Until the day he died, physicist Samuel Cohen declared that his invention, the neutron bomb, was a “moral” and “sane” weapon that would kill enemy combatants, while sparing civilians and cities. But, despite the support of fans like Ronald Reagan, this weapon of not-as-much mass destruction proved to be a hard sell.

Although Samuel Cohen never achieved the fame of Robert Oppenheimer and Edward Teller, he had been part of the U.S. nuclear weapons program from its very inception. He had worked on the Manhattan Project, where he performed calculations related to the atomic bomb’s yield of neutrons. After the war, he was a consultant at the Rand Corporation.

According to his memoir, Shame: Confessions of the Father of the Neutron Bomb, he hit upon his idea during a 1951 visit to Seoul, where he witnessed the devastation of the Korean War: “The question I asked of myself was something like: If we’re going to go on fighting these damned fool wars in the future, shelling and bombing cities to smithereens and wrecking the lives of their surviving inhabitants, might there be some kind of nuclear weapon that could avoid all this?”

A Kinder, Gentler Nuke

Cohen’s invention was, essentially, a smaller, “fun-sized” version of a hydrogen bomb with a few simple modifications under the hood.

Since a hydrogen bomb utilises fusion as well as fission, it releases much more of its energy in the form of prompt radiation — especially neutrons — than a fission bomb does. Most of those neutrons, however, are absorbed by a “jacket” of uranium-238 that encases the fusion-fission device, in order to further increase the explosive yield of the bomb.

A neutron bomb is a hydrogen bomb without the uranium-238. This lowers the explosive yield while letting the neutrons bust out all over.

So, when a fission bomb explodes, the released energy is distributed as:

- 50% blast

- 35% thermal radiation (heat)

- 10% residual radiation (fallout)

- 5 % prompt radiation (gamma rays, neutrons, X-rays)

Cohen believed that he could increase the output of prompt radiation to as high as 80%, while scaling back on the amount of energy released in the form of blast, heat and fallout.

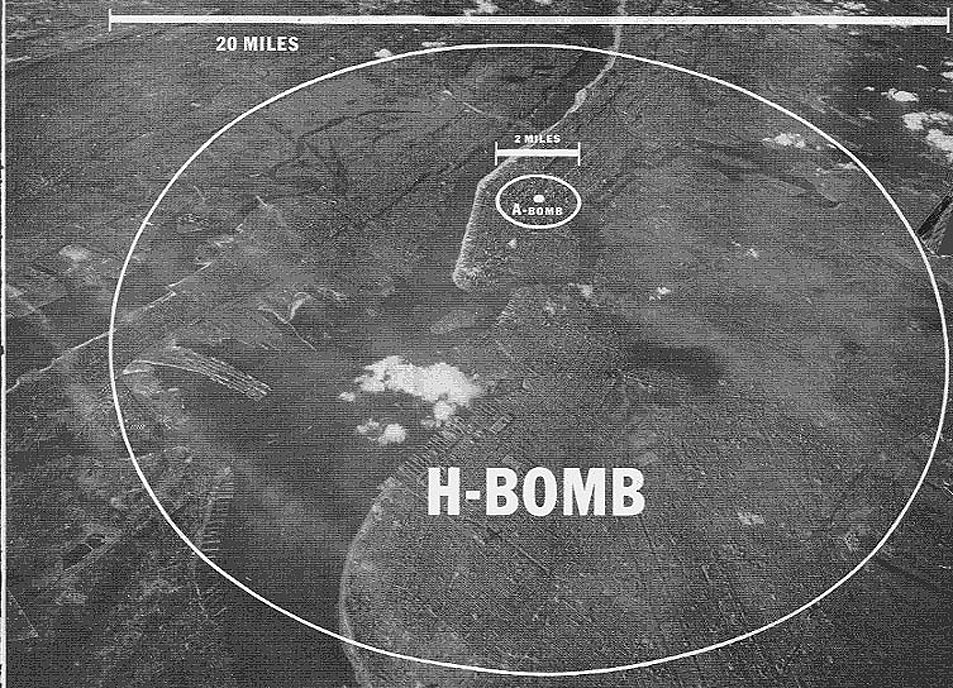

As such, the neutron bomb would provide less bang for the buck. It would be a tactical nuke, explicitly used to kill enemy combatants on the battlefield while, supposedly, minimising the amount of physical collateral damage. The official name for the bomb was an “Enhanced Radiation Weapon” (ERW).

