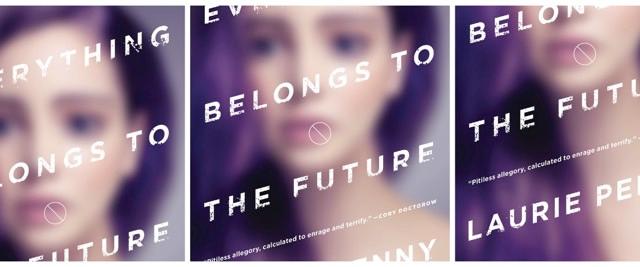

In Laurie Penny’s new novella, Everything Belongs to the Future, a miracle drug can extend the human lifespan by centuries — but only the rich can afford the treatments. It’s a science fiction thriller that feels like an only slightly tilted version of our own reality, and we have an exclusive excerpt to share.

Here’s the official summary:

Time is a weapon wielded by the rich, who have excess of it, against the rest, who must trade every breath of it against the promise of another day’s food and shelter. What kind of world have we made, where human beings can live centuries if only they can afford the fix? What kind of creatures have we become? The same as we always were, but keener.

In the ancient heart of Oxford University, the ultra-rich celebrate their vastly extended lifespans. But a few surprises are in store for them. From Nina and Alex, Margo and Fidget, scruffy anarchists sharing living space with an ever-shifting cast of crusty punks and lost kids. And also from the scientist who invented the longevity treatment in the first place.

Laurie Penny’s Everything Belongs to the Future is a bloody-minded tale of time, betrayal, desperation, and hope — available October 18th from Tor.com Publishing.

Get more of a taste in this fast-paced excerpt, which expands quite a bit on the pages previously posted by publishers Tor.com:

There was a wall. It was taller than it seemed and set back a little from the street, so the ancient trees on the college side provided a well of darker shadow, away from the streetlights.

The wall was old and rough, ancient sandstone filled in with reinforced cement to keep out intruders. The drop on the other side landed you in thick grass. Still, Alex was afraid of the wall. Of the idea of it.

Nina was the first to make the climb. She squatted on top of the wall, an implike thing in the darkness. Then she turned and held out her hand to Alex, beckoning.

“You have to see this,” she said.

Alex started to climb the wall between the worlds. The old stone bit at his hands. Halfway up, he heard Nina make a little sound of disappointment in her throat. He was never fast enough for her.

The approach to Magdalen College was across the deer park.

That was where they were going: through the park, avoiding the dogs and the security lights, into the college, into the ball all sparkling under the starlight.

It was four of them, Nina and Alex, Margo and Fidget, and they were off to rob the rich and feed the poor. An exercise, as Margo put it, as important for the emotional welfare of the autonomous individual as it was for the collective. Margo was a state therapist before she came to Cowley, to bunker down with the rest of the strays and degenerates clinging to the underside of Oxford city. Five years of living off the grid hadn’t cured her of the talk.

At the top of the wall, Alex unfolded himself for an instant, and then he saw it — what Nina had been trying to show him. The old college lit from behind with a hundred moving lights, butter-soft and pink and pretty, a bubble of beauty floating on the skin of time.

“It’s beautiful,” he said.

“Come on,” said Margo, “get moving, or we’ll be seen.”

Margo was beside him now, the great bulk of her making no sound on the ascent. Alex’s mouth had been dry all night. He licked his teeth and listened to his heart shake the bars of his rib cage. He had promised the others that he was good for this. He wasn’t going to have another anxiety attack and ruin everything.

“As your therapist,” said Margo, gentling her voice, “I should remind you that God hates a coward.”

Alex jumped before she could push him, and hit the grass on the other side of the wall without remembering to bend his knees. His ankles cried out on impact.

Then Nina was next to him, and Margo, all three of them together. Fidget was last, dropping over the wall without a sound, dark on dark in the moonlight. Margo held up a hand for assembly.

“Security’s not going to be tight on this side of the college. Let’s go over the drill if anyone gets caught.”

“We’re the hired entertainment and our passes got lost somewhere,” said Nina, stripping off her coverall. Underneath, she was wearing a series of intricately knotted bedsheets, and the overall effect was somewhere between appropriative and indecent.

Alex liked it.

“Alex,” said Margo, “I want to hear it from you. What are you?”

“I’m a stupid drunk entertainer and I’m not being paid enough for this,” Alex repeated.

“Good. Now, as your therapist, I advise you to run very fast, meet us at the fountain, take nothing except what we came for, and for fuck’s sake, don’t get caught.”

Fireworks bloomed and snickered in the sky over the deer park. Chill fingers of light and laughter uncurled from the ancient college. They moved off separately across the dark field to the perimeter.

Alex squinted to make out the deer, but the herd was elsewhere, sheltering from the revelry. The last wild deer in England. Oxford guarded its treasures, flesh and stone both.

Alex kept low, and he had almost made it to the wall when a searchlight swung around, pinning him there.

Alex was an insect frozen against the sandstone.

Alex couldn’t remember who he was supposed to be.

Alex was about to fuck this up for everyone and get them all sent to jail before they’d even got what they came for.

Hands on Alex’s neck, soft, desperate, and a small firm body pinning him against the wall. Fidget. Fidget, kissing him sloppily, fumbling with the buttons on his shirt, both of them caught in the beam of light.

“Play along,” Fidget hissed, and Alex understood. He groaned theatrically as Fidget ran hard hands through his hair and kissed his open mouth. Alex had never kissed another man like this before, and he was too shit-scared to wonder whether he liked it, because if they couldn’t convince whoever was on the other end of that searchlight that they were a couple of drunks who’d left the party to fuck, they were both going to jail.

The searchlight lingered.

Fidget ran a sharp, scoundrel tongue along Alex’s neck. A spike of anger stabbed Alex in the base of his belly, but instead of punching Fidget in his pretty face, he grabbed his head, twisted it up and kissed him again.

The searchlight lingered, trembling.

Fidget fumbled with Alex’s belt buckle.

The searchlight moved on.

Fidget sighed in the merciful darkness. “I thought I was going to have to escalate for a second there.”

“You seemed to be having a good time,” said Alex.

“Don’t flatter yourself,” said Fidget. “The word you’re looking for is ‘thanks.’”

They were almost inside. Just behind the last fence, Magdalen ball was blossoming into being. Behind the fence, airy music from somewhere out of time would be rising over the lacquered heads of five hundred guests in suits and rented ballgowns. Entertainers and waitstaff in themed costumes would be circling with trays of champagne flutes. Chocolates and cocaine would be laid out in intricate lines on silver dishes.

Alex and the others weren’t here for any of that.

They were here for the fix.

Daisy Craver had come to this party under protest. Her company liked to show her off at events like these, just another expensive decoration in this stage-managed whirl of decadence they were sponsoring. That’s what Daisy was to them — a prestige piece. No different from the biosculptures in the lobby at the lab. She hadn’t done any real work in years.

Instead, she got wheeled out to these things like an angry puppet to pick at ridiculous miniature food and talk to brainless, braying rich kids and their parents, who were all just so grateful for her research. At least, the parents were. The kids probably hated her — sure, they got to be young and healthy for an extra half-century, but Mummy and Daddy got that same half-century to spend the inheritance. Without that, they were having to find other ways to maintain the lifestyles to which they had become accustomed.

“It will be good for you.” That’s what Parker had said. Parker was Daisy’s supervisor, although she thought of him as her handler. What he meant was “it will be good for us.” The work she had done back in the twenties was essential to the base formula of the fix, and that made her essential to the company. An important resource, they said. Like all the other geniuses who got the life-extension grants.

Daisy didn’t take it as a compliment. She knew what multinationals did with important resources.

Still, she put on the stupid frock with the ruffles that neither suited nor fit her and got in the limo, and now she was hanging around the fountain, eating chocolate-covered marshmallows and trying to avoid the undergraduates in their prom gowns and penguin suits. Parker wanted her to show her face. He never specified that there should be a smile on it.

Daisy hated parties, and this one was particularly hateful, a shaken snow globe of opulence just begging to be dashed on the floor. The theme was “The Fountain of Youth.” It was based on a weird old racist novel where some British explorers went to darkest Africa and discovered a tribe of savages ruled by an immortal queen who was for some reason as white as they were.

The theme had been chosen in honour of the sponsor, Daisy’s own company, TeamThreeHundred, which held the patent for the broadest-spectrum life-extension drugs on the market. The distinctive little blue pills went for two hundred dollars a pop on the black market — less if you could afford the right insurance. One pill a day, every day, was enough to keep your meat fresh for decades and more. There were people who’d started to fix fifty years before who hadn’t counted a single grey hair.

Rich people, mostly, and anyone deemed socially useful enough that their continued existence was worth sponsoring, although that too was up to the manufacturers to decide. Artists, musicians, scientists. Even the occasional writer. Meritocracy in action.

Daisy had never liked parties, though — even when she was young, really young, not just young-looking. Not that she ever got invited to many parties back in school. Not that she had cared. More time to spend on the net, talking to professors three times her age about gene splicing.

Daisy had been born at the turn of this millennium, on the exact day that the completion of the Human Genome Project had been announced to the world. She had seen it in the old stills — the government scientist and the venture capitalist standing on either side of the president at the time, one of the Clintons or one of the Bushes, all their differences buried in public, a new dawn for the future of biotech.

None of these kids necking free cocktails would remember. Even the ones who were already fixing — and Daisy could tell, she could always tell; there was an uncanny smoothness to the skin, a ghastly glisten that made them doll-like. They wouldn’t be old enough to remember a time when money could only buy, at best, the appearance of youth.

The fountain was the centrepiece. The old stone sprinkler with its constipated-looking cherubs had been decked out as the Fountain of Youth, but it was only running cheap champagne, cut with Prosecco.

It was the little dishes around the side that held the real juice. Candy bowls of blue pills. Fashioned like arrows, more precious than diamonds. The fix. Free to those who could afford it, courtesy of our generous sponsors.

Daisy was alone.

These days, she was always alone.

She opened her tablet and called up an old video. Scrubbed from the net now, but she had a copy. Pixelated, seventy years old, but the sound was clear.

A dark stage. A quiet audience of professionals. A single podium, and there she was — a much younger, identical-looking Daisy, giving one of the last unscripted ethics talks she had ever got away with.

“The mould strain Aspergillus aevitas is native to Orkney in the Republic of Scotland. Since its discovery and cultivation by my department, the Future of Humanity Institute at Oxford, and following development by TeamThreeHundred, this fungus has made the dream of significantly extending not just human life but human youth a reality.

“Thank you. In the course of my research for the company, completed with my coauthor Doctor Saladin Hasan, I was an early recipient of TeamThreeHundred’s extension program. At forty years old, I have the vital statistics of a person less than half my age. With regular treatment, I can expect to live well into the next century without any deterioration in quality of life.”

Applause from the audience, most of whom, Daisy reflected, would be long dead by now, except those with company health plans.

“Thank you. I hope that these extra years of useful work will be as much of an asset to the department and the company that sponsored this groundbreaking research as they will be of personal benefit to me. You’ve heard from people far higher up in the company how those who are now receiving the second generation of extension treatments can expect to live some three centuries, barring accidents and acts of God. You still need to look both ways before you cross the road. Ahaha. Yes. That’s the line we’re all using today. How did I do?

“Anyway, it remains to be seen what the effects of this miraculous technology will be on the world our grandchildren inherit — although perhaps I shouldn’t use the word ‘inherit,’ since I fully intend to be around to see it myself.”

More applause from the audience of ghosts.

“Thank you. I’m here today as a technologist, but also as a scholar of the history of science. History shows us that the ramifications of any new technology have as much to do with how we choose to distribute it as they have to do with the technology itself. I am not a politician, nor am I an economist. I am a scientist. But it seems appropriate to hypothesize here that a future where life-extension technology is available only to those who can afford it, or to those whom society considers useful, will look very different to a future where life-extension technology is more broadly available. I’m sorry —

“I’m sorry, something seems to have gone wrong with the sound . . .”

A noise behind Daisy. Parker Tremaine walked heavily across the damp grass, carrying two glasses of champagne. Knowing Parker, it’d be the good stuff.

She darkened her tablet quickly, and the ghost of her younger self disappeared, too late for him to miss. Aside from being the closest she still had to a direct boss, Parker was the one person in the entire company who had been been fixed for as long as she had, back when he was an entrepreneurial prodigy in the early days of T3, in what later became the Free State of California.

They knew each other too well for her to hide things from him.

“Memory lane?” he asked. He still had the lazy West-Coast accent. “Here. I brought us some bubbly. We’re due a chat, you and me.”

“No, thanks.” Daisy patted her hip flask. “Whisky only.”

