The onset of World War I and the current climate change crisis have a lot more in common than you might think. Here’s why the two historical events are eerily similar — and why it’s so damn hard for us to prevent a self-inflicted disaster that everyone knows is coming.

Shortly before he died in 1898, Germany’s great statesman, Otto von Bismarck, prophesied, “One day the great European War will come out of some damned foolish thing in the Balkans.” That “damned foolish thing” turned out to be the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand — but the fateful event was merely the catalyst. The clouds of war had been gathering on the horizon for decades.

Bismarck’s remarkable prediction wasn’t born from thin air. Like many of his contemporaries at the turn of the century, he wasn’t wondering if a war would happen, but rather when. To say that the political and military elite didn’t see the war coming is a myth. Yet, despite the slew of prognostications and warnings, Europe still “slithered over the brink into the boiling cauldron of war”, as the Prime Minister of Britain David Lloyd George later put it.

The outbreak of war in 1914 interrupted nearly a century of relative peace and prosperity in Europe. The continental powers went to war in brazen defiance of the consequences — but the costly, four-and-half-year conflict could have been avoided. As historian Margaret MacMillan writes in The War that Ended Peace:

Very little in history is inevitable. Europe did not have to go to war in 1914; a general war could have been avoided up to the last moment on August 4 when the British finally decided to come in.

So what happened? And why were the leaders of Europe unable to prevent one of humanity’s greatest self-inflicted catastrophes? As we head deeper into the 21st Century, and as we evaluate our pathetic response to the ongoing climate crisis, it’s an episode that’s certainly worth revisiting. Our institutions, it would appear, don’t fare well when a catastrophe is looming.

Warning Signs

As noted by historian Hew Strachan in The First World War, “The literature of warning, both popular and professional, was abundant.” He says the idea that a general war in Europe would not spread beyond the continent was “a later construct,” the product of historical re-interpretation and political convenience.

Similarly, Margaret MacMillan admits the outbreak of war was a shock, but it didn’t come out of nowhere: “The clouds had been gathering in the previous two decades and many Europeans were uneasily aware of that fact.”

Like the current impacts of climate change on Earth, the signs were all there.

“Woe to the country that has a child for a king.” A bombastic portrait of Germany’s Kaiser Wilhelm II in 1890.

The rise of the German Empire in the wake of the Franco-Prussian War (1870-71) did much to alter the geopolitical complexion of Europe, and the world for that matter. Almost overnight, a new great power had appeared. Its founding statesman, Chancellor Bismarck, worked hard to maintain the Concert of Europe — a post-Napoleonic system that managed to maintain the balance of power through treaties, complex alliances, and emergency conferences.

This system, launched at the 1815 Congress of Vienna, had worked remarkably well for decades, but Kaiser Wilhelm II, who inherited the German throne in 1888, had different ideas. For the next quarter century, Wilhelm steered Germany down a hawkish and ambitious path — one that placed it at odds with Britain, France, Russia, and the United States, while bringing it closer to the ailing Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Looking for its own “place in the Sun”, the newly minted German Empire embarked on a policy of Weltpolitik, or “World politics” — a term that gave rise to the troubling possibility of Weltkrieg, or “World War”. Like “global warming” and “superstorms”, Weltkrieg quickly became a popular term with startling relevance.

This Punch comic from 1892 chronicles the resignation of Otto von Bismarck. The old Chancellor is being pushed aside by the new Kaiser to make room for “Weltpolitik”.

It was becoming increasingly obvious to the European powers that, with their complex web of alliances, vast assemblage of colonies, and the mounting need to protect critical sea routes, they might collectively enter into a massive war. The seemingly endless string of international crises from 1870 to 1914 were like the melting polar ice caps — a warning sign that things were not right. As time passed, and as these crises escalated in severity, the sense of fatalism increased.

The deteriorating international scene was also the function of broader changes to the political and social realm. Europe was becoming more diverse, nationalistic, and militaristic. The balances of power, which had up until the start of WWI kept the fragile peace together, were starting to shift. The Concert of Europe was unravelling.

Likewise, our world today is in the process of unravelling, though on an environmental scale. It’s becoming increasingly obvious that our planet, like Europe at the turn of the century, is sick. Our biosphere is currently in the midst of a sixth mass extinction, in which the loss of species is a hundred times greater than expected. The polar ice caps are melting, instigating concerns of rising sea levels, disturbed ocean currents, and the onset of severe weather. Droughts are occurring with increased frequency, causing scientists to worry about protracted “megadrought” episodes.

War is Coming, and it’s Going to Be Hell

It was also clear from the professional and popular writings of the day that Europe was running the risk of entering into a global war — and that, given the new industrial might of nations, it would be a horrible, protracted ordeal. Much of this literature was ignored. As noted by Hew Strachan, the problem was that “hope prevailed over realism.”

Of all the speculative conceptions of future combat that were published, none were as spot-on as the six-volume masterwork, Budushchaya Voina (translated to English as Is War Now Impossible?) by Polish banker and railway financier Jan Gotlib Bloch.

For Jan Gotlib Bloch, the future of war was crystal clear — and terrifying. (Credit: Wyborcza/Archiwum)

Looking at the changes to warfare, and the new tactical, strategic, and political realities, he argued that new weapons technology meant that open ground maneuvers were now obsolete. He calculated that entrenched soldiers on the defensive would have a fourfold advantage over attacking infantry on open ground. He also predicted that industrial societies would enter into a stalemate by committing armies that numbered in the millions, and that large-scale wars would not be short affairs. It would become a siege battle of industrial might and total economic attrition. Grimly, he warned that economic and social pressures would result in food shortages, disease, the “break-up of the whole social organisation”, and revolutions caused by social unrest.

“They [Britain and Germany] had not stayed to consider that a war in Europe, with its manifold intricate relations with the new countries over the seas, the millions of whose populations obeyed a handful of white men, but grudgingly, must necessarily set the whole world ablaze.” F. H. Grautoff (1906)

With hindsight, Bloch’s predictions are eerily prescient. But his contemporaries would have none of it. As MacMillan writes, “Europe’s military planners dismissed his work”, because “after all, as a Jew by birth, a banker, and a pacifist he was everything they tended to dislike”. Moreover, most military and political leaders, who were guided by the popular Social Darwinism of the time, couldn’t fathom a world without national, ethnic struggle.

After reading Bloch’s work, a leading military historian, Hans Delbruck, wrote:

From a scientific standpoint the work does not have much to recommend it. It is a rather uncritical and poorly arranged collection of material; and although it is embellished with illustrations, the treatment is amateurist with vast amounts of detail that have nothing to do with the actual problem.

Seems like the early 20th century had its fair share of sceptics. Today’s climate change deniers are also discounting the advice of experts, and by doing so, are negatively influencing the discussion and stalling meaningful attempts to address the problem.

Fictional accounts of modern, global war were also popular at the turn of the century. During the 1870s and up until the outbreak of the Great War, a genre of fiction known as “Invasion Literature” was all the rage.

The Germans are coming! The Germans are coming! An illustration from George Chesney’s fictional short story, The Battle of Dorking (1871)

It all got started in 1871 with George T. Chesney’s short story, The Battle of Dorking — a fictional account of a German invasion of Britain. It kickstarted a literary craze that tapped into popular fears and anxieties of foreign invasion. By 1914, some 400 books were written in the genre, including H. G. Well’s 1907 novel, The War in the Air, a cautionary tale in which a German invasion of the US triggered a global chain of attacks and counterattacks, culminating in the destruction of all major cities, the collapse of all fighting nations and the global economy, and the onset of a new dark age.

