Like many soul-searching 1990s adolescents, I was obsessed with Nike Air technology. I’d pore over the latest innovations, from visible forefoot air to tuned air to other types of air. I’d even buy used joggers at the trash and treasure market and tear them apart to inspect the air. As my young brain developed and my understanding of biomechanics advanced, however, I came to a realisation: Nike Air is bullshit.

I’m not trying to say that Nike Air is useless. The gas-filled sacks of cushioning revolutionised the jogger world when it was introduced over 30 years ago. As a fashion statement alone, the introduction of Air Max helped to create a cottage industry of joggerheads and collectors with closets full of unworn shoes. However, there’s very little real science — despite Nike commercials that say otherwise — supporting the idea that filling running shoes with pressurised air makes you a better athlete. Recent research actually suggests the opposite.

But even Nike itself now considers itself a marketing company. And its greatest act? Convincing anyone that Nike Air technology was more than a demonstration of Beaverton’s historically profitable and often deceptive brand-building prowess.

The Early Days in Oregon

It wasn’t always like this. Back in 1964, former University of Oregon runner Phil Knight and his former coach Bill Bowerman founded the company in order to help the running community get access to the best shoes. They called it Blue Ribbon Sports (BRS), the nascent company started out as a distributor for Onitsuka Tiger. Apparently Bowerman sold most of the shoes out of his trunk at track meets.

It didn’t take long for Knight — who was finishing up his MBA at Stanford — and Bowerman to realise they wanted to do their own thing. Bowerman had designed a cushioned running shoe that Onitsuka released in 1969 as the Tiger Cortez. Around the same time, though, he and Knight started working with a factory in Japan to produce their own line of joggers. They called it Nike. And do you know what one of the first models was? The Nike Cortez.

Onitsuka didn’t even realise Bowerman had repurposed the design until an official visited the old BRS warehouse in Los Angeles. Nevertheless, a court decided that both companies could make the shoe. In effect, Knight and Bowerman were selling the same shoes to the same runners, except they’d replaced the Onitsuka logo with their own. A local student named Carolyn Davidson designed the “Swoosh,” and Nike paid her just $US35. Over a decade later, Knight gave Davidson “a gold Swoosh ring embedded with a diamond… and an envelope containing Nike stock” for her work.

And so, Nike’s tradition of clever marketing and borderline trickery had begun. Knight and Bowerman realised early on that they weren’t necessarily selling a unique product. They were selling an idea, too. The Swoosh, the athlete endorsements, the slogans — it all added up to a brand that encouraged people to believe in products rather than performance.

NASA and the Birth of Nike Air

Maybe it’s not surprising that in those early days, Nike crossed paths with NASA; at that time, just about every new invention seemed to trace itself back to the Apollo missions somehow. Nike Air was no exception.

Nike was ready for a boost by the end of the ’70s. The company enjoyed explosive success after its endorsement of record-smashing distance runner Steve Prefontaine and the release of the famous Waffle Trainer — for which Bowerman developed the sole by pouring rubber into his wife’s waffle maker. Then, in 1978, Nike revealed the next big thing: the Air Tailwind.

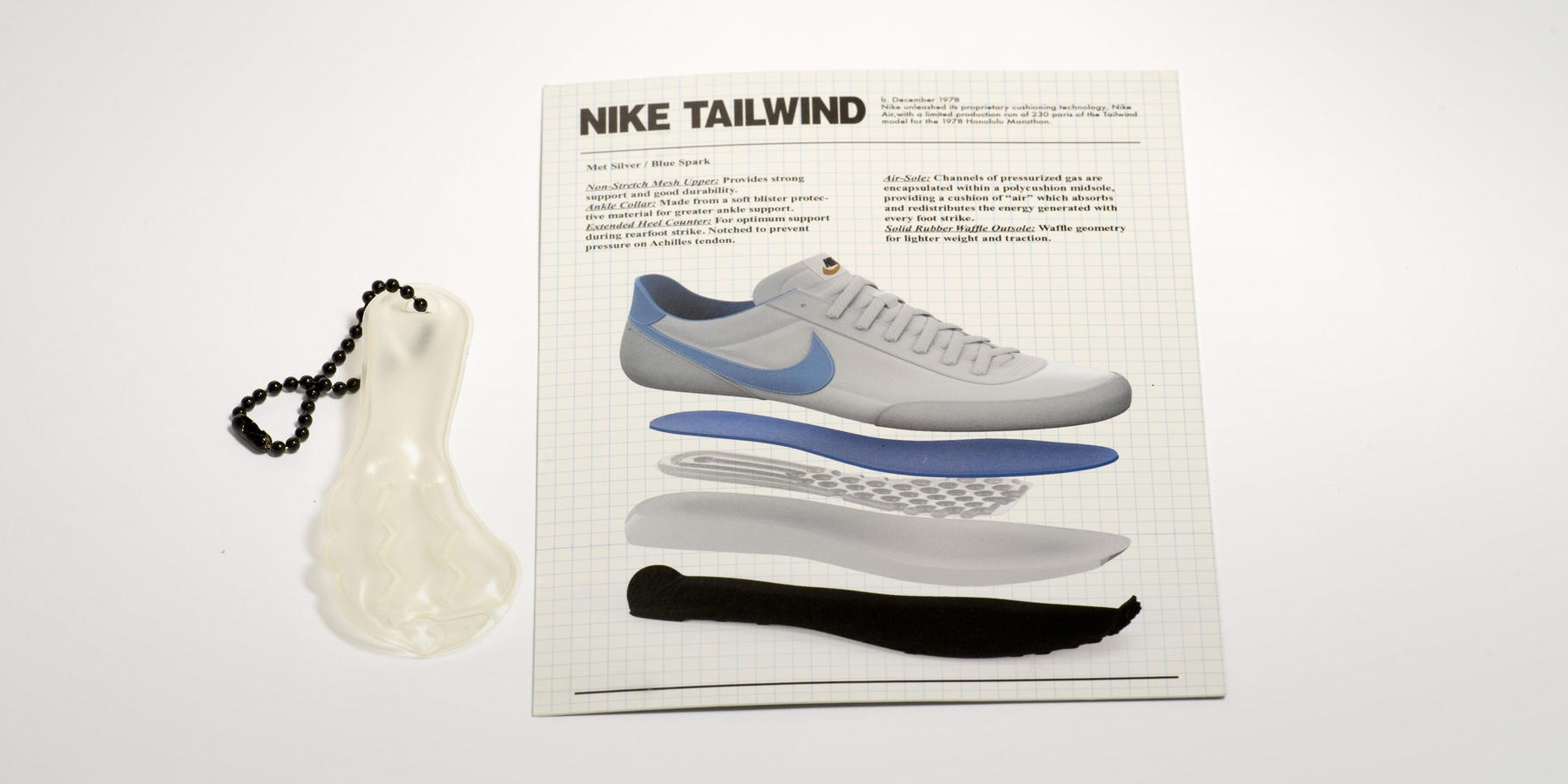

First produced for the Honolulu Marathon, the Nike Air Tailwind included new technology developed by former NASA engineer M. Frank Rudy. Rudy’s innovation repurposed an aeronautics technique called blow rubber moulding. It was once used to create astronaut helmets for the Apollo missions and later enabled Rudy to design a hollowed-out midsole in which he embedded polyurethane pouches filled with dense gases.

Rudy patented the design in 1979. The idea — as well as the branding strategy — hinged upon the assumption that running on air would provide superior cushioning, since the sacks of gas wouldn’t wear out after repeated use. Nike Air was initially marketed to elite runners, though that strategy shifted over time to include anyone with $US100 or more to spend on joggers.

In the beginning, consumers had to trust Nike on this air-cushioning claim, as the Nike Air technology was invisible in the original Tailwind shoes. One could ostensibly tear the shoe apart to find it hiding above the patented Waffle outsole, but it would be a few more years before Nike would put its new trick on display.

Nike Air Max and Profitable Transparency

By the greedy ’80s, the Air Force 1 and original Air Jordan joggers had taken over the world of basketball. Nike had also cultivated its image as an edgy brand — so much so that after the NBA banned the original Air Jordans for not meeting its colouring guidelines, Nike actually paid Michael Jordan’s fines as long as he kept wearing them on the court. But the company continued to innovate and take Nike Air technology to new levels.

Nike became a billion dollar company in 1986, around the same time that it was putting the finishing touches on a massive upgrade to its line of air-cushioned shoes. The following year, the company released the Air Max 1 running shoe, featuring a much larger air pouch and a little window into the cushion on the side of the heel.

This involved a little bit of reengineering. What had been a thin, foot-shaped container for the air cushion would be redesigned to resemble a squished Klingon starship, the edges of which held the visible air. In the middle, there was a beefy pouch with supports for primary cushioning. This concept would become a defining brand for Nike, especially in terms of establishing the company’s superiority in technology-driven design. The air wasn’t just visible either; you could poke the packet of gas and feel the bounce.

Air Max shoes put the technology on display without offering too many clues about how it worked. (It’s honestly just a polyurethane pouch filled with inert gas.) That simplicity remained key to the overall design. The original Nike Air Max I, designed by the now-legendary Air Max maestro Tinker Haven Hatfield, established a formula that would help Nike bring in billions of dollars in the decade after it was introduced.

“The shoe was designed to breathe, be flexible and fit well but the fact it had the air window in the sole and the frame colour around it meant it looked a lot different than other shoes in its day,” Hatfield told The Guardian a couple years ago, speaking about the Air Max line. “It was easy to recolor it and do it over and over again, it wasn’t overdesigned.”

The evolution of the Air Max lineup hinged on a pretty straightforward set of design principles for the next decade. The jogger was not only marketed as extra air-filled but also rather unique yet personalised, since each model came in multiple different colorways with new releases. Nike changed the shape and composition of the Air Max technology over the years, selling the public on the feigned innovation that came with each subsequent generation of Air Max joggers.

That said, the principle of air cushioning being a one-size-fits-all solution to comfort and performance is pervasive in the company’s marketing strategy. The “strangely scientific” tagline in this 1994 commercial for Air Max 2 is a great example:

Suddenly, joggers felt a little bit less like slabs of foam and rubber that you strapped to your feet and more like a gadget that made you a better athlete. Hatfield even said that the design of Air Max was inspired by the Pompidou Center in Paris, a nod to its legendary architects Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers. Indeed, the technology made joggers look futuristic. As to whether or not Air Max shoes delivered on that performance promise is a subject of great debate.

A Quick Family History of Air Max and Its Offspring

For the purposes of this history, I’ll focus on the running shoes since the Nike Air technology was originally built for competitive track athletes. It’s also important to emphasise how Nike marketed the extra cushioning as a good thing for all runners. This claim has proved to be rather dubious in recent years. Experts say shoe companies like Nike are to blame.

“Part of the problem is the shoe industry as a whole does a really horrible job of matching footwear to feet,” physical therapist and biomechanics expert Jay Dicharry, told The Atlantic last year. “All the methods used to fit feet to shoes don’t really hold up as valid ways to classify runners and to match shoes.”

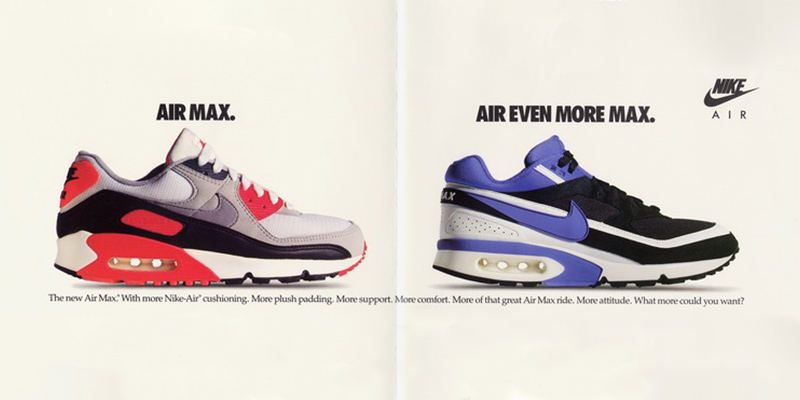

Along those lines, the main thrust of Air Max innovation boiled down to the grand American ideal that more means better. This philosophy is wonderfully expressed in the now iconic Air Max ads from the 1990s. Even the aesthetic of simple black text on stark white backgrounds emphasises that simple but bold formula. You can see this Madison Avenue tradition as far back as the Mad Men-era Volkswagen ads and continues to this day with pretty much every Apple ad in the past ten years.

“[If you like] Air Max,” the ads seemed to say, “[You’re going to love] Even More Air Max.”

The “Even More” concept evolved from there in absurd new ways. While the original Air Max from 1987 brought more visible air volume into the mix, subsequent brought brought both more visibility and more volume. The Air Max 90 (pictured above to the left) included a slightly larger air pack and a very slightly bigger window. Ditto for the Air Max IV, also known as the Air Max BW (pictured above to the right). The colloquial “BW” refers to “Big Window,” since the window into the air is… extra big.

It gets crazier from here on out. In 1991, the same year of the Air Max BW, Nike came out with the Air Max 180 featuring an “Air-Sole to outsole with no interruptions.” In other words, you could see the sack of air cushioning from the bottom of the shoe as well as the side.