“Suit yourself. More for me.” Parker downed one glass in a single fizzy swig and tossed it away over the lawn. He was already drunk.

They looked out together over the college lawns, toward the hills of Headington. A small forest of turbines churned away on the horizon. There were hardly any in the old city.

“It’s amazing, when you think about how it used to be,” said Parker quietly.

Daisy took a swig. “Not going to argue with you on that.”

It was always somebody else’s apocalypse. Until it wasn’t.

The end of the world was an endless dark tomorrow: always arriving but never actually here. For generations, the elected and unelected leaders of the world had weighed the cost of averting drastic climate change via collective, immediate and lasting technological investment against the considerable inconvenience to their personal lifestyles, done some calculations on the back of a napkin and come up with the answer that it was somebody else’s problem. Somebody who probably hadn’t been born yet. If all else failed, their own children and grandchildren would probably be able to afford a place on the last helicopter out of the drowning lands. So, that was alright.

The fix changed everything.

Suddenly, the same people had to plan for a future in which they’d actually be around to see London and New York swallowed by the hungry ocean. Suddenly, the end of the world was a story about them.

The solutions came fast. But not fast enough to save Bangladesh. Or Venice. Or San Francisco.

“In all the world, we’re the only two creatures quite like us,” said Parker after a while. He lifted his second glass of champagne and looked at Daisy. “Remind me again why we’ve never fucked?”

“That’s easy,” said Daisy. “It’s because I don’t fancy you.”

For an instant, a flicker of real, childlike anger chased across Parker’s cherub face, and was gone. He ran his fingers through his perfect blond hair and smiled.

“Ever considered lesbianism?”

“Thoroughly. And regularly. You know I prefer dicks when they’re attached to women.”

This was a complete and utter lie. Daisy had not had sex in ten years. Daisy had not had fun of any kind since she could remember, but particularly not horizontal fun involving other humans. Keeping her appearance static at awkward mid-puberty helped with that. It was one of the few decisions she’d never regretted. Plenty of people might like the idea of an eternal fourteen-year-old, but they changed their tune when they met her, all gangly limbs and acne scars and flashes of anger.

A long time ago, there had been someone who’d seen past her defences. Someone who’d made her feel that she was more than a brain trapped in a twist of preserved flesh, a specimen suspended in amber. Someone who had loved her — actively, he always said, because love is not something you feel but something you do.

But he had been dead these forty years.

Daisy picked at her fingernail and glared at Parker.

“Actually,” she said, “speaking of dicks attached to women, where’s your better half? Lila, wasn’t it? I liked her. She was funny.”

Parker went quiet.

“We had different life goals,” he said eventually.

“She wouldn’t fix, would she?”

Parker’s expression twisted and flushed. There was something truly unnerving, Daisy thought, about watching extremely good-looking people trying not to cry, like seeing a beautiful painting slashed and torn.

“Bitch,” said Parker.

He took a deep breath and put his face back into his champagne. Daisy swigged from her hip flask.

“I know what you’re up to,” he said quietly.

“If you did, you wouldn’t say so,” she said.

“You want to be careful,” he said. “You haven’t got many friends in this company, you know. If it wasn’t for my vouching for you — ”

“I haven’t got any friends in this company,” said Daisy. “‘Friend’ is not the correct word for what you are to me. Friends don’t veto friends’ research proposals. Or read friends’ internal mail.”

“Alright,” said Parker. “Alright. I tried. Don’t say I didn’t try.”

“Nice catching up,” said Daisy. “Let’s do it again in a decade or so.”

Daisy watched him leave.

When she was sure he was out of sight, she went back to scanning the crowd.

Somewhere here, somebody else didn’t belong.

She would find them. She was waiting.

By one in the morning, the ball had taken on that manic edge every party develops when people have accepted that it’s going to hurt tomorrow and only care about delaying the pain as long as possible. Even the hired entertainers, dressed up in janky rags and ooga-booga tribal outfits, circulating among the undergraduates in their tuxes and ballgowns, were getting sloppy. One of them even dropped a tray of little blue pills.

Fidget and Nina saw it happen and rushed in to clear up the mess, sweeping most of it into the padded pockets sewn into their costumes. They were here, after all, to steal as much as they could.

Alex watched them move, wondering what it would be like to move like that, with such bold, casual grace. Maybe you had to be born an artist. He fumbled for a cigarette.