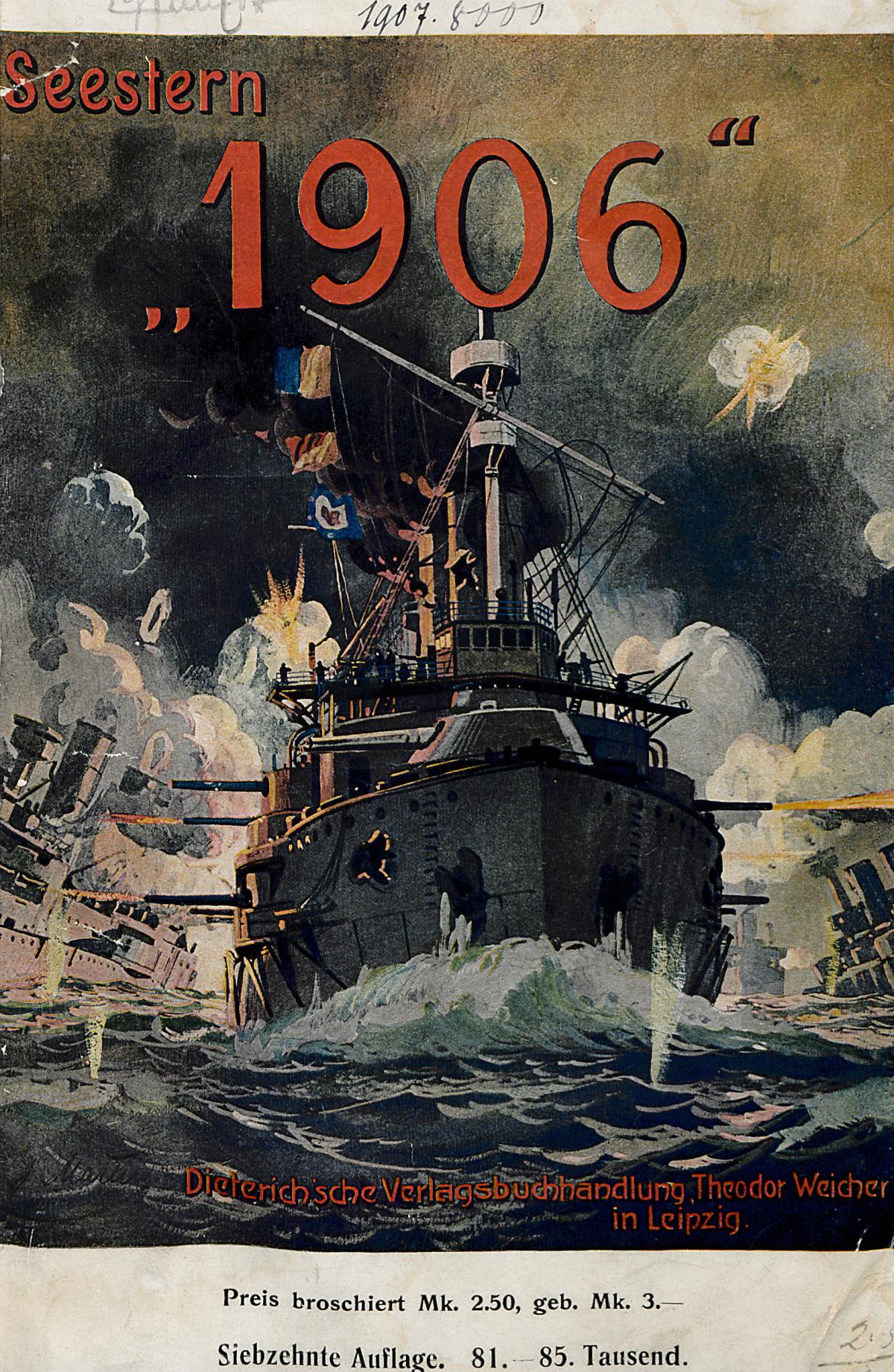

The cover of Seestern’s Der Zusammenbruch der alten Welt (1906)

In 1906, newspaper editor and naval writer F. H. Grautoff, writing under the pseudonym, Seestern, penned the novel Der Zusammenbruch der alten Welt (translated to English as The Collapse of the Old Word, and later re-titled Armageddon 190-). In his story he wrote:

They [Britain and Germany] had not stayed to consider that a war in Europe, with its manifold intricate relations with the new countries over the seas, the millions of whose populations obeyed a handful of white men, but grudgingly, must necessarily set the whole world ablaze.

His account of an imaginary war foresaw the exhaustion of European nations, and the shifting of power to the United States and Russia.

Today, we have our own contemporary examples. Fictional accounts of a future world in which global warming is either running amok or has already thrown the world into an apocalyptic hellhole abound. Arctic Rising by Tobias Buckell is worth checking out, as are all of Paolo Bacigalupi’s novels. Popular movies include Silent Running, Blade Runner, Water World, Snowpiercer, Spielberg’s AI, WALL-E, Interstellar, and Mad Max: Fury Road. Taken together, these fictional accounts serve as cautionary tales that work to entertain, horrify — and hopefully motivate a response.

Industrial Horrors

Climate scientists have been tracking the steady ascent of global temperatures for decades now. Back in 2004, a Naomi Oreskes survey found that 97 per cent of climate science papers are in agreement that the warming trend is anthropogenic. It’s now obvious to the point of near-certainty that human activity is responsible for the current climate crisis.

In 1914, Europe was also having to contend with the consequences of its newfound scientific, technological, and industrial capabilities. Things had changed dramatically since the times of Napoleon, and astute military leaders knew it. But like our leaders of industry today, many of them wilfully ignored or dismissed it. There was too much to lose by perturbing the status quo — or so they thought.

“The reluctance of Europe’s military to come to terms with the new ways of war can be explained partly by bureaucratic inertia; changing such things as tactics, drills, or training methods is time-consuming and unsettling.” Margaret MacMillan

Aside from the new industrial might of the great European nations, the most significant development was the introduction of modern weaponry. Hew Strachan explains:

In 1815, at Waterloo, the infantry soldier’s musket had a maximum effective range of 137m and a rate of fire of two rounds a minute; a century later, the infantry rifle could range almost a mile, and — fed by a magazine — could discharge ten or more rounds a minute. A machine-gun, firing on a fixed trajectory, could sweep an area with 400 rounds a minute…And in 1897 the French developed the first really effective quick-firing field gun, the 75mm…[which] could fire up to twenty rounds per minute without being relaid on the ground…Advances in artillery made permanent fortifications vulnerable, and their modernization with reinforced concrete costly…The strength of the defensive and the probability that attacks would soon get bogged down in a form of siege warfare led soldiers to warn against any exaggerated expectation of quick, decisive victory.

Owing to population growth, conscription, and soldier re-training protocols, all continental powers had massive standing armies by the end of the 19th century, while Britain’s relatively tiny army was offset by its first-class navy. Backing these formidable forces were the respective industrial sectors of each nation.

Machine Gunners from the detachment under General Mishchenko in the Russo-Japanese War, 1904-05 (Credit: All World Wars)

Despite the overwhelming evidence, military planners still insisted that a massive offensive force, with a hefty dose of individual elan and fortitude, could defy the changing battlescape. As The Times’ military correspondent Charles a Court Repington wrote in the autumn of 1911 after attending German field exercises, “No other modern army displays such profound contempt for the effect of modern fire.” He was wrong, of course — virtually every army in Europe shared the same irrational contempt.

And it’s not as if military thinkers didn’t have real-world examples to remind them that things had changed. The shockingly lengthy American Civil War, with its extensive casualty lists, was the first sign that the Napoleonic era of warfare was coming to a close. The Turko-Russian War of 1877 provided another example. But the real exemplar of the military shift arrived with the Russo-Japanese war of 1904-05 — a conflict that featured dramatic naval battles, lines of trenches, barbed wire, foxholes, heavy artillery, and of course, machine guns.

