Fleeing violence and starvation in their native country, the refugees arrived in their new home only to be ridiculed in the press, subject to overt racism, and faced with persecution in their places of worship. Sound like recent headlines? This was the reality for the first Irish refugees to come to the US. It hasn’t gotten much better in the last 150 years, either in the US or around the world.

AU Editor’s Note: this feature specifically refers to the United States’ attitudes to refugees, but I thought it was interesting and thought-provoking enough to share. — Cam

America likes to call itself a melting pot but this has yet to be proven true when it comes to refugees. The Irish who escaped famine and political unrest at home by coming to the US in the late 1800s were only the first group to be confronted with a radically unfriendly culture. An entire political party, the Know Nothings, was founded with the express purpose of preventing Irish Catholic refugees from entering the country. They didn’t succeed, but their legacy is felt to this day through fear-mongering, exclusionist policies.

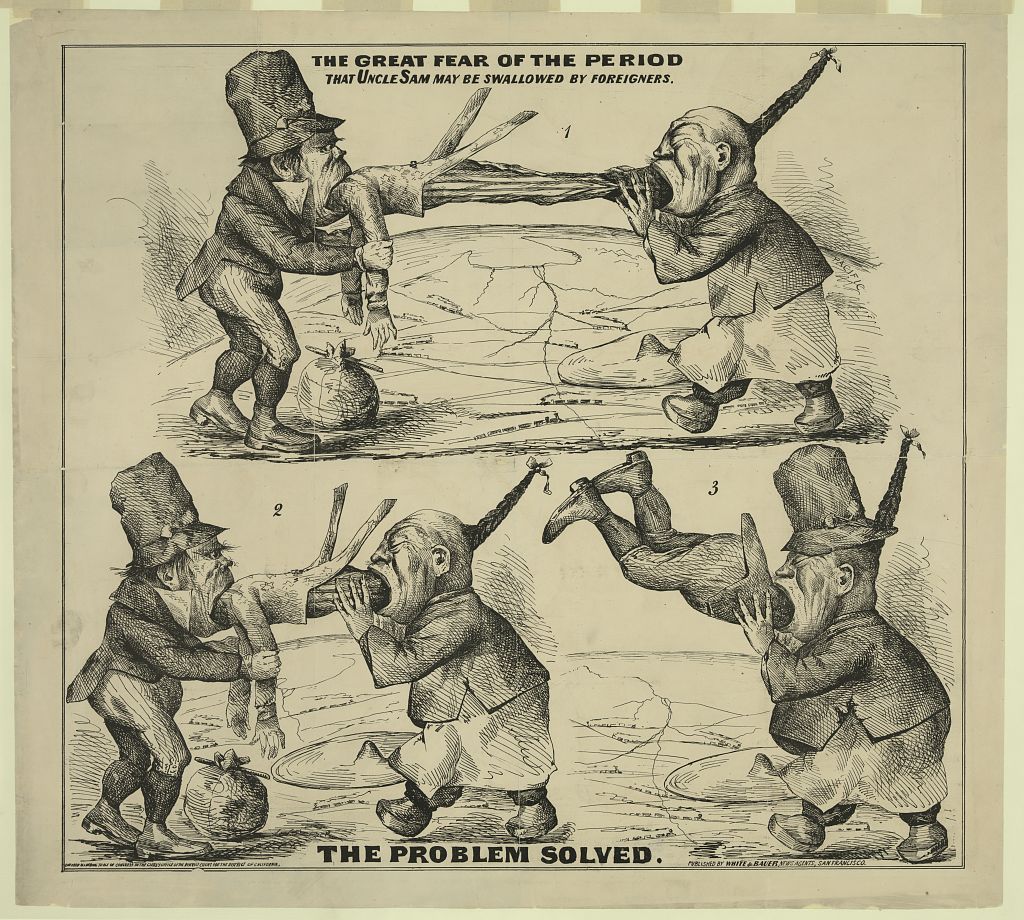

The great fear of the period That Uncle Sam may be swallowed by foreigners, lithograph by White & Bauer circa 1860, Library of Congress.

The ethnic group might change — swap Irish for German, Italian, Mexican, Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, Bosnian, Cuban, Iraqi, and now Syrian — but the sentiment remains the same. In a country where the vast majority of the population is descended from immigrants, many Americans cling to dangerously nativist beliefs.

Historically, refugees have been irrationally feared due to their ties to religious zealotry, disease, or crime. But now, the argument against refugees has become an issue of national security. Some are claiming that refugees leave the door open for terrorism, a claim that’s been amplified after this month’s Paris attacks.

With the president himself planning to increase the number of refugees in the US resettlement program, possibly expanding the program to welcome 100,000 people per year by 2017, a whole new wave of anti-refugee fever has swept the country. But why?

We Don’t Think Refugees Have Anything In Common With Us

The horrific episodes of genocide in places like Bosnia and Darfur represent the worst possible escalation of ethnically motivated fears, where one group attempts to obliterate another. But neuroscientist David Eagleman has been determined to figure out where the brain plays a role — how do humans decide it’s ok to kill their neighbours? It turns out that we have a harder time empathizing with those who we believe are fundamentally different than us.