A sharp suck and a slow burn at the back of his throat. A rush of smoke cooled from the lungs, slow-trickled over the teeth, the scrag of rolled tobacco scraps in the mouth and this is the way the world ends — not with a bang but a bonfire.

Nina was suddenly behind him, winding her arms around him, sweet and fast. Her pockets already packed with pills.

“When are we distributing all these, again?” Alex brought his mouth down to Nina’s level so he could murmur in her ear.

She just giggled. “Need to know,” she said.

“You never tell me anything anymore.” Alex squeezed her arm. “I’m starting to think you’ve gone off me.”

“Never-not-ever.”

“Or maybe you think I’m police.”

Alex said it casually, teasing her. Teasing himself. Made it a joke, deflecting her attention. And it wasn’t precisely a lie — he wasn’t police; the company employed him to spy on activists. In three years doing this job, he was sure Nina hadn’t suspected a thing.

Alex wasn’t a bad person. He spent a significant amount of time feeling horrible about the whole thing. Especially since he’d got truly fond of them all. Especially since he and Nina had become a thing.

The problem was, love turned out to be the perfect cover. A white-hot thread of emotion was strung between them, and he spooled it out and pulled it tight, careful not to let it slacken. He did this daily, diligently, with the practice of a professional, and the fact that he really did love her too only made the act more convincing.

He hadn’t expected to fall in love, doing this job. Sex, yes, that was understood and even encouraged as part of his cover. A tacitly understood perk. Forge strong relationships, his supervisor had told him after he was seconded to the company. Translation: fuck whoever you like. But Nina — Nina was different. Some girls you fucked, and some girls you married, and some girls were different from all the others. You’d find one of them in a lifetime, maybe, if you were lucky.

Nina was a wonder. A dream in the shape of a girl.

He wasn’t going to let go of her.

A breath, a beat. The music stopped.

Then the applause, the whooping of undergraduates who had been drinking since noon.

Alex and Nina swayed together, watching the debutantes dance.

“It’s different for them,” said Nina, after a while, “these kids. They will never have what we have.”

“What do you mean?”

“Think about it. You only have a few years to be young, and you’re spending them with me. Isn’t that marvellous?” She took both his hands and spun in them, wrapping herself in his arms. The feel of her small, tight body warm against him.

“You don’t ever feel like we deserve another decade or two?”

“Everyone deserves it,” said Nina. “But I don’t want it until everyone gets it.”

Alex palmed a couple of pills from his pocket. Little blue jewels. He held one up to the hollow of her throat.

“Look,” he said, “I stole you a diamond.” He lifted it to her lips.

“Don’t eat the fairy food,” she said, smiling a smile that didn’t reach her eyes. She was trying to be cute, but it was still a warning.

“Nobody would know.”

“I’d know,” she said, swatting his hand away. “Be serious.”

Alex was being serious. When Nina furrowed her brow in annoyance, which she did often, the lines took a few seconds to disappear. That was new. Pretty soon, she wouldn’t be his girl anymore. She’d still be his, but she wouldn’t be a girl. He wished that didn’t matter, but it did.

“I’m cross with you now,” said Nina. “You’ll have to kiss it away.”

So, he kissed her. She tasted of champagne and hormones; the taut firm weight of her in his hands as he dipped her back, putting on a show for the drunk undergraduates. A smattering of applause.

“See?” she whispered into his mouth. “They won’t remember tonight. We will. When you have less time, all of this matters more.”

But Alex knew it mattered less.

Nina disappeared to charm some more fix from the fountain-stands. Alex watched her go, the roll and bounce of her walk, and thought, without guilt, of his wife. Ex-wife in all but name. Helen had asked for a divorce three years before. After he took this job. After it became clear that the undercover work was going to be long-term.

“You don’t belong here.”

Alex turned around as slowly as he could without acknowledging the statement.

“I’m right, aren’t I? You don’t belong here.”

The speaker was a little girl in a dress that she was not so much wearing as occupying under protest. Her bony arms and legs poked out of a confection of pink frills and expensive lace that neither fit nor suited her, and despite the copious champagne on offer, the girl was swigging what looked like neat whisky, swirling in a small tumbler. A slick of lipstick threw her scowl into sharp relief. She looked like an angry macaron.

“I’m with the entertainment,” said Alex. “My pass — ”

“Got lost, right?”