In order to be effective militarily, a neutron bomb would have to incapacitate its victims quickly. This requires a very high dose, in the neighbourhood of 8,000 rems. For a one-kiloton ERW detonated at 457.20m, the required lethal dose would cover an area of about 0.8 square miles. Anyone in this kill zone would die in a particularly gruesome manner, as neutrons collided with protons inside living tissue. The ionization would break down chromosomes, cause nuclei to swell and destroy all types of cells, especially those in the central nervous system.

A Political Explosion

Cohen and his colleagues at the nuclear weapons labs spent years lobbying government and military officials to develop the neutron bomb, arguing that it was a more discriminating weapon with both moral and military advantages.

Finally, they found support from President Richard Nixon’s Secretary of Defence James Schlesinger, who was seeking the capability to conduct limited nuclear warfare “so that if deterrence were to fail…the use of nuclear weapons would not result in [an] orgy of destruction.” This might be possible, he believed, through the use of “a sufficient accuracy-yield combination to destroy only the intended target and to avoid widespread collateral damage.”

The neutron bomb offered Schlesinger what he wanted. He remained the Secretary of Defence after Nixon’s resignation and, in 1975, the Ford administration authorised development of the weapon, which would be overseen by the Energy Research and Development Administration (ERDA). The neutron bomb would be designed for tactical use to offset the Warsaw Pact’s three-to-one advantage in tank forces. The army requested neutron warheads for its Lance short-to-medium-range tactical missile and its 20cm and 155 mm artillery pieces.

But, it was President Jimmy Carter who would inherit the program and make the final decision about deployment. There was just one small problem: nobody had bothered to tell Carter that the weapon was being built. The president found out about it the same way as the rest of the world….he read about it in the Washington Post.

Reporter Walter Pincus had learned about the neutron bomb when he saw a congressional committee report that included testimony about its development. On June 6, 1977, he published an article with the dramatic headline, “Neutron Killer Warhead Buried in ERDA Budget.” The article described the weapon as “specifically designed to kill people through the release of neutrons rather than to destroy military installations through heat and blast.”

Most of the Carter administration had not been aware of the neutron bomb project. Those who had known about, including Secretary of Defence Harold Brown and James Schlesinger (who was now the Secretary of Energy), never imagined that it would be controversial.

Carter’s aides knew differently — not least, because the president had made it a point to pledge in his inaugural address, “we will move this year a step toward our ultimate goal — the elimination of all nuclear weapons from this Earth.”

Domestic critics saw the neutron bomb as an escalation of the arms race. Others charged that, by making nuclear weapons less destructive, it made nuclear war easier to wage. Leftists even called it a “capitalist” bomb because it killed people while protecting property.

But criticism in the U.S. was calm compared to the backlash in Europe. The neutron bomb wasn’t a strategic weapon to serve as a deterrent; it was a tactical weapon intended for actual use on the battlefield — and that battlefield happened to be located on European soil.

Ironically, the supporters of the bomb had thought that it would ease European fears, by promising a technological breakthrough that would limit the worst effects of nuclear war. Instead it had the opposite effect and served as a rallying issue for Europe’s growing anti-nuclear weapon movement, which had become increasingly convinced that the nuclear powers, despite their lip service to work toward disarmament, would continue to expand and modernise their arsenals.

The extent of the opposition across Europe was stunning. A “Halt the Neutron Bomb” campaign in the Netherlands brought out 50,000 protesters, and delivered a petition to the Dutch parliament signed by 1.2 million. Polls in the UK found that 72% of voters who had heard of the neutron bomb opposed its deployment.

But, while there was widespread grassroots opposition, some European governments felt differently. On July 22, 1977, National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski told Carter that, although NATO officials wanted the new weapon, “they are terrified by the political consequences of seeming to approve nuclear warfare on their territory and endorsing a weapon which seems to have acquired a particularly odious image.”

Brzezinski later organised a compromise strategy: the U.S. announced that it would be willing to forego deployment if the Soviet Union, in turn, would forego deployment of its SS-20 intermediate range ballistic missile, and NATO publicly approved the plan.

But then, without any warning, in April 1978, Carter announced that he was deferring production of the neutron bomb — a position that meant, in effect, he was cancelling the program. The president had privately reached the conclusion that European governments would be unable to muster support. Carter told his advisors “that the burden and political liability for this weapon, which as far as he could see nobody wanted, was being placed on his shoulders instead of being shared by the whole alliance.”