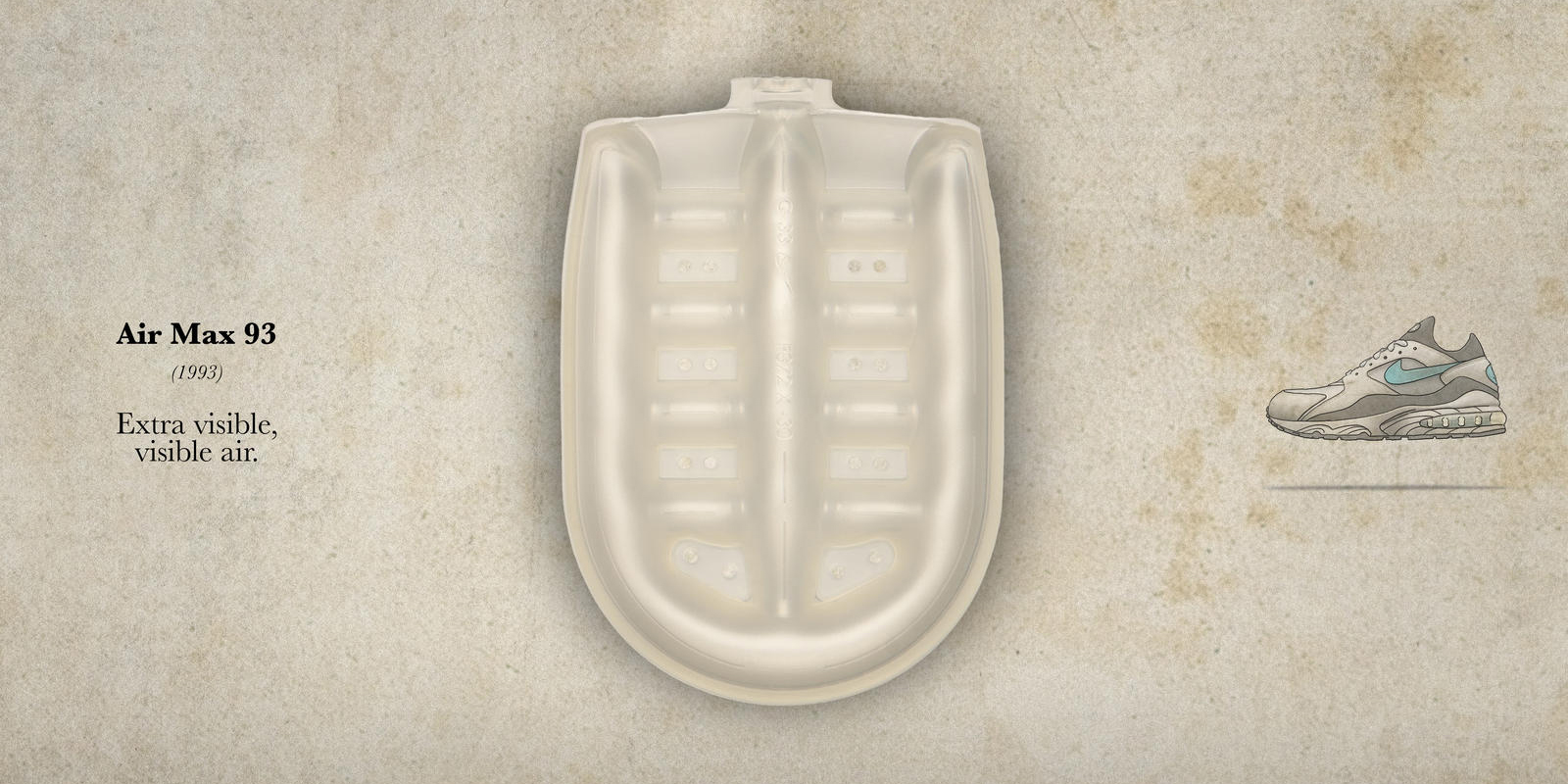

Then came the Air Max 93 with visible air that wrapped around the whole heel of the shoe. This pouch looks like a more symmetrical Millennium Falcon.

It does look very cool, and I would have died to own a pair like the rich kids in my fifth grade class. But did the Air Max technology really make them run faster and jump higher? Nike didn’t exactly say.

Instead, they made a kitschy commercial starring Quincy Watts, an American runner who’d just won two gold medals at the 1992 Olympics in Barcelona. He was not wearing the Air Max 93 joggers when he won, of course. But he looks very bouncy in the commercial which features an off-colour joke about a “super-cushioned wife.” (She’s an overweight opera singer.)

So continues the steady march of marketing: Nike uses star athletes to promote new technology without clearly explaining how the benefits. The message always seems to emphasise how more air equals better shoes. Visible air looks cool, for sure. Super-cushioning isn’t always a good thing, though.

Nike made a breakthrough with the Air Max 95, not only in terms of technology but also design. Footwear designer Sergio Lozano took a dramatic turn away from the simplicity of the earlier Hatfield-designed joggers, and things got weird. The Air Max 95 featured a thin wafer of visible air in the front of the show as well as a bulbous new pocket in the heel. With the original grey and neon green colorway, the whole getup resembled a prop from the popular scifi thriller Alien.

In addition to edgy design, the extra Air Max technology made the shoes a real fashion statement. But you didn’t really see world class athletes winning events with these things during the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta. Nike-sponsored athlete Michael Johnson wore custom-made gold spikes that had virtually no cushioning. Obviously, a sprinter wouldn’t wear squishy trainers on race day, but the idea brings us back to the fact that there is no singular technology that makes shoes better for everyone.

Max Air Max

By the end of the 90s, trends in the running shoe industry were heading more towards the sensible than the sensational. New Balance and Asics emphasised things like quality construction and increasingly personalised options for stability and cushioning. Nike, on the other hand, went off the rails with the Air Max technology.

After the Air Max 95 proved that pressurised sacks of gas weren’t just for the heel of the shoe, Nike basically inched its way towards a completely air-filled midsole. The Air Max 97 came with one giant air pouch that stretched from the heel to the ball of the foot.

Then Nike introduced something called Tuned Air — apparently different types of pressure in different parts of the shoe did something — in the Air Max Plus. Tuned Air involved adding mechanical elements to the shoe that would provide the right amount of support in the right areas. (Nike was actually heading in the right direction with this custom cushioning idea.) There was also a whole line of shoes featuring Zoom Air technology which Nike says “turns the pressure of each step into ultra responsive energy for the next.” By the time 2006 rolled around, Nike did the inevitable and release the Air Max 360, a shoes with visible air that stretched from heel-to-toe.

