Say hello to the “Echo Hunter”, a 27 million-year-old toothed whale that’s helping scientists understand how these ancient sea creatures evolved the ability to hear high-frequencies underwater, and then turn that ability into a killing technique.

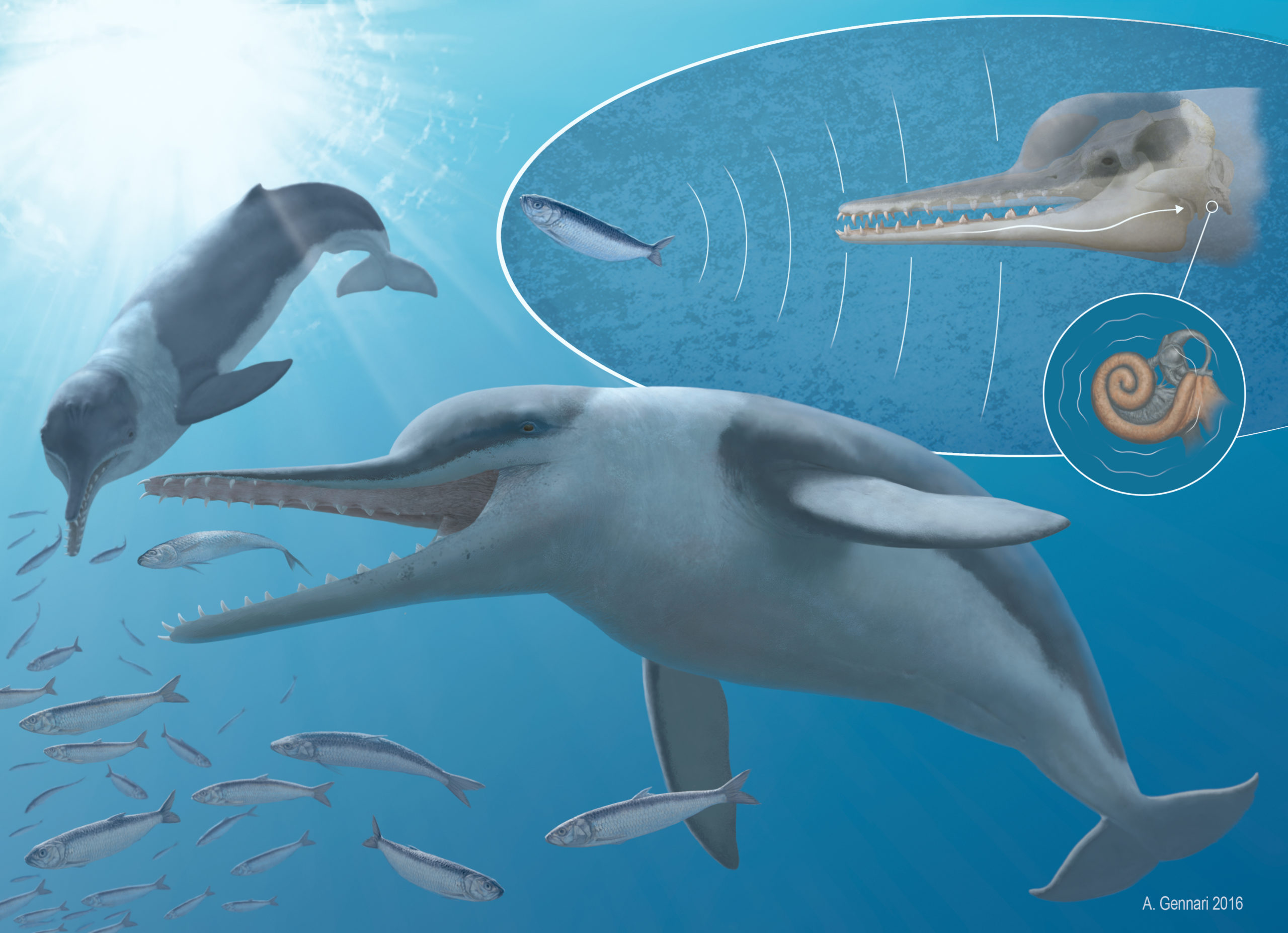

Artist’s depiction of Echovenator sandersi. (Image: A. Gennari, 2016)

In a new paper published in Current Biology, researchers from the New York Institute of Technology and the National Museum of National History in France describe a new species of whale, called Echovenator sandersi (meaning “echo hunter”), that’s providing important new clues about the evolution of high-frequency hearing in aquatic mammals. This research pushes the origin of ultrasonic hearing in whales about 10 million years earlier than previous estimates.

E. sandersi was an ancient relative of the dolphin, and it could hear frequencies well above the range of human hearing. A team led by NYIT professor Morgan Churchill came to this conclusion after analysing a 27 million-year-old skull that was discovered in a South Carolina drainage ditch in 2001. Analysis of the bony support structures in its inner ear membranes, along with other measurements of the inner ear, indicate that this ancient sea creature had ultrasonic hearing capabilities.

After analysing the fossilised ear with a CT scanner, the researchers compared it to those of two hippos and 23 known cetaceans. They uncovered several features also found in modern dolphins, which can hear at ultrasonic frequencies. These whales were able to detect high-frequency echoes by sensing vibrations first through the mandible, and then in the inner ear. In fact, these hearing organs were so well defined, and so modern, that the researchers suspect ultrasonic hearing emerged even earlier than 27 million years ago.

As a hunting technique, echolocation requires two things to work. First, an animal — whether it be a bat, a dolphin, or a whale — needs to be able to hear high-frequencies. Secondly, it requires the ability to produce a high frequency sound, and then interpret those reflections to pinpoint the exact location of prey. “Our study suggests that high-frequency hearing may have preceded the emergence of echolocation,” noted Churchill. What’s more, the discovery of E. sandersi suggests both of these capacities existed at least 27 million years ago.

“This was a small, toothed whale that probably used its remarkable sense of hearing to find and pursue fish with echoes only,” noted study co-author Jonathan Geisler in a statement. “This would allow it to hunt at night, but more importantly, it could hunt at great depths in darkness, or in very sediment-choked environments.”

Looking ahead, the researchers would like to study the skull in more detail to figure out which features of the inner ear are required to hear sounds of a given frequency.