Most military thinkers casually dismissed the great losses of manpower in those wars as a deficiency in tactics. They also believed that Europeans wouldn’t turn machine guns against fellow Europeans en masse, and that the weapon should/would only be used to subdue native populations, as the British had been doing in South Africa. The solution, they thought, was just a matter of finding the right approach. Tragically, this “right approach” almost always involved more offence.

This was the era, after all, when military tacticians fetishised the offensive. After its humiliating defeat in 1871, the French vowed to take it to the enemy next time, leading to the so-called “cult of the offensive”. The militaries of other nations adopted a similar attitude. As MacMillan writes: “The reluctance of Europe’s military to come to terms with the new ways of war can be explained partly by bureaucratic inertia; changing such things as tactics, drills, or training methods is time-consuming and unsettling.”

A French soldier shot at Verdun. The combination of heavy artillery, high-powered, quick-loading rifles, and machine guns contributed to the primacy of defence in WWI. (Credit: Independent)

Adjusting to the realities of anthropogenic climate change is likewise proving to be “time-consuming” and “unsettling”, while “bureaucratic inertia” now works alongside economic frugality. Industries have been slow to overhaul their modes of production, while governments, with their lack of teeth, courage, and imagination, have failed to compel or properly incentivise them. Change hurts, absolutely, but as the horrors of August 1914 demonstrated — a month in which millions of soldiers lost their lives owing to these outdated tactics — failure to act can produce even worse outcomes.

The Cost of Inaction

The inability to avert war, and the stubborn persistence to keep it going even when it became obvious that it was a political, social, and humanitarian nightmare, left lasting scars on the continent and the world as a whole. McMillan writes:

Europe paid a terrible price in many ways for its Great War: in the veterans who never recovered psychologically or physically, the widows and orphans, the young women who would never find a husband because so many men had died. In the first years of the peace, fresh afflictions fell on European society: the influence epidemic (perhaps the result of churning up the rich microbe-laden soil in the north of France and Belgium which carried off some 20 million people around the world; starvation because there were no longer the men to farm or the transportation networks to get food to the markets; or political turmoil as extremists on the right and the left used force to gain their ends. In Vienna, once one of the richest cities in Europe, Red Cross workers saw typhoid, cholera, rockets, and scurvy, all scourges they thought had disappeared from Europe. And, as it turned out, the 1920s and 1930s were only a pause in what some now call Europe’s latest Thirty Years War. In 1939, the Great War got a new name as a second world war broke out.

By the time WWI was over, some 11 million soldiers lost their lives, in addition to 7 million civilian deaths.

Our inability to stave off the effects of climate change could produce equally calamitous results. Rising sea levels will threaten coastal areas, droughts will turn fertile areas into deserts, natural aquifers will run dry, storms will lash vulnerable areas with unprecedented ferocity, and diseases, once relegated to equatorial regions, will move into increasingly northern and southern latitudes. Refugees will pour out of stricken areas into nations that will struggle to accept and accommodate them. Entirely new social and geopolitical tensions will arise, leading to social unrest, new animosities, and extremist politics.

Welcome to modern war: The Somme, 1916 (Credit: John Warwick Brooke/Imperial War Museums)

The cost of inaction will be grossly outweighed by the consequences.

World War I was not inevitable. Historians point to the precarious system of alliances, the unnecessary Naval arms race between Britain and Germany, the influence of opportunistic heads of state, the string of errors and deceptions committed by diplomats during the July Crisis (including the refusal of Austria-Hungary and Germany to attend a conference proposed by Britain), and a slew of many other factors. Had more cooler and rational heads prevailed — and had the warnings been heeded — the crisis could have been averted.

As the Paris Climate Change Conference continues this week, it’s a lesson worth remembering.

Sources: Hew Strachan: The First World War [G. J. Meyer: A World Undone [Margaret MacMillan: The War That Ended Peace [Alexander Watson: Ring of Steel |]