For much of its modern history, science fiction has had a particular fascination with engineering, with authors and artists imagining fantastic, massive structures in the depths of space. Here are 10 of them, from incredibly large to unbelievably massive.

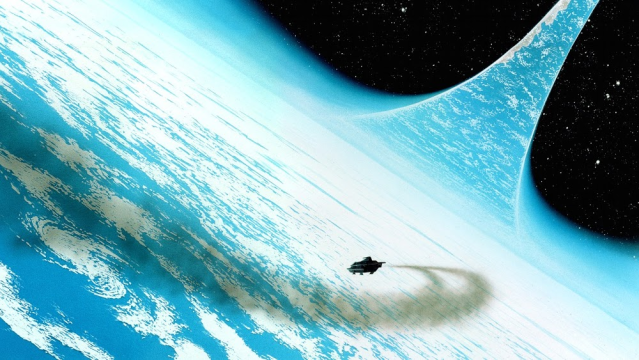

Image: Erik Wernquist

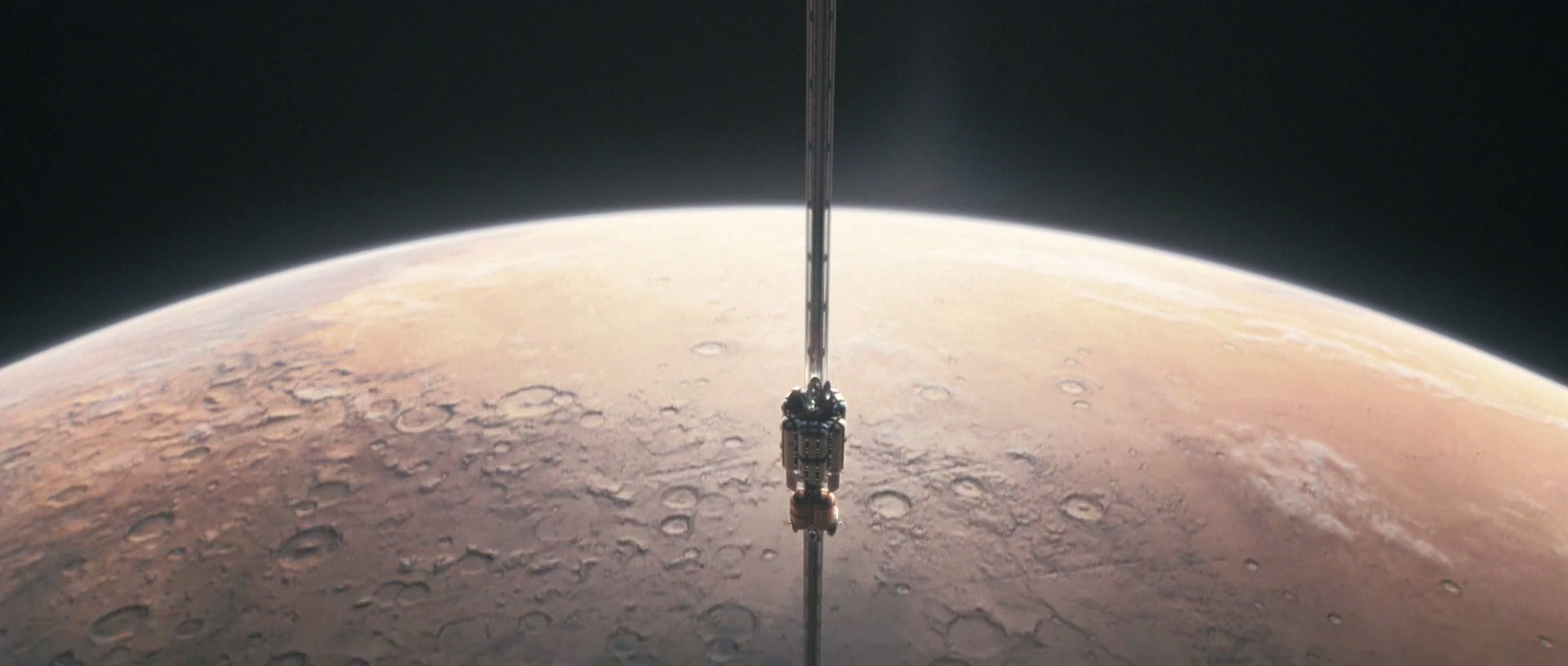

1) Space Elevator

Heralded as one of the ways to open up access to space permanently and cheaply, a space elevator is an anchored tether that extends into low orbit, allowing a car to carry people and cargo into space.

