New York Times reporter David Sanger worked extensively with former deputy CIA director Michael Morell during the reporting of his book Confront and Conceal: Obama’s Secret Wars and Surprising Use of American Power — even arranging to provide Morell with access to an entire unpublished chapter for his review — according to documents obtained by Gizmodo.

Photos: Getty Images

The records, consisting of internal emails from the CIA press office, show that Sanger met with Morell on more than one occasion in 2012 to discuss his then-forthcoming book, promising to bring with him a full chapter for Morell to read in case “he has issues” with the reporting. The emails, which we received under the Freedom of Information Act, are redacted in a manner suggesting that Morell and Sanger discussed sensitive national security information, and show that on at least one occasion, a CIA public affairs officer sent Sanger an encrypted message via email.

While the notion of a national security reporter meeting with a senior CIA official is obviously not unusual — such transactions are in the reporter’s job description, and Sanger’s book acknowledges that he withheld information at the request of government officials — the extent of Sanger’s collaboration with Morell and the fact that the men apparently discussed sensitive information is noteworthy in light of the Obama administration’s unprecedented campaign against government leakers.

Indeed, another high-level Obama Administration official — four-star Marine General James Cartwright — was recently convicted of lying to US federal agents who were investigating his contacts with Sanger. According to Politico, prosecutors accused Cartwright of “provid[ing] and confirm[ing] classified information, including TOP SECRET/SCI information” to the Times reporter. In particular, Cartwright was reportedly believed by prosecutors to have discussed details of the Stuxnet virus, the joint US-Israeli cyberattack on Iran’s nuclear program featured in Confront and Conceal. Morell, who left the CIA in 2013, has never been charged with leaking and played a prominent role advocating on behalf of Hillary Clinton in the 2016 campaign.

The emails released by the CIA reproduce Sanger’s correspondence with the agency’s press officer, Cynthia “Didi” Rapp, who acted as an intermediary when the two men weren’t in the same room. Many of them will strike reporters (and public relations professionals) as rather routine, and they do not contain explicit proof that Morell or any of his CIA colleagues provided Sanger with classified information. Rather, they appear to document Sanger’s efforts to fact-check portions of Confront and Conceal, as well as to give Morell an opportunity to request that sensitive details be withheld.

But they do suggest that Morell and Sanger discussed information that the US government considers unfit for publication. Several exchanges have been redacted by the CIA under what is known as the b(3) exemption, a provision in the FOIA that permits government censors to redact information barred from release by any other statutes aside from the FOIA. According to the CIA’s response to our request, “the relevant statutes” are the CIA Act of 1949 and the National Security Act of 1947. The CIA Act of 1949 gives the agency broad authority to bar the release of information that could undermine “the security of the foreign intelligence activities of the United States”. The relevant section of the National Security Act of 1947 states simply: “The Director of National Intelligence shall protect intelligence sources and methods from unauthorised disclosure.”

Many b(3) redactions appear to be for mundane things like names and titles of CIA officials. But the agency applied more extensive b(3) redactions to several emails in which Sanger discussed a particular chapter of Confront and Conceal.

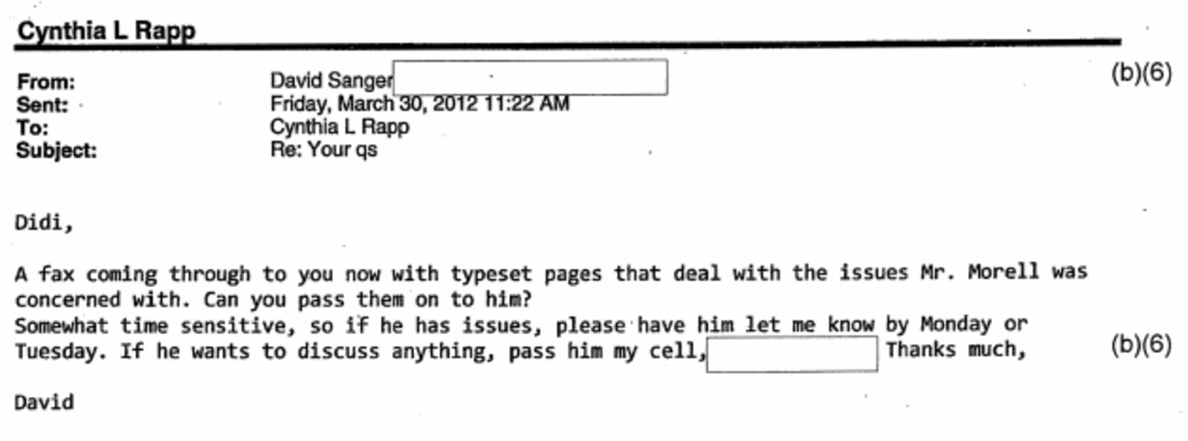

Beginning in late March 2012, Sanger began undertaking to provide substantial portions of the draft — parts that, according to the emails, “Mr Morell was concerned with” — to Morell for his review. First, he faxed some typeset pages for Morell to read:

Source: Page 14 of FOIA request F-2012-01498

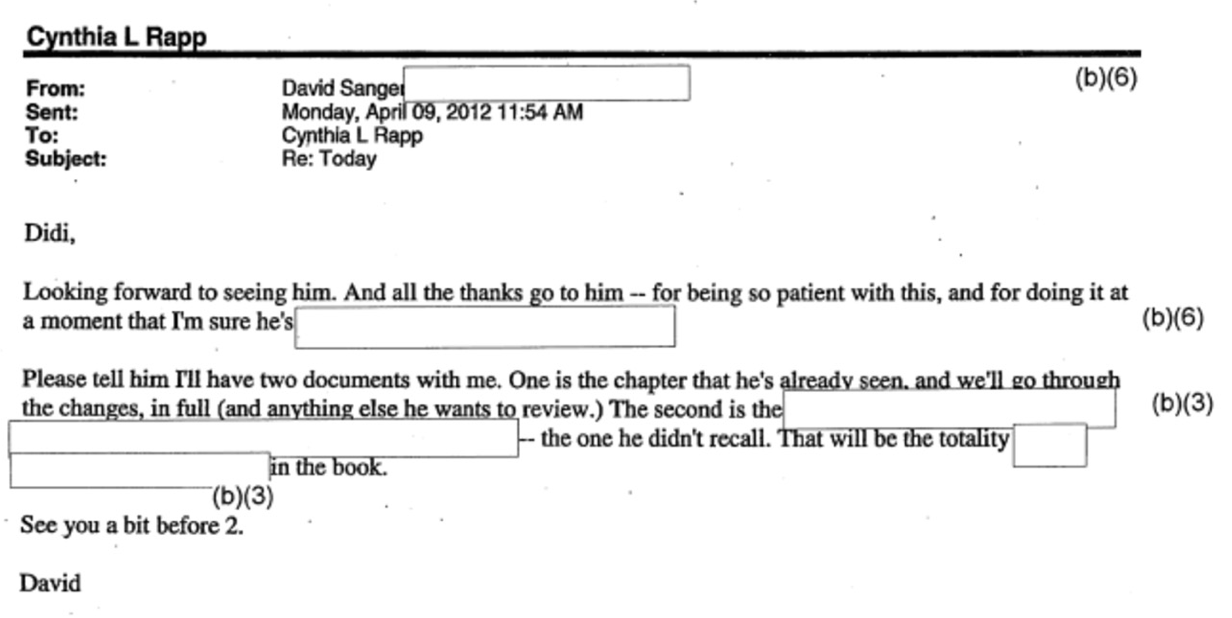

Rapp replied that Morell had reviewed the fax, but was “concerned that he isn’t seeing the whole flow, how the parts are fitting,” and asked to read the entire chapter. Sanger replied that, for security purposes, his publisher wouldn’t permit him to email an entire chapter for review. But he did agree to bring a copy physically for Morell to read in his presence. The emails setting up that meeting contain information that the CIA redacted using its b(3) authority — in other words, details the disclosure of which could harm “the security of the foreign intelligence activities of the United States”.

