Though over 1 billion people suffer from them, they’re called “neglected diseases.” That’s because they attract little public attention and research money. But these diseases are about to explode across the globe, which is why many doctors say the neglect needs to stop now.

Illustration by Jim Cooke.

It’s a safe bet you’ve heard of malaria, HIV, tuberculosis, and ebola. But how about blinding trachoma, schistosomiasis, or chagas disease? Probably not so much. That’s because they’re neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) — parasites, viruses, and other blights that are not widely known, understood, or researched. The vast majority of NTDs are tropical, affecting mostly poor populations in rural sub-Saharan Africa. But it’s a problem with global reach — one that’s set to spread as climate change expands the range of tropical afflictions, and as our civilisation becomes increasingly interconnected.

NTDs afflict more than 1.4 billion people worldwide, many of whom live on less than $US1.25 ($2) per day. They include some of the most common infections in the developing world, and account for the leading causes of chronic disability in low- and middle-class countries. These diseases are not limited to impoverished tropical regions; several are, or were once, endemic in the United States, southern Europe, and Turkey.

NTD: Trichuriasis (Stanford University)

NTDs don’t attract a lot of public, corporate, academic, and media attention, but they cause serious health problems and significant economic burdens. In addition to causing hundreds of thousands of deaths each year, they can result in blindness, serious digestive issues, stunted growth, anemia, cognitive impairments, and complications with pregnancies. Compounding the problem is the disturbing fact that many people often suffer from two or more of these diseases at the same time.

Earlier this year, Bill Gates put it well when he said: “If this was one disease and the entire burden was attributed to one disease, it would be right up there with the big diseases. As a group … the human burden [in terms of disability] is pretty gigantic.”

Indeed, it’s a serious public health concern — one that needs the world’s attention and some thoughtful solutions.

Under the Radar

According to the World Health Organisation, neglected tropical diseases result from four different causative pathogens: viruses, protozoa (single celled eukaryotic organisms), helminth (parasitic worms), and bacteria. The WHO has prioritised 17 particular NTDs, a group of infections found in 149 countries. They are:

- Viruses: Dengue Fever, Rabies

- Protozoans: Chagas disease, Human African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness), Leishmaniases

- Helminth: Cysticercosis/Taeniasis, Dracunculiasis (guinea-worm disease), Echinococcosis, Foodborne trematodiases, Lymphatic filariasis, Onchocerciasis (river blindness), Schistosomiasis, Soil-transmitted helminthiases

- Bacteria: Buruli ulcer, Leprosy (Hansen disease), Trachoma, Yaws

Other neglected conditions include: Chronic suppurative otitis media (CSOM), Mycetoma, Nodding Syndrome (NS), Podoconiosis, Scabies, Snakebite, and Strongyloidiasis.

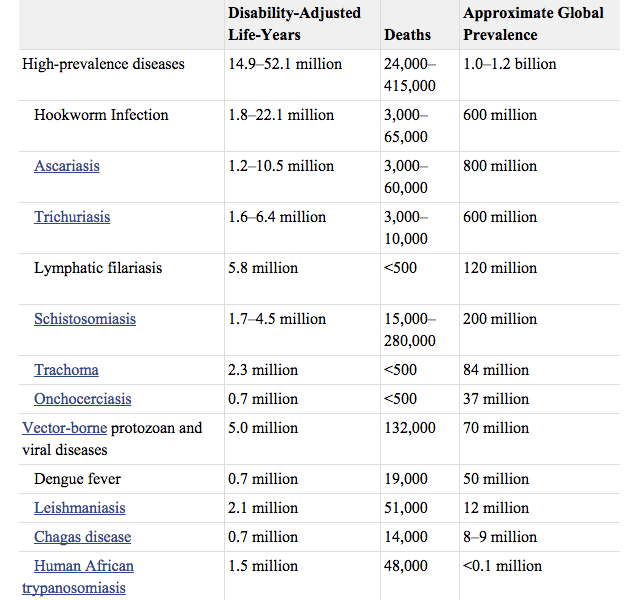

A recent study on NTDs listed these seven as the most common neglected tropical diseases:

Ascariasis

This is the most common of the soil helminth diseases, affecting one billion people worldwide. These large worms (up to 10cm in length) can wreak havoc on the intestines, especially when they grow in number. This can lead to severe malnutrition in children, resulting in downstream deficits in learning at a critical developmental age. Like all soil helminths, these parasitic worms live in soil that is contaminated with human excrement. Oftentimes the same drugs are used to treat all three responsible parasites, which often infects the same individuals at the same time. All thrive in the human intestine, and mainly cause severe malnutrition in children, though there are subtle details to how symptoms develop.