Carter’s surprise decision frustrated European leaders who had spent political capital to support the deployment of a weapons system that would not be produced. The administration was widely criticised domestically for its handling of the entire affair. The Washington Post ran a cartoon depicting the president as an out-of-control missile. The caption read: “It’s the Cartron bomb — it knocks down supporters without damaging opponents.”

Reagan’s Raygun

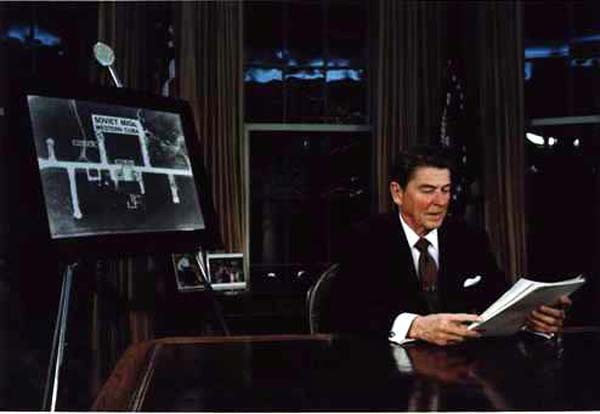

Ronald Reagan also criticised Carter’s decision to halt production of the neutron bomb. He was excited about its potential, saying that:

“Very simply, it is the dreamed of death ray weapon of science fiction. It kills enemy soldiers but doesn’t blow up the surrounding countryside or destroy villages, towns and cities…..Here is a deterrent weapon available to us at much lower cost than trying to match the enemy gun for gun, tank for tank, plane for plane.”

After Reagan was elected president, he announced that he was reviving the neutron bomb program. But, in Europe, opposition against deploying the weapon had hardened even further.

Security experts openly warned against the potential consequences of using the neutron bomb. Some were convinced that, if the U.S. used tactical nuclear weapons, the Soviet Union would escalate the conflict and respond with strategic nuclear weapons.

Admiral Lord Hill-Norton, a former Chairman of the Military Committee of NATO wrote in The Times on August 18, 1980:

“Once you cross the nuclear threshold you have taken an irreversible step which is almost bound to lead to a strategic nuclear exchange, which in turn is almost bound to lead to the end of civilisation…I will go to my grave being certain that if you let off a neutron bomb anywhere in Europe you have gone 90% of the way toward triggering a strategic nuclear exchange.”

Another concern was that the decision to use the weapon would be placed in the hands of field officers. Brigadier Michael Harbottle, a retired British army officer, wrote in 1981 that:

“Because it is a close combat weapon with an immediate response capability, the decision to use it is likely to be delegated to the tactical field commander at the point of attack. The decision to fire will be tactical not strategic, and is unlikely to take into account the wider repercussions.”

And then, there was the claim that civilians would be spared from the “collateral” effects of the weapon. Although the “kill zone” was, in theory, limited to 0.8 square miles, there was also a considerably larger area (about 2.5 square miles) within which the dose, though not enough to incapacitate quickly, could still cause radiation sickness. Hence, 2.5 square miles would need to be considered the lethal area of the weapon as far as civilians were concerned.

That posed a big problem, since Western Europe was such a densely populated region. In Germany, the average distance between populated places was only a little over a mile, so there were simply not many areas in the prospective battle zone where 2.5 square miles would not contain substantial numbers of noncombatants.

Indeed, a large-scale Warsaw Pact invasion would have involved something like 20,000 tanks. And those tanks would not be conveniently deployed in closely-packed formations. Surveillance of Warsaw Pact field exercises suggested that no more than 10 to 20 tanks would likely be within the effective area of a single weapon. Western forces, therefore, would have to detonate hundreds of neutron bombs.

And, finally, the ultimate kicker. The warheads being built by the U.S. had not achieved the efficiency that physicist Samuel Cohen had envisioned decades earlier. They didn’t yield 80% neutron radiation, but only 30%, while the blast and thermal energy yields had been reduced only marginally, to 40% and 25%. Under those circumstances, it was viewed as folly to believe that Western forces could minimise collateral physical damage in Europe.

Confronted with European refusal to allow deployment of the weapons, the bombs never left the U.S. and were dismantled during the first Bush administration. As precision-guided weaponry continued to mature and become more sophisticated, the rationale for building a neutron bomb faded.

Samuel Cohen never forgave Ronald Reagan for what he deemed was a betrayal against him and his country. In 2006, the embittered physicist completed the third revision of his memoirs and published them for free on the Internet. This edition of the book had a new title: Fuck You! Mr. President.