Source: Page 7 of FOIA request F-2012-01498

Source: Page 8 of FOIA request F-2012-01498

The Central Intelligence Agency denied that Morell, or any other CIA employee, provided classified information to Sanger. “Unfortunately, CIA is often queried by reporters who have received sensitive information from other sources,” the agency’s spokesperson, Dean Boyd, told Gizmodo. “In such scenarios, CIA works hard to keep such information from being published. While these interactions are difficult and not always successful from CIA’s perspective, they are necessary to protect national security.”

Morell, who now works in the private sector, also denied that he shared any classified information with Sanger. He added that he met with the journalist at the “explicit request of senior White House officials” and that “a senior CIA officer joined me for the meetings with Mr Sanger”. After noting that the Justice Department was made aware of his meetings with Sanger, Morell cautioned against reading too much into them, given the nature of the resulting book. “My meetings with Mr Sanger or the results of those meetings did not, in any way suggest [or] imply that the CIA, or the Executive Branch, approved of (or was OK with) what he was publishing,” he said.

While it’s considered unusual for reporters to share full drafts of their reporting with sources, it seems to be distressingly common on the CIA beat. In 2014, the Intercept reported that Los Angeles Times reporter Ken Dilanian (who later joined the Associated Press and now works for NBC News) had sent unpublished drafts of stories to the CIA press office for review. Los Angeles Times standards bar the practice, and Dilanian told the Intercept at the time that he “shouldn’t have done it”. In 2012, just a few months after Sanger shared his work with Morell, his New York Times colleague Mark Mazetti was caught sending a CIA public affairs officer an advance copy of a Maureen Dowd column. The Times doesn’t have formal rules governing sharing stories in advance, but a spokesman told Politico at the time that “this action was a mistake that is not consistent with New York Times standards”. While the Times excerpted a portion of Confront and Conceal, Sanger appears to have been contacting Morell in his capacity as an author, rather than a reporter for the Times.

General Cartwright acknowledged in late October that he had spoken with Sanger, as well as Daniel Klaidman of Newsweek, and pleaded guilty to misleading US federal investigators about his contact with the reporters. But he did not plead guilty to actually disclosing classified information. Following his plea, Cartwright’s attorney clarified that his client was trying to protect such information, not disseminate it: “In his conversations with these two reporters, Gen Cartwright was engaged in a well-known and understood practice of attempting to save national secrets, not disclosing classified information.” Neither Sanger nor Klaidman have acknowledged or discussed their contacts with Cartwright.

General Cartwright’s defence is almost identical to the explanations given by the CIA and Morell for Morell’s willingness to engage with Sanger. The similarity raises questions, at the very least, about the line between discussing classified information and trying to stanch its dissemination, and the consequences of not knowing where that line may be.

