The Cassini spacecraft made its final close flyby of Saturn’s icy moon Enceladus in December, releasing its final up-close look at these weird little spots last week. Discovered over a decade again, we’re still trying to work out exactly how these spots formed.

Now the spacecraft is making its farewell tour of Saturn’s moons in preparation for a final big dive in between the rings before crashing into the gas giant.

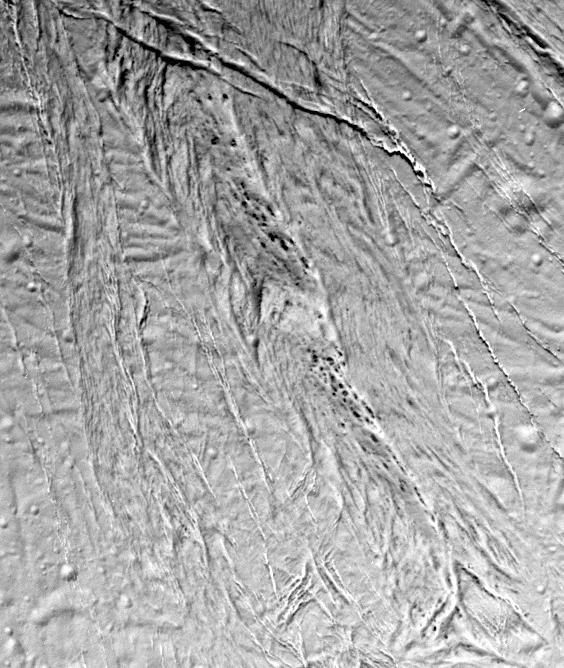

The small dots were first spotted during a flyby in 2005 in the “smooth plain” region of the little moon, facing Saturn and just north of the equator. The tiny black pits posed a new mystery.

A section of Enceladus in the “smooth plains” region slightly north of the equator on the Saturn-facing side as seen on 17 February 2005 at 125m per pixel. North is at an angle to the lower left. Image credit: NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute

The spots aren’t really that little. They range anywhere from 125-750m in diameter. Their distribution doesn’t appear random; instead, rough chains run parallel to narrow fractures. The extreme contrast is especially puzzling, suggesting they might even be compositionally different than the rest of the landscape.

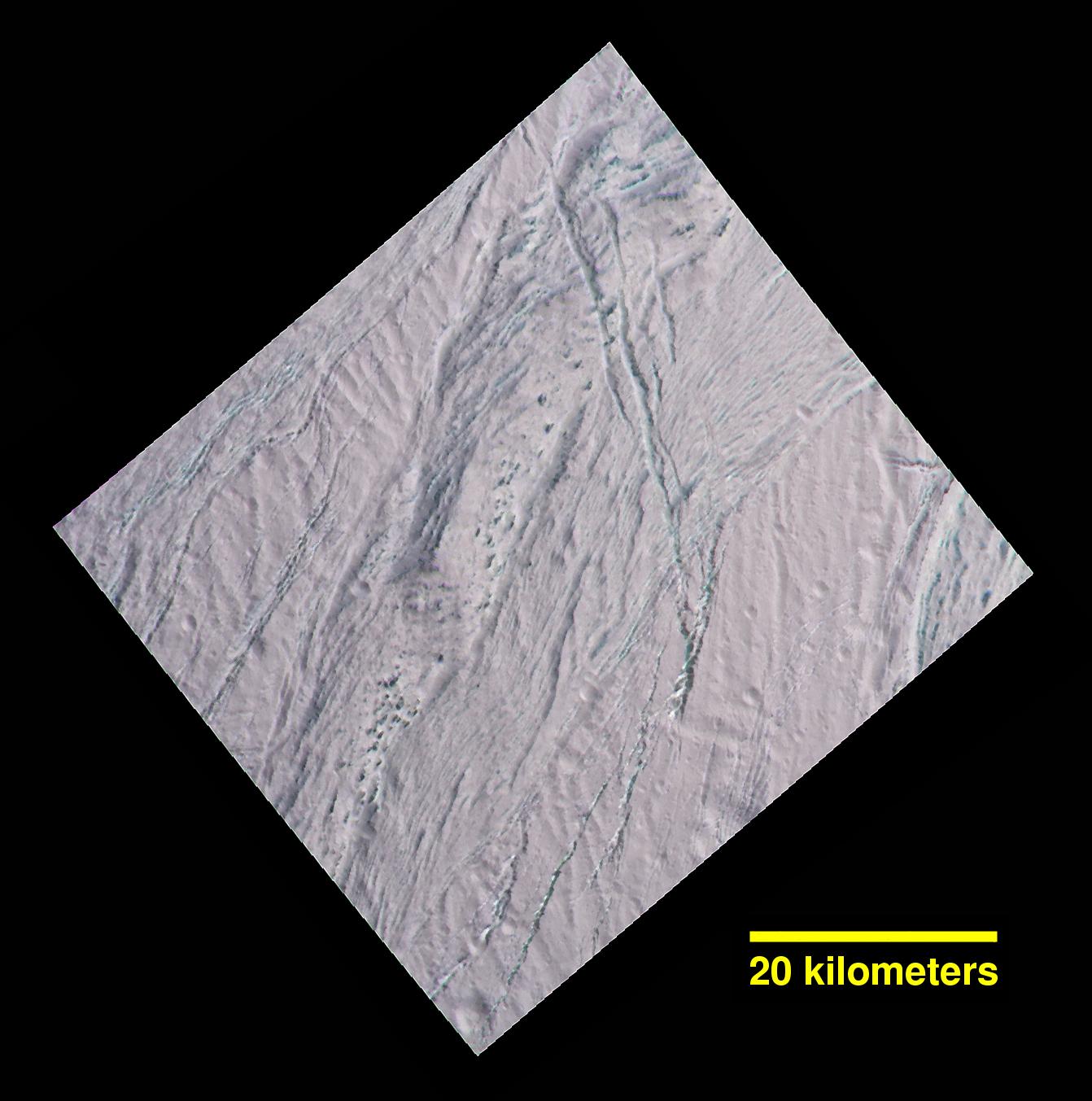

Finally, last week we went back to look again. This time instead of just focusing on optical wavelengths, Cassini imaged the area at higher resolution and included ultraviolet and infrared wavelengths.

A closer look at the “smooth plains” taken on 19 December 2015 at 67m per pixel. North is up. Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute

These new images reveal details the science team couldn’t see before. They’re actually bumps piercing the surface, possibly protruding outcrops of “bedrock” ice or ice blocks. They’re also smaller than initial estimates — tens to hundreds of metres in size.

Scientists don’t yet know how the icy blocks came to be exposed. The moon doesn’t have a thick atmosphere, so it lacks the wind that scours clear surfaces here on Earth. Instead, the blocks might have been cleared by sublimating ice evaporating directly from solid to gas or by tumbling themselves clean while inching downslope.

To visualise wavelengths beyond what we can perceive with our limited human eyes, the image colours are remapped so that ultraviolet (338 nanometres) is blue, green optical light (568 nanometres) is green, and near infrared is red (930 nanometres). Other times we’ve used this colour mapping, all the green bits were coarse grained or solid ice. The same is true here: coarser ice lining the steep walls of cracks and troughs.

It’s a beautiful final view of the moon — and delightfully detailed — that provides new observations for researchers to puzzle over in the future. But it hurts, somehow, knowing that something is weird on Enceladus and we won’t have the tools to keep looking.