First conceived of as early as 1895, the space elevator is probably the easiest (and cheapest) to construct, with numerous studies already conducted on the feasibility of such a structure. The construction of such a structure would require extremely strong materials.

Another take on the concept is an Orbital Ring, cooked up by Nikola Tesla in the 1870s, which is a massive structure which circles the Earth, with tethers fixed to the ground that act as elevators.

Because they’re incredibly useful for getting into space, they pop up in science fiction often, such as in Kim Stanley Robinson’s novel 2312, Alastair Reynolds novels Blue Remembered Earth and Chasm City, Fountains of Paradise by Arthur C. Clarke and in shows such as Star Trek: Voyager and Halo: Forward Unto Dawn.

Image: Sony Pictures

2) Stanford Torus

This is the first and smallest of several ring-like habitats on this list. Conceived of in 1975 during a 10-week program in engineering systems design held at Stanford University and NASA’s Ames Research Center. It’s a self-enclosed torus 1.8km in diameter, and would rotate once per minute to provide its 10,000 inhabitants with 1.0g of gravity.

An inner ring is connected to the outer ring with a series of spokes, and provides sunlight set up with a system of mirrors, which provide light to the station.

The torus featured in Neill Blomkamp’s (underrated, IMO) 2013 film Elysium is similar to a Stanford Torus: It shares the dual ring and spoke construction, but is much, much larger at 40km in diameter and 2km across, housing 10 million of Earth’s wealthiest citizens. Unlike the Stanford Torus, it’s not an enclosed ring: The top is open to space, with the rotation and walls of the station holding in the installation’s atmosphere.

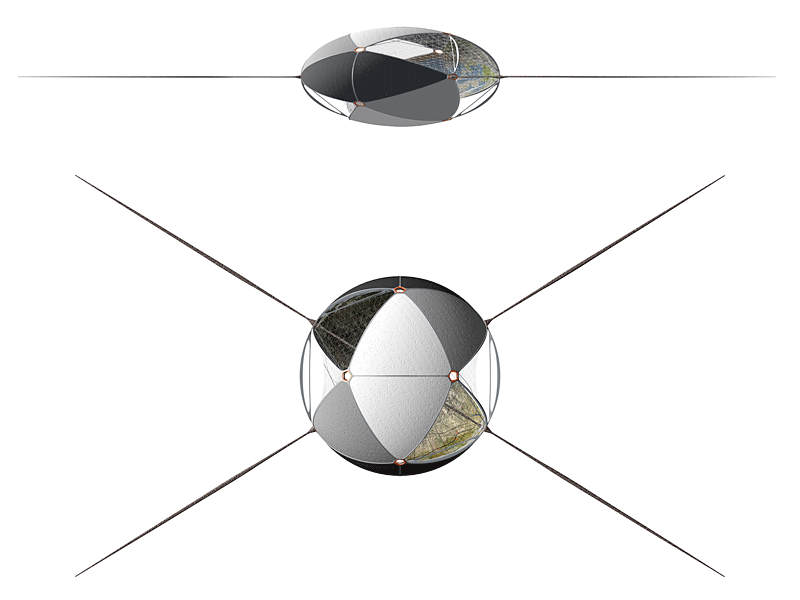

3) Bernal Sphere

The Bernal Sphere was first formally proposed in 1929 by John Desmond Bernal. The sphere is essentially a air-filled sphere, spun up to provide gravity to its inhabitants at the equator. The original idea was of a sphere 16km in diameter, which would provide living space for 20,000 to 30,000 people.

There’s a handful of examples of their use in science fiction, such as Gagarin Station in Mass Effect, as well as Kim Stanley Robinson’s Terrariums, hollowed-out asteroids with living spaces installed in their interiors used in his novel 2312.

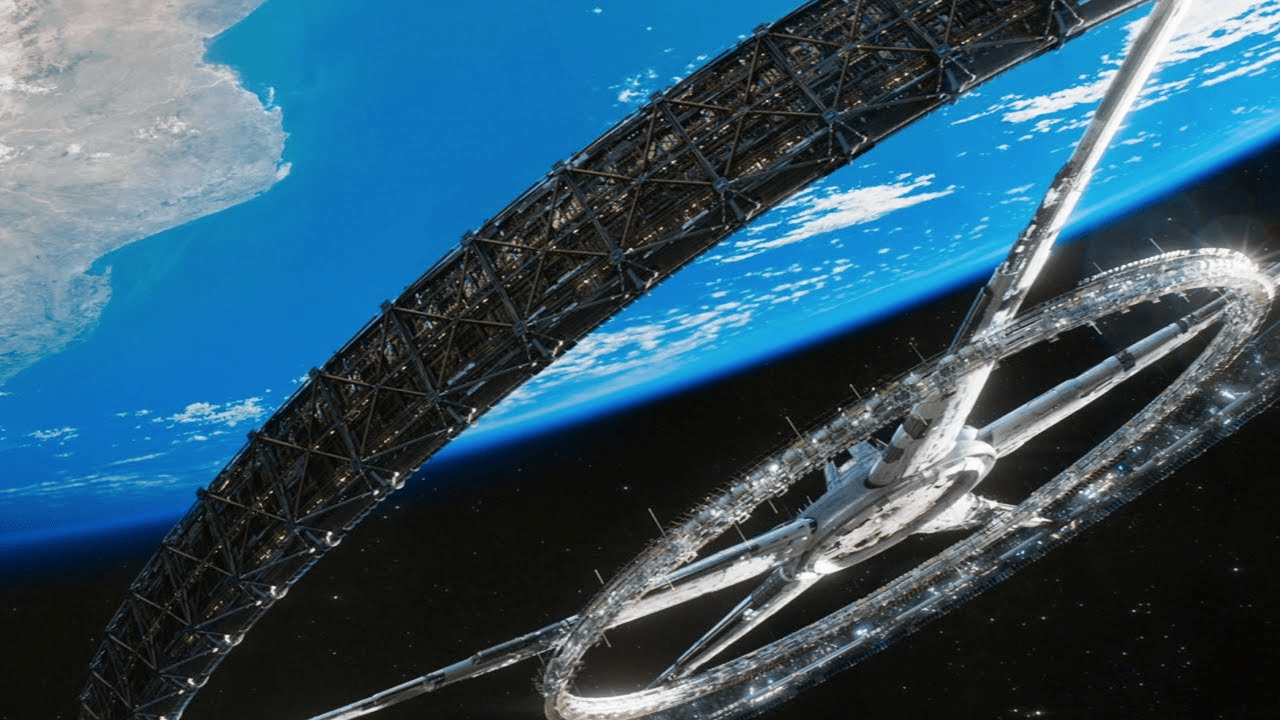

Image: Warner Brothers

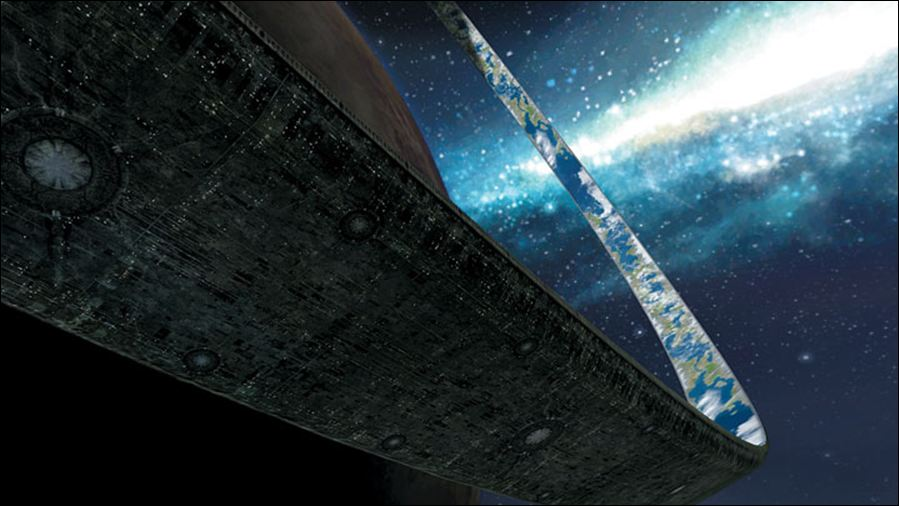

4) O’Neill Cylinder

In his 1976 book, The High Frontier: Human Colonies in Space, Gerard K. O’Neill worried about the possibility of humans overtaxing the Earth, and sought for alternatives. He noted that for long term sustainability, a space habitat would have to be self-sufficient, being able to produce its own food and have its own atmosphere.

These “islands in space” as he called them, would be massive: 6.5km in diameter, 32km long, they would contain 1300 square kilometres, and could house up to a million individuals, and that’s at the small end. The larger ones “could be fifteen miles [24km] in diameter, seventy-five miles [120km] long, and could have a total land area as much as seven thousand square miles [18,130 square kilometres]; about half that of Switzerland”.

These O’Neill cylinders would be fully enclosed, and would rotate to provide an Earth-equivalent gravity, and could be configured to have simulate daylight hours. A larger version of this is a Topopolis, which would be long enough to be looped around a star.

There are some notable examples of this in science fiction: The Babylon 5 station from the show of the same name, while another appears at the end of Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar.

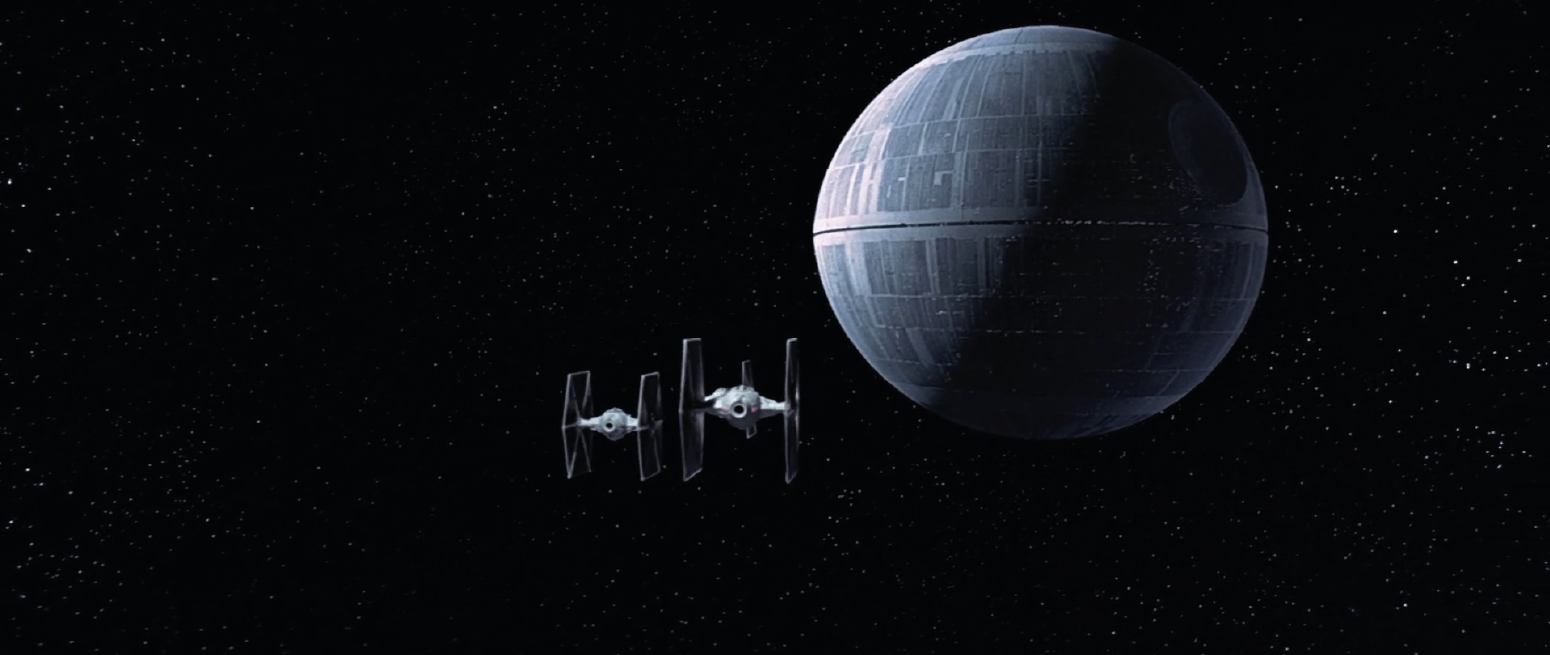

Image: Lucasfilm

5) Death Star

“That’s no moon.” The Death Star is possibly the most famous megastructure to exist in science fiction. Designed as a weapon of intimidation, they (their numbers depend on your reading of canon/non-canon sources) were commissioned to hold the Empire’s subjects in line by the threat of planetary destruction.

The Galactic Empire’s planet-killing installations rang in at 120 (A New Hope) and 160 (Return of the Jedi) kilometres in diameter (About the same size as Saturn’s moon Epimetheus and Uranus’s moon Puck), and housed upwards of the 1.7 million personnel required to run the installation.

A later regime would resurrect the concept with Starkiller Base, but build into a planet deep in the galaxy’s unknown regions.

Image: Christian Waldvogel

6) Globus Cassus

This structure was proposed in a design book in 2004 by Christian Waldvogel, a Swiss architect and artist. This structure is a compressed “geodesic icosahedron” with a pair of openings to let in light. At 85,000km in diameter, it would take all of Earth’s matter and turn it inside out in a giant shell, with habitable living space in the interior.

Halo installation. Image: Bungie

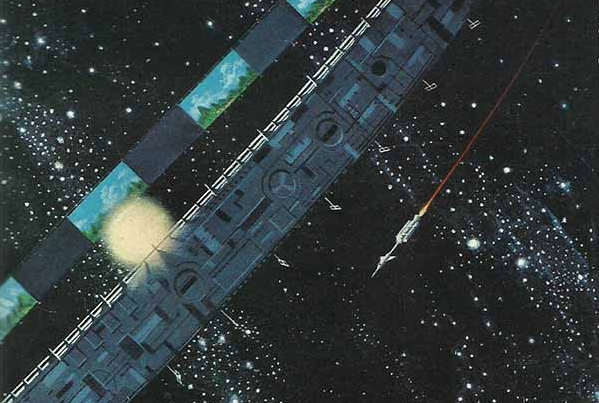

7) Ringworld

The titular location of Larry Niven’s novel Ringworld is an iconic science fictional megastruture. It’s massive: 965.6 million kilometres in circumference, 1.6 million kilometres wide and 1 AU in radii, providing an unimaginable amount of living space for a civilisation. The gravity created by the rotation of the structure keeps its citizens and atmospheres on steady footing on the inner edge of the ring, while day and night cycles are created with squares that orbit above the surface.

Ringworld. Art: Dean Ellis

Unlike the Stanford Torus, a ringworld designs predominantly feature a single, massive ring, sometimes surrounding an energy source in its centre.

Niven’s Ringworld has provided plenty of inspiration for other creations: The military science fiction first person shooter Halo features a number of ringworlds, each around 10,000km in diameter, and often orbiting another planet. Iain M. Banks also featured the structures in his Culture novels: Orbiting stars and weighing in at around three million kilometres in diameter, they’re still a bit smaller than the original, but still provide plenty of elbow room for their inhabitants.