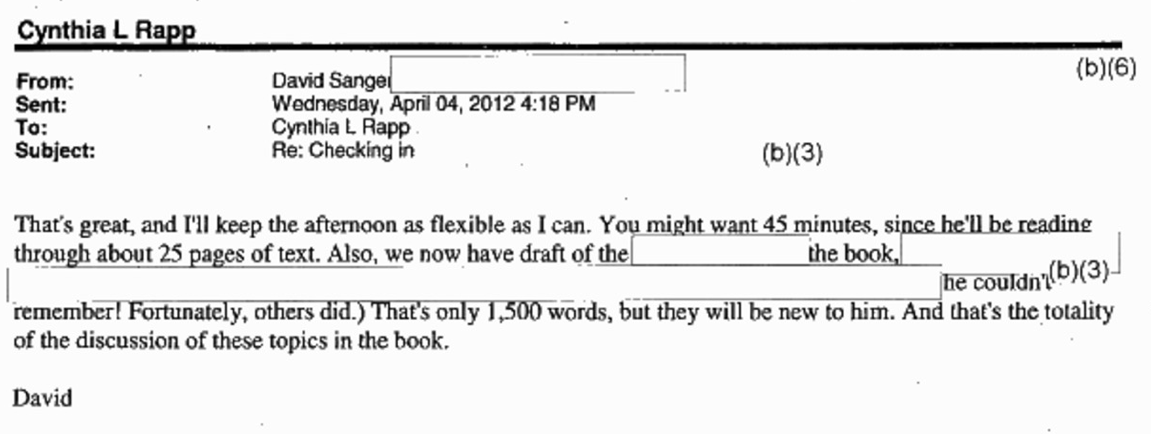

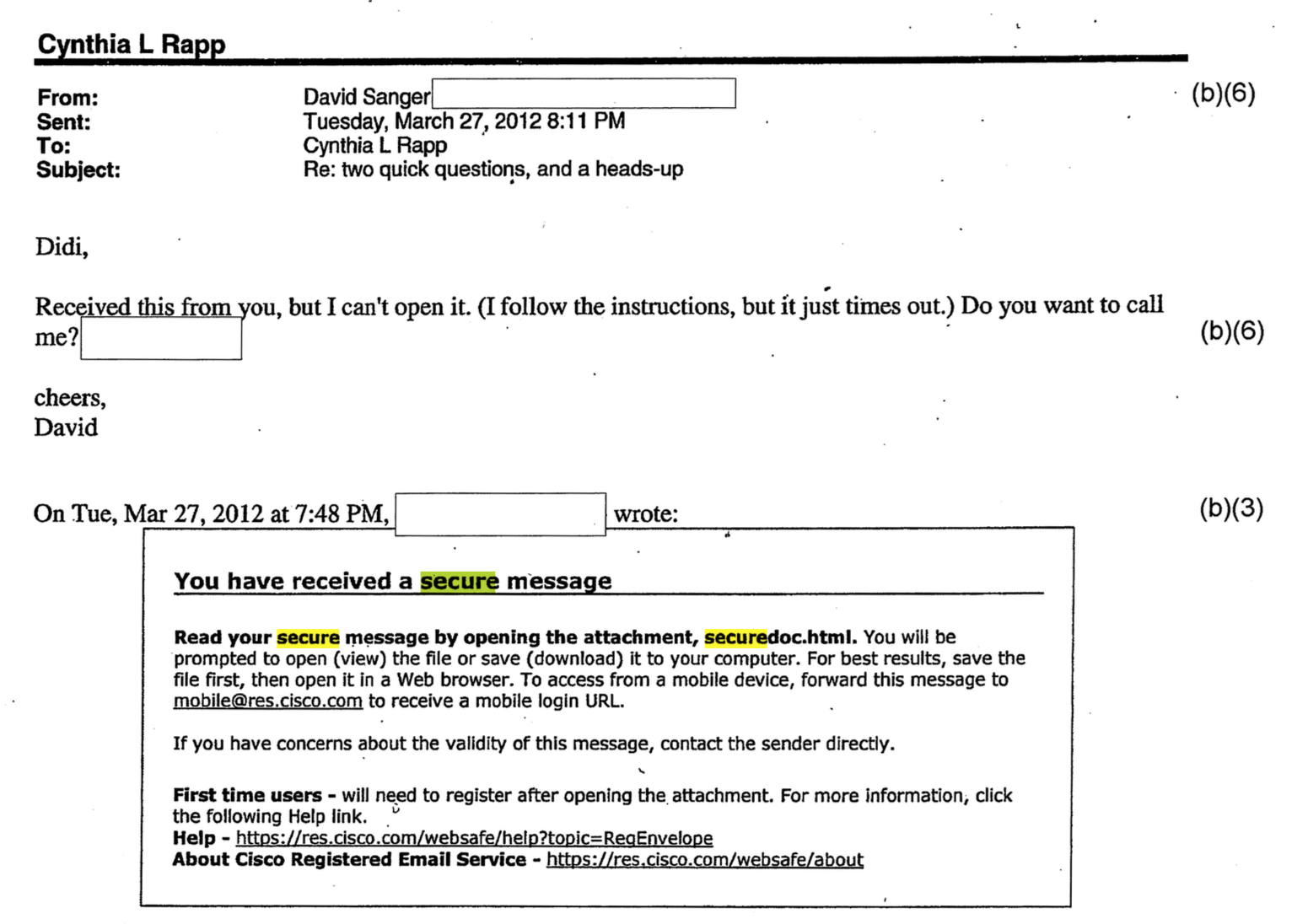

The strongest indication that Morell and Sanger were discussing topics that the US government was interested in protecting from prying eyes is the fact that Rapp attempted to encrypt at least one message to Sanger. In an email dated 27 March 2012, Rapp is seen sending Sanger a “secure message” via Cisco’s “registered email service”:

Source: Page 17 of FOIA request F-2012-01498

Sanger apparently had trouble opening the message, and the emails we received don’t indicate why Rapp sent it in the first place. Generally speaking, however, Cisco’s secure email system, which the company describes as a “cloud-based encryption-key service”, is designed to ensure that information sent with it remains confidential, often to comply with federal regulations like the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996. The CIA already operates a secure, and entirely separate, system for transmitting classified information to cleared personnel, so it’s not immediately obvious why the agency would use Cisco’s service in a message to a third-party — especially a reporter. And, perhaps more importantly, the contents of that message were not included in the emails released to Gizmodo.

The agency says that Rapp’s “secure message” to Sanger was not sent intentionally, but rather triggered by network issues the agency was experiencing in late March of 2012. “Given the network performance issues on March 27-28, 2012, the only message to reach Mr Sanger from the CIA press officer in this particular exchange was a standard auto-message generated by a network device,” said Dean Boyd, the CIA spokesperson. To corroborate this explanation, Boyd pointed to other messages around the time period in which Rapp alerted Sanger that the agency had experienced some sort of network interruption.

Cisco, for its part, would not comment on Rapp’s use of its secure email system, and declined to even confirm that the CIA contracts with the company. “Cisco does not publicly discuss our customers, so we cannot confirm for you whether a specific agency uses Cisco technology in their network,” said spokeswoman Yvonne Malmgren.

The contents of the secure message, whatever they may be, were not the only records excluded from the released documents. Our original request, filed in 2012, sought “all correspondence, electronic or otherwise, between any staffers in the Agency’s Office of Public Affairs and the following persons: David E. Sanger, reporter for the New York Times and author of Confront and Conceal“. However, Rapp’s emails with Sanger indicate that both parties exchanged correspondence that didn’t make it into the documents released by the CIA.

For example, the fax of typeset pages Sanger sent to Morell wasn’t included in the release. And, on March 29, Rapp emailed Sanger with a message referring to some sort of annotated document (“comments to your comments in blue”) that appears nowhere in the released records:

Source: Page 14 of FOIA request F-2012-01498

(The CIA press office declined to elaborate on why these referenced records were not included with the other emails, and we have filed a formal appeal seeking their release with the agency’s Information and Privacy Coordinator.)

None of the parties involved in Sanger’s writing — the Times; Sanger’s publisher, Crown Books; and Sanger himself — would comment on the record about the author’s communications with the CIA. “We’re just not getting into the reporting process,” Sanger said. (In a later message, he said that his email about sending Rapp “typeset pages” was “self-explanatory”.) However, Confront and Conceal acknowledges, in its section of sourcing, that its author consulted government officials about withholding sensitive information:

Following the practice of the Times in reporting on national security, I discussed with senior government officials the potential risks of publication of sensitive information that touches ongoing intelligence operations. At the government’s request, and in consultation with editors, I withheld a limited number of details that senior government officials said could jeopardize current or planned operations.

Elsewhere in the same section, Sanger thanks Rapp (along with several other officials at the White House and the State Department) for arranging interviews with high-ranking government officials. Several of these officials, Sanger notes, “would be horrified, or fired, if I named them here”. The book does not identify Morell as a source.

We’ll probably never know what exactly Michael Morell told David Sanger. But the circumstances of their meetings — the White House’s orders to Morell; Rapp’s assistance in arranging their meetings; the presence of a senior CIA official — clearly demonstrates that Morell was never in fear of being fired.

We’ll also probably never know what General Cartwright told Sanger, either. Like Morell, he insists that he endeavoured to guard classified information, not leak it. And, despite his conviction for lying, federal investigators never proved that Cartwright actually leaked anything sensitive. The distinction between Cartwright and Morell, then, seems to be less about the Obama administration’s fear of classified information falling into the wrong hands, and more about its desire to exercise control over the stories being told about it.