The place in the brain that registers pain is called the “pain matrix.” What’s interesting from a neurological standpoint is that this is also the same place where we register the pain we perceive being felt by others. So watching someone be in pain, and actually being in pain use the same neural pathways. This is empathy — actually “feeling their pain.”

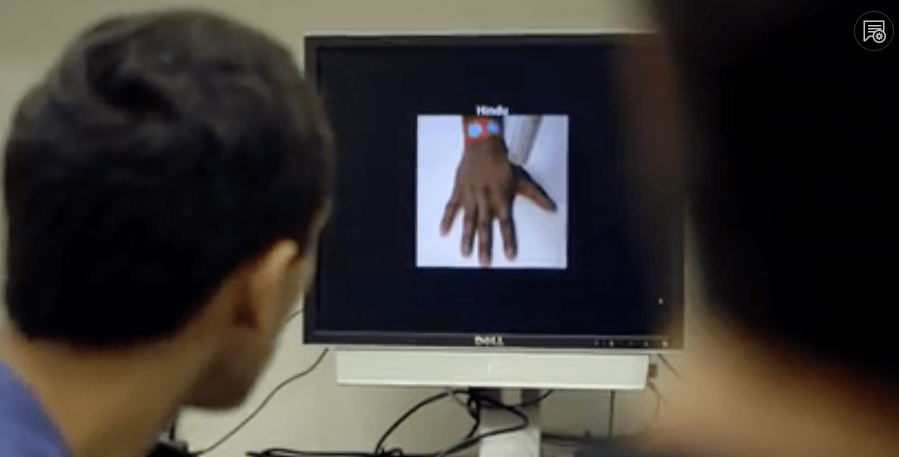

An image from the empathy study by David Eagleman his “Why Do I Need You?” episode of The Brain.

Eagleman scanned 130 people’s brains in an MRI machine as they watched video of six hands with six different labels — Christian, Atheist, Hindu, Jewish, Muslim, Scientologist — one of which was randomly stabbed by a syringe. When people saw a hand of group they believed they belonged to (an in-group) their pain matrix was activated. For groups they didn’t feel like they belonged to (an out-group) there was little or no response. It didn’t even come down to religious beliefs — even atheists cared more about other atheists.

This explanation of empathy is key to what Kristin Haltibner calls the “immigration threat narrative,” in a study she co-authored in the Journal of Intercultural Studies that looked at the treatment of refugees in the US, UK, and Australia. Although “interest-based threats” like national security are important to people trying to keep refugees out, it’s “identity-based threats” which end up being more difficult to overcome — the sense that people are “different” from the group we identify with. “It seems as if Islam has become radicalised and the fear is of the implementation of some sort of Islamic culture,” she says. “This is also interesting given that Syrians are white — they have legally been considered white since a Supreme Court ruling in 1909.”

The New York Times VR app profiled three refugee children in “The Displaced“.

There has been a lot of talk about how virtual reality, with its almost disorientingly immersive experiences, can engender empathy. After a series of stories which helped bring the refugee crisis in Europe to international attention, the three refugee children (if you have not watched it yet, I highly recommend it; you don’t need a VR viewer).

Whether or not you believe in a neuroscience connection between Google Cardboard and the brain, there is no doubt that these highly affective stories use an innovative medium to present refugees as relatable human beings with the same shared experiences — not necessarily part of any particular group. And that might help to change people’s minds.

We Don’t Think Refugees Are Good For the Economy

In September, when the most brutal details about the Syrian refugee crisis began to sweep through the internet, this tweet went viral. In fact, it continues to be shared with some frequency to this day.

A Syrian migrants’ child. pic.twitter.com/sjBxuInpEp

— David Galbraith (@daveg) September 2, 2015

It was a powerful attempt to put a face to the crisis (even if not quite accurate — Steve Jobs’ birth father Abdul Fattah Jandali did leave Syria to attend college in Beirut, then moved from there to New York City, but did not officially come here as a refugee). You’ve probably seen similar memes touting the cultural value of other refugees.

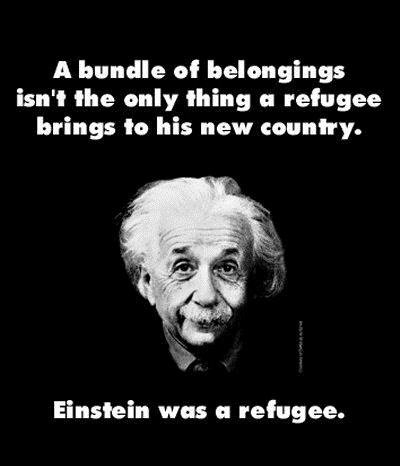

Albert Einstein fled Germany, Sergey Brin fled the USSR, and their stories have been turned into memes.