Image: Cryonic07

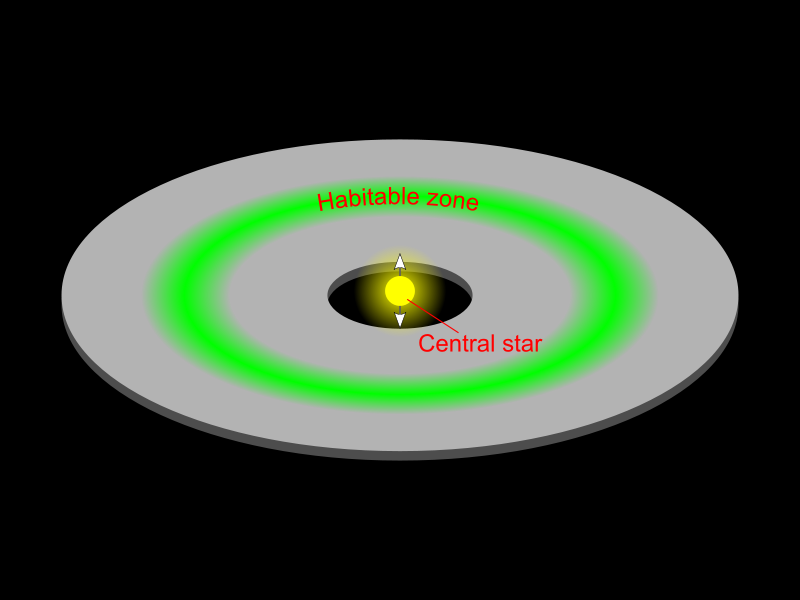

8) Alderson Disk

An Alderson Disk is another ring-shaped structure, but unlike a Ringworld, it looks more like a disk with the sun in the centre. Proposed by Dan Alderson (who wrote some of Voyager 1 and 2’s software), he was a prominent science fiction fan, and came up with the idea of his disk.

A wall would protect the inner part of the disk, holding in the structure’s atmosphere. Unlike a Ringworld, which would maintain a continual habitable region, humans would only be able to inhabit a central band: The areas closest to the sun would be extremely hot, while the areas further away would be extremely cold. Science fiction authors such as Larry Niven, have noted that life could evolve in strange ways, propagating out into the various areas of the disk.

These structures, while arising from science fiction fandom, have only appeared in a handful of stories, most notably the Ultraverse comics and Charles Stross’s novella Missile Gap.