Hookworm infection

Hookworm affects 650 million people, and unlike ascariasis, it can be transmitted through the skin — a person doesn’t need to eat contaminated food to contract it, but by simply walking on contaminated soil. It also affects the intestines, but because the parasites are small, the symptoms arise from their voracious appetite for blood, leading to anemia.

Trichuriasis

Another soil helminth disease, it affects 700 million people. The parasites are not as large as ascaris, but not as small as hookworms, and symptoms occur when the parasites damage the intestinal wall, leading to malnutrition.

Schistosomiasis

Yet another parasitic worm disease, but transmission occurs through contact with freshwater that is contaminated by snails harboring the parasites. The parasites reproduce in the human body and in the snails, causing symptoms that affect the skin, the intestines, and the bladder, Some 200 million people suffer from the disease worldwide. This disease is similar to the soil helminths but differs slightly in the life cycle of the parasite and the human organs it affects. However it is often grouped with the soil helminths because of its prevalence, and because a lack of toilets is a primary contributor to the creation of infectious environments in all four cases.

Unfun fact: in ancient Egypt, and in some regions up until the early 20th century, the bloody urine caused by schistosomiasis was considered to be the male equivalent of menstruation, and thus became a proxy rite of passage for young boys.

Lymphatic filariasi

This is an infection of the lymph nodes by roundworms that are transmitted by mosquito bites. Around 120 million people suffer from the disease, which causes swelling of lymph nodes and other organs that can lead to elephantiasis, permanent disability, and ostracization.

Onchocerciasis

Onchocerciasis is a skin disease caused by roundworms that are transmitted by black flies, which live near water and can bite humans. In severe cases, the dead or dying larvae can damage or even blind the eyes, giving this disease the name “river blindness.” Of the 37 million people who are infected, 300,000 are permanently blind. Like lymphatic filariasis, it’s transmitted by insect vectors, making prevention of bug bites paramount for prevention of these diseases. Each causes disability in severe cases.

Trachoma

Trachoma is the leading cause of preventable blindness worldwide, completely blinding 1.2 million people, and partially blinding an additional million, out of 80 million infected individuals worldwide. It is caused by a bacterium that is transmitted through direct contact with either an infected person or flies that have landed on that person. Good facial hygiene in children is particularly important for prevention. This is the only bacterial disease on this list, and it resembles diseases we are more familiar with for that reason. Still, hygiene and sanitation would go a long way towards preventing trachoma, which blinds many of its victims, making it particularly worrisome in spite of the overall lower numbers of infected individuals.

High-prevalence and other vector-borne NTDs (via Hotez et al. 2009).

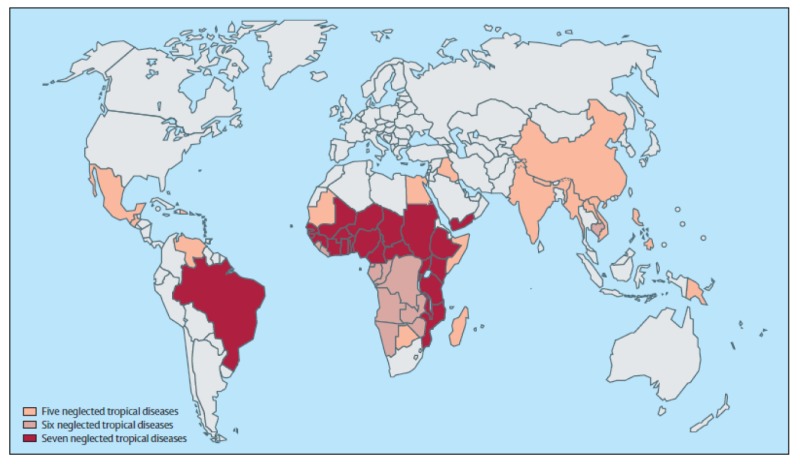

Geographical overlap and distribution of the seven most common neglected tropical diseases: ascariasis, hookworm infection, trichuriasis, schistosomiasis, lymphatic filariasis, onchocerciasis, and trachoma (via Hotez et al. 2009).

The Blame Game

There are many reasons why certain diseases remain neglected.

The public’s attention tends to gravitate towards some of the most sensational and overtly horrific diseases. Ebola is a perfect example. NTDs rarely cause explosive outbreaks, which tends to draw attention to highly infectious diseases.

Some diseases get all the attention. (Outbreak)

People who live outside of tropical regions don’t tend to feel personally threatened; though these diseases are communicable, they’re not easily exported to developed countries — so they’re not seen as threats. More than that, however, many of us are simply unaware that these diseases even exist.

These diseases also cause high morbidity — which is often difficult to measure — and fewer deaths than HIV/AIDS and malaria; the health effects of NTDs are less apparent.

And as noted by Ezekiel Emanuel of the White House Office of Management and Budget, NTDs are weak as a “brand” when taken individually; most diseases that comprise the NTDs have complex, hard-to-pronounce names.

There’s also much debate as to which diseases deserve to be designated as neglected:

Exactly which diseases are NTDs is another unresolved question — a range of lists were presented at the [2010 NTD] workshop, from the “7 most common and/or most treatable diseases” to a list of 30 “neglected diseases of poverty.” There was considerable controversy as to whether or not dengue is an NTD. Some argued that dengue is an acute emerging febrile illness, rather than a chronic, debilitating disease, and therefore does not fit the NTD model; others contended that dengue and other intermittent, acute diseases — which also include chikungunya and Japanese encephalitis — result in lifetime disability that is indeed neglected. (source: Institute of Medicine, 2010)

One person who has given this subject considerable thought is computational biologist Guido Núñez-Mujica. He’s a researcher at the Engineering School of the University of Development, UDD in Santiago, Chile.

“A disease becomes neglected simply because it does not affect people in developed countries, so it’s not a research priority,” he told io9. “In some cases, like with schistosomiasis, there’s a treatment, and it’s inexpensive, but it’s practically impossible to eradicate the parasite or its vectors because populations live in close contact with them, and many people are infected with other host species, so people get sick again and again.”

In other cases, Núñez-Mujica says there’s no treatment, no vaccines, and no tests to reliably detect the presence of diseases.

“Neglected diseases are often the products of a perfect storm,” he says, “Many of these organisms are very tough to beat, so there are no treatments or vaccines. What’s more, infections can be transmitted via multiple vectors, and with plenty of different hosts living in the wild close to human populations.”

He also says there’s a significant lack of funds for research and a general lack of awareness about these diseases.

“Too often, these diseases affect only the poorest among the poor, in remote isolated areas that local governments pay very little attention too,” he says. “And while many of these diseases kill in dramatic and terrible ways, many others are slow and invisible, so the real magnitude of the problem is hidden.”

Related: China Is Testing An Unproven Malaria Drug On An Entire African Nation

Indeed, lack of awareness is a serious problem — even at the highest levels of decision making.

Back in 2007, for example, the World Health Organisation called for the elimination of Chagas disease by 2010 — a goal Núñez-Mujica describes as being completely absurd and unrealistic.

“The hosts of this blight live by the millions in the forest and jungles of afflicted areas,” he says. “Yet, with no vaccine and no cure, the WHO actually thought it was feasible to eliminate it in just three years.”

Stepping Up

Another person who’s deeply concerned about NTDs is Peter Hotez from the National School of Tropical Medicine at the Texas Children’s Hospital. He’s the founder and editor of PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, a peer-reviewed open access journal dedicated to the topic.