The girl laughed and pulled a lanyard from somewhere in her frills. The TeamThreeHundred logo winked on the all-access pass, blue and green and sickly.

“I saw the guest list,” said the girl. “You and your friends aren’t on it. That makes you the most interesting thing at this otherwise boring, shitty party.”

Alex said nothing. He made fists to stop his hands darting to the pouch of pills in the folds of his own outfit.

“We’ll do a deal,” said the girl. “You tell me why you’re really here, and I won’t call security right now.”

“That’s really not going to work out well for you,” said Alex. Whoever this girl was, she had enough access to see the guest list but not enough to know that the company employed freelance undercovers.

“Oh, yes? Why’s that?”

Just as Alex opened his mouth, he felt Nina slip a hand into the crook of his elbow.

“Is there a problem?” said Nina, putting on the sweet-and-probably-a-bit-stupid smile she reserved for authority figures who got between her and a clean getaway. “We’re with the entertainment.”

Alex groaned inwardly. Nina’s sweet-and-stupid-smile trick worked on everyone except other young women.

“Please,” said the girl, “let’s not patronize each other. I have a proposal you’re going to want to hear.”

Nina dropped the smile like a hot dish.

“Do we have a choice?” she said. All business now.

“Oh, yes,” said the girl. “You can choose to help me have a less boring evening, or you can choose to explain to college security and to my employers why you invaded this party, because it wasn’t for the free booze.”

The girl sat down and patted the wall beside her. When Nina sat down, the girl nodded and knocked back the rest of her whisky, and tossed away the tumbler. It shattered on the flagstones with a satisfying crash.

“Aren’t you too young to drink?” said Alex.

The girl pinned him with a look that made Alex think of dissection tables. “I’m ninety-eight years old,” she said.

Alex stared.

“That’s not possible,” he said, doing the calculations in his head.

“The first fix only got FDA approval seventy-six years ago,” said Nina.

“I know,” said the girl, “I helped write the patent. You’ve got some pretty specific knowledge for a hired stripper.”

“That’s a bit sexist.”

“The world is a bit sexist. I’m Daisy. Professor Daisy Craver, currently for TeamThreeHundred.”

She held out a skinny, nail-bitten hand. Nina shook it carefully, like a package that might explode.

“And what should I call you?”

Nina shook her head. “Call security, if you’re going to,” she said.

“No, I don’t think I will. Not yet. Nice outfit, by the way,” said the girl.

“Thanks,” said Nina. “I like yours.”

“Don’t lie. Liars are boring,” said the girl. “Tell me what you’re stealing the product for and I won’t tell on you. Black market?”

“No.”

“Personal use?”

Alex moistened his lips. It had not failed to occur to him that the pills Nina was carrying could, in theory, give them both an extra three years if they rationed them all for themselves.

“No.”

“Now, that is interesting,” said Daisy. “What would you say if I told you I could get you as much as you want, without you having to sneak around in a bikini?”

“I’d assume you were wired to the teeth.”

“You’d regret it. Now, security will get wind of you soon, so I suggest you and your furry friends clear off sharpish. If you want to hear more, meet me in three days at Rose Hill Cemetery. Come alone, no backup, and so will I.”

The girl had clearly practiced that part of the speech. She fired it off all at once.

Alex was intrigued. His contacts would be intrigued too.

“We’ll meet you,” he said. “Where?”

“Can I have a cigarette before you go?” asked Daisy.

Smoking was an affectation shared almost exclusively by fixers and dirt-poor anti-gerontocracy activists with nihilist leanings. Fixers and wannabe fixers because it didn’t hurt them and was therefore a way of showing off. Nihilists because fuck it, weren’t they all going to die young anyway?

But Daisy Craver smoked in a different way. The same way Alex remembered his mother smoking after she got her final diagnosis. Sucking down each cigarette like it was her first and last.

She exhaled slowly through her nose.

“Fuck,” she said. “That’s delicious. Alright, go now. Rose Hill Cemetery, in three days. Bring bags like you’re foraging. If there’s anyone with me, keep walking. Now run away.”

They ran. Margo and Fidget saw them and ran too. The tall, thick grass of the deer park snatched at their limbs, like when you try to run away from a nameless enemy in a nightmare.

Alex would have a lot to report next time he saw Parker.

Laurie Penny’s Everything Belongs to the Future is out today.