Image: Slawek Wojtowicz

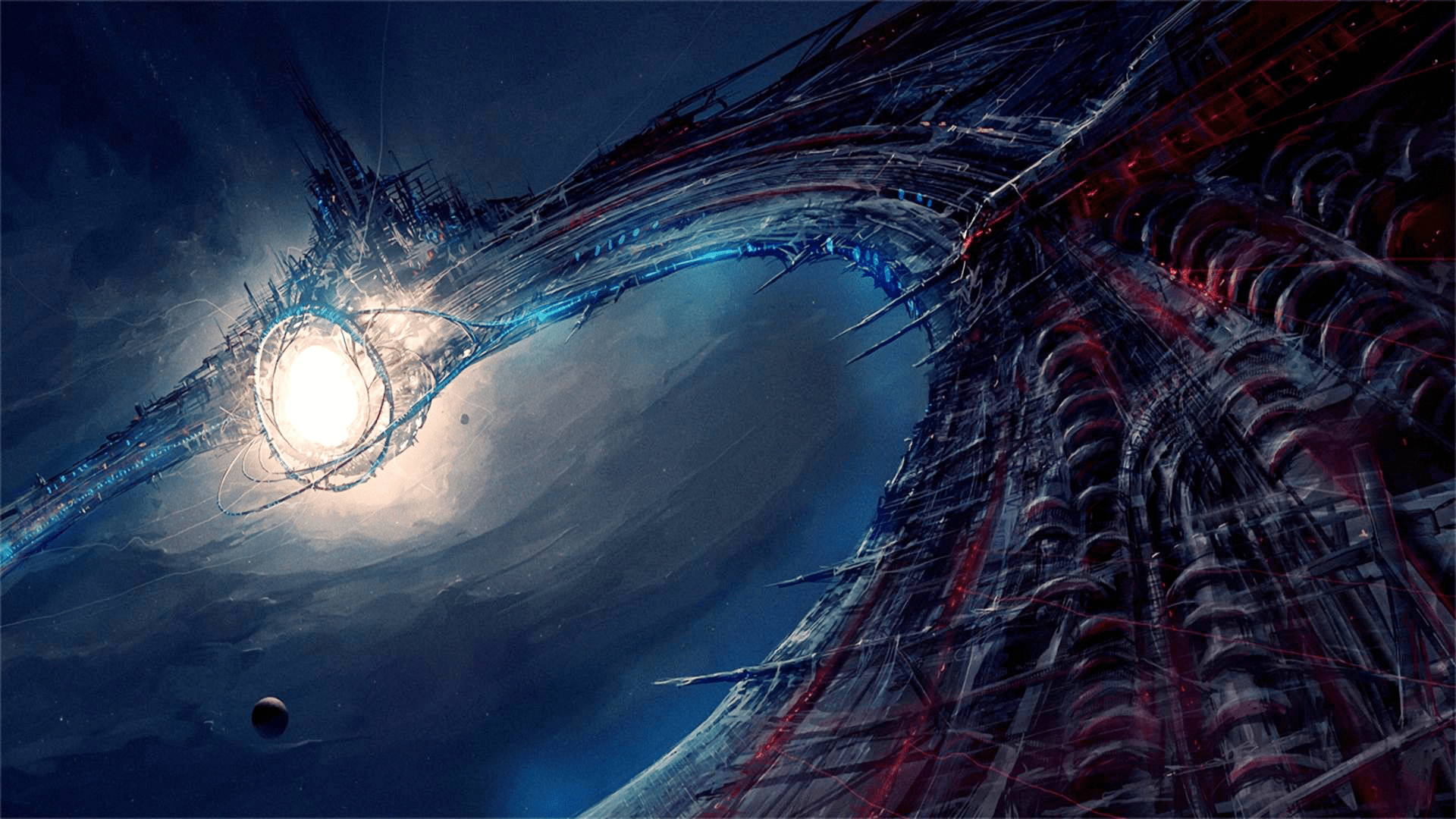

9) Dyson Sphere

Aside from a Ringworld, the Dyson Sphere is one of the more popular types of hypothetical megastructures. Suggested by Olaf Stapledon in his novel The Star Maker and discussed by Freeman Dyson in 1960, a Dyson sphere is a megastructure constructed around a star, to collect the entirety of said star’s output.

As these civilisations grow and become more technologically sophisticated, their energy requirements grow as well. Dyson has noted that this concept doesn’t necessarily require for a star to be completely enclosed: There are other variations, such as a Dyson Swarm or Bubble, which have numerous objects surrounding the star to collect its energy.

Another theoretical structure, a Matrioshka brain, would work within a Dyson sphere: A massive computer system that would utilise the energy of the sun to function, using that energy across multiple layers.

Dyson Spheres are commonplace within science fiction, notably in Star Trek: The Next Generation and in some Star Trek novels, as well as Olaph Stapledon’s Star Maker, Spinneret by Timothy Zahn, Peter F. Hamilton’s Commonwealth Saga and in books by Alastair Reynolds, Stephen Baxter, David Brin, Ann Leckie and Gene Wolfe.

Image: L. Blazkiewicz/CC

10) Shkadov Thruster

First proposed by Dr Leonid Mikhailovich Shkadov during the 38th Congress of the International Astronomical Federation meeting in Brighton, UK in October 1987, the Shkadov Thruster is a stellar engine that utilises the energy of a star for propulsion.

The structure would be a massive solar sail that would direct energy and radiation away from a star, which would drag the star and its planets in one direction. The system shares some similarities with a Dyson Sphere, and anyone looking to move their star system would have to be working on incredibly long time scales: Millions and billions of years.

Olaf Stapledon’s novel Star Maker alludes to stellar engines, while in Larry Niven’s Ringworld, the Puppeteers have embarked on a major project to move five planets out away from the galactic centre.