It was established back in 2007 with a US$1.1 million grant from The Gates Foundation. It was created to be “both catalytic and transformative in promoting science, policy, and advocacy for these diseases of the poor.”

Like all other journals of the Public Library of Science, PLoS NTDs charges authors a US$2,200 publication fee, but it waives the fee for authors who don’t have the funds.

As noted, Bill and Melinda Gates are active in this field as well. Through their funding and advocacy efforts, they want to “reduce the burden of neglected infectious diseases on the world’s poorest people through targeted and effective control, elimination, and eradication efforts.” To that end, The Gates Foundation supports efforts to develop new ways to attack multiple infectious diseases simultaneously, and in a coordinated and integrated fashion. They have set aside three main areas of focus:

Mass drug administration: In areas where several infectious diseases are prevalent and can be treated with the same drugs or a similar schedule of drug treatments, we support efforts to coordinate the various components of large-scale drug administration programs, such as obtaining commitments to donate drugs.

Public-health surveillance: In fighting infectious diseases, good data is crucial — such as data on where a disease is prevalent in humans and in the mosquitoes, flies, worms, or other vectors that transmit it. Such data is lacking for many neglected diseases. We are seeking solutions such as shared approaches to sample collection and processing, data aggregation, and the design of efficient surveillance systems.

Vector control: Most neglected infectious diseases are caused or spread by insects or worms, which are costly and difficult to control. But control measures are similar for all of these vectors, so better cross-disease coordination would improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the various vector-control efforts. We support the development of a framework for cross-disease coordination to improve the coverage and impact of vector-control measures.

Bill and Melinda Gates are actively working to help the WHO meet its Millennium Development Goals. With the help of the international community, the WHO hopes to halt and reverse the incidence of malaria and other major diseases by 2015 — including the neglected ones. As the WHO states:

Despite renewed momentum characterised by unprecedented progress, some neglected tropical diseases (like dengue) remain a significant obstacle to health, making it harder to achieve the Millennium Development Goals, and pose an ongoing impediment to poverty reduction and overall socio-economic development.

Encouragingly, there has been some progress. Leprosy has now been eliminated as a public health problem in 119 out of the 122 countries where it was previously endemic, and dracunculiasis (also known as guinea-worm) is on verge of eradication, with only 148 cases reported in 2013.

These measures aside, Núñez-Mujica remains pessimistic.

“Neglected diseases are going to remain neglected for a long time, he told io9. “The resources needed are simply not there, and even with the help of the Gates Foundation and others, it’s simply a problem that very few people care about. And it simply doesn’t offer a lot of potential profit.”

He also says it’s not completely fair to place the blame on Big Pharma.

“We must remember that developing a new drug can cost USD$800 million,” he says. “Funds for research are scarce and often invested in countries believed to be the biggest priorities.”

This will be the reality, he says, for as long as drug development costs remain as expensive as they are now. At the same time, drug development appears to follow an all-too-familiar pattern.

“Diseases have a long tail, with a few of them attacking hundreds of millions of people, while many others afflict lower numbers,” he says. “We are not going to make much progress until we can address that long tail, which will require new methods and an influx of people devoted to different problems.”

Núñez-Mujica says it’s important that we increase the efficiency of our resource use. We need to train local scientists and specialists, develop cheaper hardware and techniques for biological research, much like the DIY Bio movement is doing. Indeed, along with open access journals, such efforts could do much to help afflicted regions help themselves.

In addition, Núñez-Mujica says we also need to increase the amount of research being done in theoretical models of the pathogens and organisms to study possible vulnerabilities and listen to doctors and researchers who have experience working in the endemic areas. And in addition to setting up public policies that minimise the number of new cases, we need to improve epidemiology efforts to monitor and track these and new emergent diseases before we have another situation like the ongoing Ebola outbreak.

Additional reporting by Levi Gadye. Other sources: “The Causes and Impacts of Neglected Tropical and Zoonotic Diseases: Opportunities for Integrated Intervention Strategies” | WHO | Gates Foundation

Follow George Dvorsky on Twitter and friend him on Facebook.

Related: Epidemics Are Not Natural