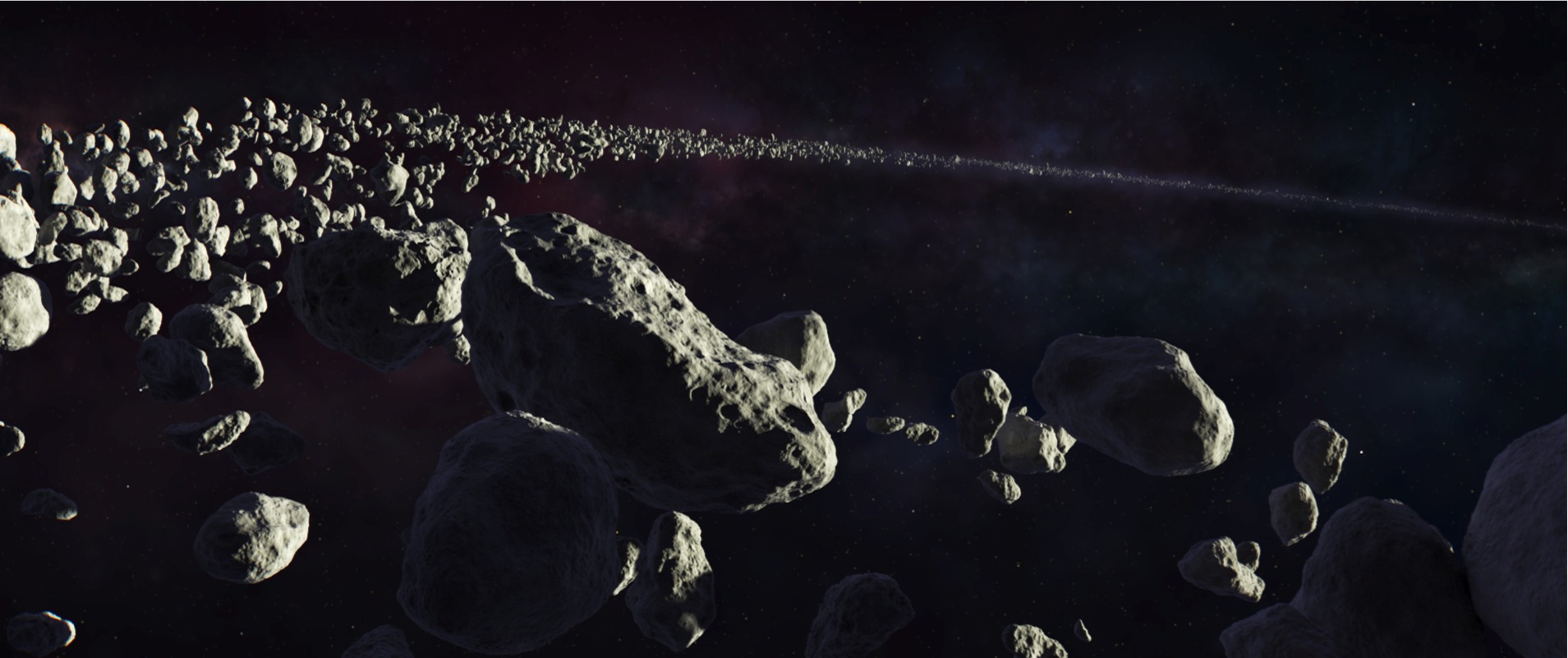

The cosmic shock came out of nowhere. One day, circa 66 million years ago, a chunk of space rock about 9.6km in diameter struck the Earth in what is now the Yucatan Peninsula, sparking the fifth mass extinction in Earth’s history. But what if the massive bolide had missed? What would life be like now if that mass extinction had been canceled? Pixar’s The Good Dinosaur imagines just that.

I haven’t seen the film just yet. Like everyone else, I’ll have to wait a few more weeks to watch the adventures of Arlo and his feral human sidekick Spot. But ever since the movie was first announced in 2012 I’ve been anxious to see what Pixar was going to do with its alternate evolutionary history that brings non-avian dinosaurs and humans together. A lot can happen in 66 million years, and I’ve been hoping that the film’s creators would go crazy with designs for new, strange dinosaurs never seen before.

A cult favourite among paleonerds set my expectations high. In 1988 geologist and author Dougal Dixon published The New Dinosaurs: An Alternative Evolution with the exact same premise as the new Pixar movie. Dixon ran riot with his speculative creatures, imagining that dinosaurs and other Mesozoic creatures would evolve to fill many of the ecological roles played by mammals today. Instead of anteaters, there would be the dinosaurian “Pangaloon”, and instead of the aye-aye, the “Nauger” would peck holes in trees and fish insects out with an elongated finger, among others.

Not that all of Dixon’s creations were dinosaurian reflections of familiar animals. Extrapolating from the tyrannosaur trend of evolving smaller and smaller arms, Dixon created the “Gourmand” — a carrion-eating descendant of T. rex that was little more than a mouth counterbalanced on two legs. Other sci-fi films have toyed around with similar ideas — like the archaic creatures that swarmed over Skull Island in the 2005 King Kong reboot — but Dixon’s work set the bar for speculative evolution.

