Scientists are excited about the prospect of using CRISPR, a powerful gene-editing tool, to combat HIV. A discouraging follow-up study shows that HIV is capable of developing a resistance to the genetic attack — but scientists say CRISPR’s battle with HIV is far from over.

To quickly recap, scientists have started to use the CRISPR/cas9 gene-editing system to pluck out viral DNA from HIV-infected T-cells. It may be years before we see this technique used on actual patients, but if it ever reaches the clinical stage, it could eliminate the need for antiretroviral drugs, which are costly and don’t actually cure HIV. Sadly, a new study published in Cell Reports shows just how hard it’s going to be to finally defeat this virus. It turns out that HIV-1 is capable of adapting to CRISPR.

HIV, like all retroviruses, copies its genome into host cells in order to replicate, which is why scientists are so stoked about using CRISPR to fight it. This system can scan an infected strand of DNA, locate the viral parts and strip it out. Over the past several years, nearly a half-dozen papers have been published on the subject, including a recent study conducted by virologist Chen Liang at McGill University in Montreal.

Two weeks after the initial experiment, Liang noticed that his modified T-cells were churning out new copies of HIV-1, a sign that some cells had managed to evade CRISPR’s genetic attack. While single mutations had successfully inhibited viral replication, others actually conferred unexpected resistance. The problem is that HIV is really good at surviving mutations — and it’s really, really good at turning certain mutations into an advantage. This case being no exception.

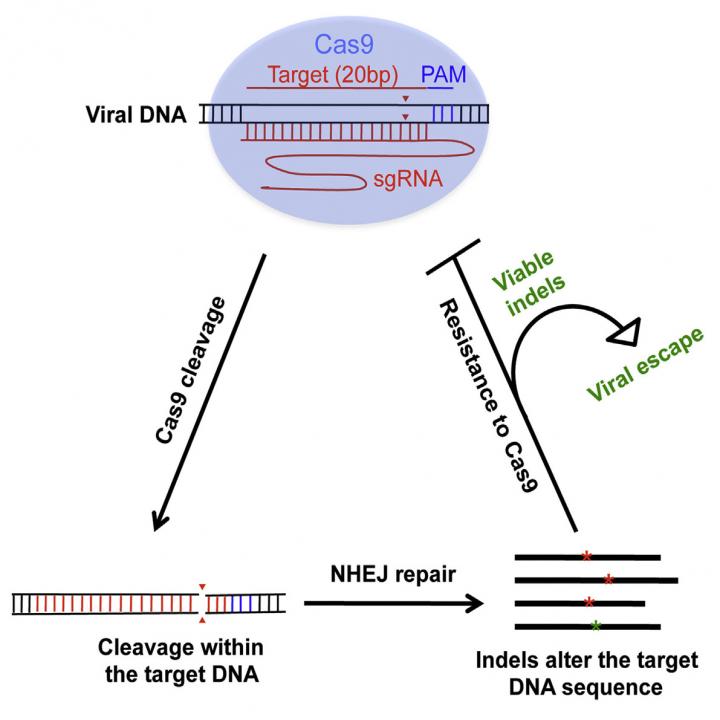

Image: Wang et al./Cell Reports 2016

The clues to the problem lay in Liang’s initial experiment. He used CRISPR to chop-up the viral DNA that had made its way into the host cell. Afterwards, the cell managed to repair the broken part of the genetic sequence, leaving a “scar tissue” that should, in theory, prevent the viral DNA from functioning.

And for the most part, that worked. But in some instances, the scar tissue made the virus stronger (such as the ability to replicate even faster). Not only that, the scar tissue didn’t resemble the old genetic sequence, so the CRISPR/cas9 system couldn’t recognise it anymore, rendering it useless. In essence, HIV developed a kind of immunity to CRISPR.

“Some mutations are tiny — only a single nucleotide — but the mutation changes the sequence so Cas9 cannot recognise it anymore,” said Liang in a statement. “Such mutations do no harm to the virus, so these resistant viruses can still replicate.”

This bit of insight has given the scientists another idea. As Liang told New Scientist, they could still use CRISPR to “carpet bomb” the viral DNA residing in the host cells. “The key could be using multiple viral sites for editing,” Kamel Khalili of Temple University told New Scientist. “This would reduce any chance for virus escape or the emergence of virus resistant to the initial treatment.”

So in the ongoing battle to defeat HIV, don’t count CRISPR out just quite yet.

[Cell Reports via New Scientist]

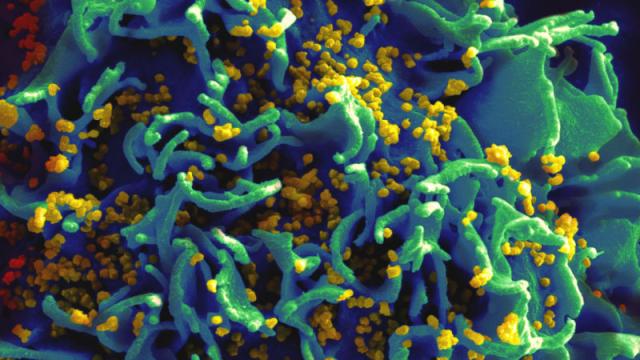

An electron micrograph of HIV particles infecting a human T cell. Image: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases