Want to know whether Anne Boleyn knew Utopia author Thomas More? There was a time when that answer would have involved painstakingly combing through historical archives hunting for arcane clues. But now you can search a massive online digitised database and get the answer in a fraction of the time.

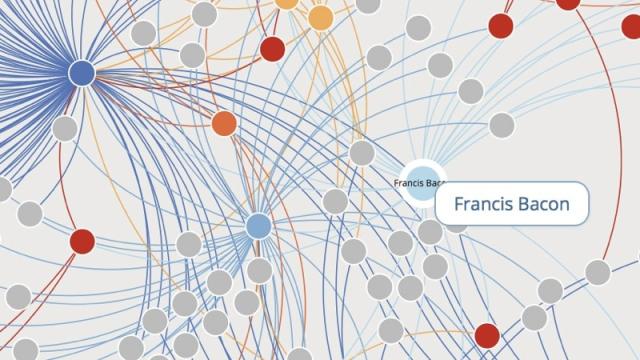

“Not only that, you can see all of the people they knew, thus giving you new ways to consider communities, factions influences and sources,” Christopher Warren, an English professor at Carnegie-Mellon University, said in a statement. He is project director for Six Degrees of Francis Bacon, a collaborative effort between CMU and Georgetown University that launched earlier this month.

It’s a play on the popular trivia game “Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon,” in which players try to make a series of connections to the actor based on those who have been associated in some way with his movies. Except in this case, it maps the social networks of historical figures from the 16th and 17th centuries.

The notion of six degrees of separation is a hallmark of the so-called small world phenomenon. While flawed, Stanley Milgram’s original 1967 study on social networks did offer intriguing evidence that smaller communities, such as actors, are densely connected by chains of personal or professional associations. Mathematicians even have their own version, the Erdos number, detailing how many steps a given mathematician is from Paul Erdos. Erdos is the Kevin Bacon of mathematics.

The distinguishing feature of any small-world network is having a lot of locally connected clusters, with a handful of critical long-range connections ensuring maximum efficiency when it comes to, say, transmitting information. As I wrote back in 2012:

The US airline industry’s network of flights is the quintessential small world network. Sure, we all like to moan about the inconvenience of connecting flights, but thanks to that small world organisation, we can usually get from any city to another within two flights — maybe three, for towns that are a bit more out of the way.

That’s because you have a lot of small local connections and a few major highly connected hubs providing those critical longer connections. In the end, your minimum path length is greatly reduced as a result. Imagine what a pain it would be if you had to hop from one local airport to the next to get from Los Angeles to New York.

And now Francis Bacon and his contemporaries have entered the small world social arena, thanks to the miracle of modern digitization. Daniel Shore, an English professor at Georgetown, and CMU’s Jessica Otis data-mined the entire Oxford Dictionary of National Biography — all 62 million words of that behemoth — and used it to map exactly who knew whom between 1500-1700.

The site uses handy colour-coding to help users spot connections. For instance, anyone whose nodes are red have the fewest social connections. But Warren points out that this doesn’t mean those people were hermits or something. Chances are, they just don’t show up much in historical records or scholarly articles. “Many women, for instance, appear in red,” he said.

More broadly, the CMU/Georgetown collaboration is part of a rapidly emerging field called digital humanities. As the co-creators said in a press release:

Six Degrees of Francis Bacon is an example of how digital humanists can use computers and technology to answer long-sought-after questions and explore fields like literature and history in new ways. It is unique because it encourages professional researchers, students and amateurs to participate in the same community. And, at a basic level, it can give anyone an immediate sense of historical networks and communities and help them develop more sophisticated interpretations.

By creating tagged and searchable digital archives of historical documents, it’s much easier for scholars to connect the dots between different records. “Once you digitize, you can get a birds-eye view that would have been impossible before,” Caroline Winterer, a historian at Stanford University, told New Scientist last year. “For the first time, we can begin to quantify the unknowns that historians routinely overlook.”

Winterer has used the digitised letters of Benjamin Franklin to map his social network, as part of Stanford’s Mapping the Republic of Letters. Other projects within the digital humanities include the analysis of archival records of London’s Old Bailey, transcripts of US congressional debates, and parliamentary records from the French Revolution during 1793’s Reign of Terror.

As for Six Degrees of Francis Bacon, Shore used the database in the classroom to demonstrate, for instance, that John Milton’s social circle wasn’t exclusively limited to other poets. Milton also knew composers and musicians, members of the clergy, educators, and even had a connect to science via his friendship with Henry Oldenburg, then secretary of the Royal Society.

“Every early modern document is a record of complex relations between authors, printers, publishers, booksellers, dedicatees, polemical opponents and so one,” said Shore. “Students can often add to the social network just by studying the relations documents in the title page and front matter of a single 16th century book.”

References:

Klingenstein, S., and Hitchcock, T., and Dedeo, S. (2014) “The civilizing process in London’s Old Bailey,” Proceedings of the National Academies of Science 111(26): 9419-9424.

Milgram, Stanley. “The Small World Problem,” Psychology Today, 1(1), May 1967, 60- 67.

Watts, Duncan J. and Strogatz, Steven H. (June 1998) “Collective dynamics of ‘small-world’ networks,” Nature 393 (6684): 440 — 442.

Winterer, Caroline. (2012) “Where is America in the Republic of Letters,” Modern Intellectual History 9(3): 596-623.

Image via Carnegie-Mellon University.