The argument that one refugee (or the biological son of one refugee) can launch a company like Google or Apple makes the cause immediately relatable to millions, but these memes also make a statement about the economic impact of refugees, something that’s been almost universally proved to be positive. Civic leaders from Cleveland to Seattle have spoken out about the value of refugee populations in their cities. And Syrian migrants specifically are higher educated than many native-born populations, according to this thorough study by the Migration Policy Institute.

Even the countries which are supporting refugees temporarily in camps are seeing benefits. In Lebanon, for example, which has welcomed over a million Syrian refugees since 2011, the economy is growing much faster than before, according to a Brookings study. What’s more, the influx of refugees has likely helped Lebanon weather the impact of civil war in a neighbouring nation.

We Don’t Actually Believe Refugees Will Assimilate

Remember all those fondue-like metaphors for US culture? We say that we’re a country built on religious freedom and acceptance of all beliefs, but many Americans are outright afraid of anything that will change that culture too much.

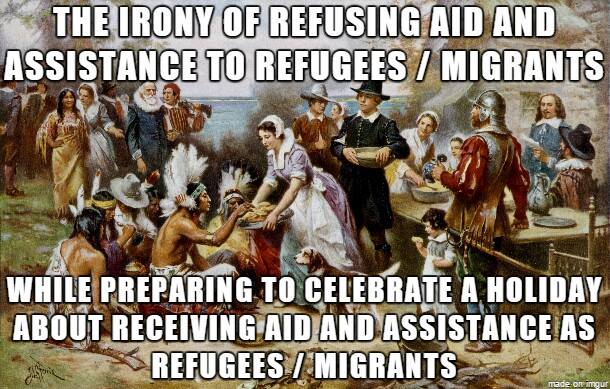

This particular image has been shared almost 90,000 times on Facebook.

Some Americans even believe that refugees will bring along the ideology they’re fleeing. As Jamelle Bouie writes at Salon, it’s an echoing refrain throughout American history:

You saw it in the late 1930s, when Americans faced Jewish refugees from Nazi Germany, and had to choose: Would we take the victims of Hitler’s anti-Semitism, or reject them? On the question of refugee children, at least, Americans said no: 67 per cent opposed taking in 10,000 refugee children from Germany, according to a 1939 poll from Gallup.

This was not just a hypothetical question. It was a real-life situation where 900 Jewish refugees from Nazi Germany, most of whom were children, were denied entry to the US when their ship was turned away from Florida shores. The ship returned to Europe where about a third of the refugees ended up being killed in the Holocaust.

The assimilation argument seems to apply most to the national security debate, so here are some numbers. The US has resettled three million refugees since 1975, and three of those resettled refugees have been arrested for terrorist activities. If ISIS really wanted a few terrorists to infiltrate the country through the US’s refugee resettlement process, it would be the most inefficient use of their time and resources. After lottery-winning odds just by being selected by the United Nations — less than one per cent of refugees are recommended for resettlement — refugees are screened by four federal agencies in a vetting process including biometric scans and health screenings that can take several years.

John Oliver explains the rigorous steps and, oh wait, the House just added a few more.

Oh, and about all those governors pledging to keep refugees out — it’s not really up to the states to decide. Once a refugee is resettled, she’s allowed to move freely between state borders — just like any native-born American can.

Although the overall benefits are positive, resettlement doesn’t have any immediate impact on any particular city. They get jobs. They learn English. Any fear that resettlement will somehow “change” culture is nativism at its worst.

And Yet, No One Helps Refugees Better Than The US

About four million Syrians have left their country since the beginning of its civil war in 2010. About 600,000 of those refugees have arrived in Europe so far this year, a number which may reach one million by the end of 2015. At least 3200 fleeing refugees have died this year alone.

Compare those numbers to this figure: Since 2010, the US has settled 2261 Syrian refugees in 36 states. Even with new policies in place, it’s only possible that about 10,000 Syrian refugees per year could be allowed to resettle in the US. That’s not a lot. We could be doing more.

There’s a lot of trouble with the international system, but here in the US it works very well, says Bill Davis, Director of the Martin Institute of International Studies at the University of Idaho. Besides helping Syrian refugees to put some serious geographic distance between them and their conflict, the US provides better living conditions and more economic stability for refugees.

But this isn’t happening because of some mandate at the federal level, this is largely thanks to the vast network of small NGOs and local nonprofits which devote time and money and personal attention to the resettlement process. “The US doesn’t have a strategic overarching need to do this — we do it because it’s the right thing to do,” says Davis. “And when it happens, it’s the most hopeful thing ever.”

This is the chance for the US to step up to the geopolitical stage and serve as a model for how refugees are treated all over the world. President Obama can allow more refugees to come into the country, but the real change will happen city by city, block by block, neighbour by neighbour.

Here’s how to donate directly to the UN Refugee Agency or find a group to support near you.

Protesters on both sides of the Syrian refugee resettlement issue in Olympia, Washington. AP Photo/Rachel La Corte.