts for a large percentage of social service recipients, and then figure out whether there might be early identifiers to help figure out which segments of the population are most in need of preventative services.

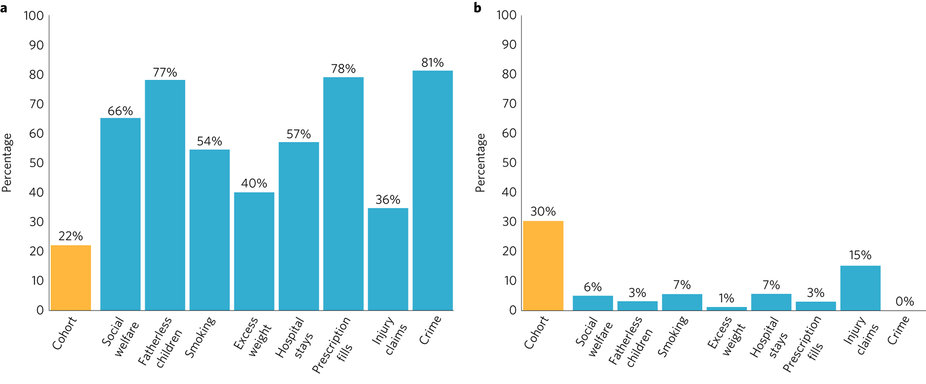

Researchers dug through decades of health and government records for the study’s 1,000 participants, finding that within the cohort, 80 per cent of economic burden was attributable to just 20 per cent of its members. That small slice accounted for 81 per cent of the group’s criminal convictions, 66 per cent of welfare benefits, 78 per cent of prescription fillings and 40 per cent of those considered obese. Researchers also looked at the results of a pediatric examination each study member had done at age three, back in the 1970s. The examination included a neurological evaluation assessing verbal comprehension, language development, motor skills and social behaviour. Poor scores on that test, they found, were a good indication that a person would wind up a member of the “high cost” group. In fact, by looking at those scores, they could guess who would end up in which group about 80 per cent of the time.

The end goal, study director Richie Poulton told me earlier this week, is to help health and education providers better target their services at those most in need.

“We have all of this education and preventative programming,” he said. “But so often those services do not get to the people who need them the most.”

But online, this research got boiled down, essentially, to one click-worthy pull quote: “Future criminals revealed at three,” as one headline put it. Poulton said the headlines were “unfortunate,” distracting from the findings with Orwellian fear-mongering.

The researchers were conscious of how their results might be interpreted. In their paper, published in Nature Human Behaviour under the much less buzzworthy heading “Childhood forecasting of a small segment of the population with large economic burden,” researchers wrote that they were “aware of the potential for misusing these findings, for stigmatising and stereotyping.” It’s implications, though, suggested the opposite: “There is no merit in blaming a person for economic burden following from childhood disadvantage,” the wrote.

Fake news, in all its varied iterations, is high on the list of our current moment’s trending topics. But it is an issue that has long plagued science. Studies get twisted or simplified to the point of no longer being true, reduced to a headline that each time it’s retweeted or reblogged gets further and further from the truth. Sometimes pure fiction makes its way into the public consciousness as fact. Every year, the British Medical Journal publishes an issue of joke science, but years later, those papers wind up being cited as real. Earlier this year, when I was reporting on the biotech company Oxitec’s quest to release genetically modified, disease-fighting mosquitoes in the Florida Keys, project scientist Derric Nimmo told me he had taken to going door-to-door in the Keys in an attempt to fight rumour with fact. Rumours included one that the modified mosquitoes could make children sterile and another that the company was actually the cause of Zika’s spread.

The reason this matters is that the science that is permitted to progress is the result of not just technological progress, but also politics and ethics. The headlines heralding that Dunedin Study researchers have created an early-warning system for criminals aren’t just wrong — they could impact, say, whether those researchers get precious funding dollars in the future.

Among scientists, the notion that childhood risk factors can be useful predictors of events later in life is controversial. Dunedin Study researchers sought to use their decades of data to weigh in. This new research is another point in the debate, suggesting that certain childhood risk factors could indeed be useful to public health policy-makers in determining who is most in need of preventative services.

“We sought to inform a question that nags at the behavioural and social sciences, and that has strategic consequences for national policy on children: how strong is the connection between childhood risk and future costly life-course outcomes?” they wrote. “Results reported here suggest that the importance of childhood risks for poor adult outcomes has generally been underestimated.”

A shows the burdens on society of multiple-high-cost users. B shows that in contrast, a substantial segment of the cohort did not belong to any high-cost group. IMAGE: Nature

Some of the findings were in line with what other researchers have suggested. They found that members of the high-cost group had the same four childhood disadvantages: they grew up poor, were mistreated, scored low on IQ tests, and exhibited a lack of self-control. But while those numbers led to a statistically significant prediction when looking at the group as a whole, they didn’t help predict what might happen to a certain individual. That’s where the neurological assessments came in. A simple, 45-minute neurological exam, they found, could be an extremely accurate predictor of whether an individual would heavily rely on social and health services later in life. This could, in theory, help providers target specific individuals from a young age with services to help them stay on the straight and narrow.

“Ameliorating the effects of childhood disadvantage is an important aim,” the researchers wrote, “and achieving this through early-years support for families and children could benefit all members of a society.”

The research of course still needs to be replicated and put through real world tests to see whether identifying such people early on might have a positive effect. In the meantime, though, turning science fact into science fiction benefits no one.