Which is why I was a little bit disappointed when I saw The Good Dinosaur‘s scaly cast. Don’t get me wrong. I’m still excited for the movie and am eager to follow where director Peter Sohn leads us. But the diehard nerd in me was a little let down when I watched the first trailer and saw old-school dinosaurs instead of weird explorations of where evolution might go.

The prehistoric cast is pretty familiar. Arlo and his family are green sauropods fit to become the next Sinclair spokesaurians. There’s a four-legged snake of the sort that slithered around about 160 million years ago. Telltale two-pronged crests give away the 85 million year old pterosaur Nyctosaurus, and the film boasts some easily-recognisable Styracosaurus and Tyrannosaurus, too. The only ones I can’t quite place are the raptor-like bison-rustlers, although they happen to be the only dinosaurs appearing in the trailers to have any dinofuzz on them at all. (If any film company was going to introduce us to enfluffled dinosaurs, I was hoping it was going to be Pixar.)

There’s an evolutionary term for this — stasis. Paleontologists Niles Eldredge and Stephen Jay Gould invoked the term as a counterpoint to their notion of rapid, branching change called punctuated equilibrium. The basic idea is that once a new species becomes established, it will more or less stay the same until something comes along to create another evolutionary jolt.

The timeframe for stasis isn’t as long as The Good Dinosaur imagines, though. Even though T. rex was recognisable as T. rex for a span of about two million years, that’s about as good a record as any dinosaur species ever achieved. There’s no reason at all to expect that dinosaurs would persist for 66 million years or more with every tooth, scale, and feather in the same configuration. Consider all the weird fossil mammals that came and went during that time, like the shovel-tusked elephants, sabercats, bear dogs, and giant sloths, moulded by major changes such as the warming and cooling of the planet and the spread of grasslands where humid forests once grew.

Or, better yet, look at all the changes dinosaurs underwent during the 66 million years prior to their extinction. In the early days of the Cretaceous, about 135 million years ago, cousins of Allosaurus were apex predators while tyrannosaurs were fluffy pipsqueaks, horned dinosaurs were beaky little herbivores that ran around on two legs, and the armoured ankylosaurs were just started to proliferate to replace the recently-extinct stegosaurs. Basically, 66 million years is a long time for nothing to happen.

I get it from a filmmaking standpoint. We want to play with our favourite dinosaurs: Stegosaurus, Triceratops, Tyrannosaurus, and yes, even Brontosaurus. A world filled with strange new creatures might be too much of a shock for us to be comfortable going along on the journey. Rather than being a detailed reimagining of evolutionary what-ifs, The Good Dinosaur‘s opening conceit is just another variation of the many, many ways fiction has brought humans and dinosaurs into contact with each other. And this presents another evolutionary sticking point.

The usual image of a Mesozoic mammal is a shrew-like beastie snuffling around in the undergrowth, searching for worms while trying to stay out from under the clawed feet of giant dinosaurs. But that’s too narrow a picture of our ancient relatives. Paleontologists are recognising that, while small, mammals in the Age of Dinosaurs thrived. There were prehistoric equivalents to hedgehogs, anteaters, flying squirrels, beavers, and badgers, most belonging to totally extinct lineages but nevertheless pioneering the same ecological roles as their distant modern relatives. But primates weren’t among them.

Even though some molecular estimates put the origin of primates at about 85 million years ago, so far no one’s been able to find a Cretaceous protolemur or other primate progenitor. The closest thing is a little critter called Purgatorius, a little mammal that looked something like a tree shrew and may be related to primate-like mammals called plesiadapiforms that evolved and spread after the extinction of the dinosaurs.

And that’s just it. Even if primates were present during the days of Triceratops, they didn’t start to proliferate until the non-avian dinosaurs disappeared. Not to mention that it took another 60 million years before the first humans split off from the other apes, leaving a solitary species of hominin alive today. We’re an evolutionary fluke.

If we were able to rewind evolution and start it from the beginning, as Gould suggested in his book Wonderful Life, it’d be surprising if humans evolved again. We’re not inevitable, and certainly not an endpoint. Interactions large and small, from single cells subsuming each other to form more complex organisms to asteroids smacking the planet, have made life on Earth that we know a totally unique story out of many possibilities. And if we could do something as drastic as cancel a mass extinction, then the outcome would spin even further from the familiar. Undoing the extinction of Triceratops and its kin would erase the possibility of Homo sapiens ever evolving.

So, as a professional fossil fanatic, I can’t give The Good Dinosaur a scientific stamp of approval. But I’ll still be there on opening weekend, waiting to see dinosaurs run and roar across the screen. The western landscapes Pixar chose to set their new adventure are some of my own stomping grounds, and sometimes, as I’m hiking along, I try to imagine what it might be like if I were to stumble upon an Apatosaurus browsing from a pinon pine or a Ceratosaurus stalking off into the sunset.

Pixar put the effort in to make such visions real, and I think we could all use a little Mesozoic wish fulfillment now and then.