So we’ve gone from “Air Max” to “Even more Air Max” to “Literally the maximum amount of Air Max that will fit in a shoe.” Here’s the entire evolution, from 1987 to 2015:

If Nike’s marketing team were telling the truth, these joggers should have been bouncing runners towards personal bests left and right. If Nike’s commitment to leveraging technology to empower champion athletes were legitimate, we should have seen Olympians standing waving to the crowd while floating on a layer of Air Max gadgetry. But that never happened.

In fact, quite the opposite proved to be true.

Nike Calls Bullshit On Its Own Bullshit

Years ahead of the release of the Air Max 360, a pair of Nike sales reps visited sponsored athletes at Stanford University to see which of its latest running shoes they liked best. Stanford head coach Vin Lananna welcomed them with sobering news: His athletes performed best when they trained barefoot.

This anecdote appears in Born to Run, a book by barefoot running enthusiast Christopher McDougall. The author talked to legendary runners from cultures around the world, including the Tarahumara of Mexico who run hundred-mile races wearing nothing but loose rags and thin leather sandals. Speaking to experts on the human body, McDougall found that the last 20th-century fad in super-cushioned shoes actually correlated with an increase in injuries.

“A lot of foot and knee injuries currently plaguing us are caused by people running with shoes that actually make our feet weak, cause us to over-pronate (ankle rotation) and give us knee problems,” Dr. Daniel Lieberman, a professor of human evolutionary biology at Harvard, told the author. “Until 1972, when the modern athletic shoe was invented, people ran in very thin-soled shoes, had strong feet and had a much lower incidence of knee injuries.”

Amidst a flurry of reports like this, barefoot running — as well as shoes that simulate the experience — took the world by storm. After the top athletes in America told Nike they were maxed out on gimmicky features, Nike decided to launch an entire new line of running shoes that emphasised everything that Air Max was not.

So Nike did its research and came out with the next big thing: Nike Free. It’s a shoe designed for minimal cushioning and maximum flexibility. (It’s like taking the Air Max 360 and sucking out all the air.) What’s more is that the design comes in gradients, with a numbered naming system to indicate how much cushioning the shoes provide. The Nike Free 3.0 is most like running barefoot, and the now discontinued Nike Free 7.0 offered more cushioning. That’s the original Nike Free 5.0 V6 above.

“We found pockets of people all over the globe who are still running barefoot, and what you find is that, during propulsion and landing, they have far more range of motion in the foot and engage more of the toe,” Jeff Pisciotta, a senior researcher at the Nike Sports Research Lab, told McDougall. “Their feet flex, spread, splay and grip the surface, meaning you have less pronation and more distribution of pressure.”

The first Nike Free joggers came out in 2005, and the technology now one of the cornerstones of Nike’s running shoe line up. As Nike designers admit in a promotional video, the sole is “just a solid piece of foam.”

What’s Next?

Since the birth of the barefoot running craze ten years ago, plenty of research has emerged about how too little cushioning can also be bad, too. Over the past few years, more runners are moving back to cushioned shoes.

So at this point, you should be wondering whether the cushion pendulum will just continue swinging back and forth forever. That revolutionary idea of putting inert gas into polyurethane modules that softened the blow of each step still makes sense for some runners. Free makes sense for others. In the end, it really depends on your foot and your gait. You need the right shoe for you, despite what’s en vogue.

And then there’s the vast sea of Nike fans for whom jogger technology isn’t just about running. It’s about fashion. People buy shoes for a lot of different reasons, and Nike is reissuing old joggers from the Air Max lineup left and right. The company is also reincorporating classic Air Max technology into new designs and even splicing Air Max technology into Nike Free soles.

In the end, Nike’s mercurial take on technology is a lot like the fashion industry’s relationship to certain recurring trends, like fur or metal. They come and go, without much rhyme or reason. There’s very little science involved in Nike’s constantly-evolving ideas about shoes. Yet for fans, the bullshit seems to be half the fun.

[Nike, The Atlantic, The Guardian, Harvard Business Review, New York Times]

Images via Nike